les Nouvelles August 2015 Article of the Month

Application Of Game Theory In A Patent Dispute Negotiation

Patent Images,

Chief Legal Officer,

Sydney, Australia

Introduction

Inventors will seek to protect the value of intellectual property (IP) they have created using a patent to prevent free-riding and unauthorised imitation. Patent filings worldwide grew 9.2 percent in 2012, representing the fastest growth recorded in the past 18 years.1 Firms are increasing their rate of patent filings because it raises their bargaining and retaliation power relative to competitors. This may lead to asymmetry of bargaining power between firms that are highly sophisticated in IP and those that are not. When asymmetry exists, a firm with a stronger patent position can intimidate weaker firms.

Patent disputes arise between a patent owner and an infringer when a patent is alleged to have been infringed. The patent filing trend is reflected in the increasing number of patent disputes. In the U.S., it has grown by almost 30 percent in 2012.2

Patent disputes are resolved by: trial, pre-trial summary judgment or settlement. Over 80 percent are settled.3 Selecting a negotiation strategy to settle patent disputes is an important consideration for both the patent owner and alleged infringer to achieve favourable outcomes. Interaction between them early in the dispute and negotiation affects the terms of the settlement.

This paper focuses on patent disputes involving practising entities in an oligopoly that both possess sizable patent portfolios with roughly similar value. Practising entities are firms that have the capability to invent, design, manufacture, or distribute products with features protected by a patent. This paper discusses a strategic approach based on game theory for negotiating the settlement of a patent dispute that achieves favourable outcomes for oligopolists.

Batna/Watna Analysis

A Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) is a payoff4 for a firm/player received from one of their alternatives if the negotiation fails to reach an agreement.5 Alternatives to a negotiated settlement for a plaintiff include: litigation, self-help and avoidance.

Self-help includes generating bad publicity about the opponent not respecting IP rights. This insinuates that others should not respect the opponent’s IP rights. This can be communicated to the opponent’s suppliers, distributors and customers. Self-help involves a low cost but does not provide certainty of a particular outcome since the dispute is not resolved. Therefore, risks include unrestrained infringement and losing credibility which signals to other market participants that imitation will be tolerated.

Avoidance acknowledges the existence of an unquantified level of patent infringement, and maintains the status quo. As an analogy, the U.S. spent 7 percent and the Soviet Union spent 14 percent of their respective GDPs at the height of the Cold War on military expenditure.6 Avoidance of a Hot War superficially appears to involve a low cost with lower risks, but there is a large hidden cost of maintaining the status quo, including opportunity cost. For oligopolists, the hidden costs include stockpiling of patents, close monitoring of each other’s patent portfolio, and frequently obtaining legal opinions. Avoidance produces a similar uncertain outcome resulting in the same risks as self-help. If avoidance is not selected, its hidden cost could be more productively used.7 After the Cold War ended, the U.S. spent 2.9 percent and Russia spent 3.4 percent on military expenditure at its lowest level in 1999,8 and these cost savings were available for other government expenditure such as welfare and education.

Patent litigation is the most resource intensive9 alternative for both players but will ultimately lead to a decisive outcome. The use of this alternative may be threatened to change the nature of a patent dispute10 if the threat is credible. The BATNA/WATNA analysis for patent litigation can be found at http://www.jameswanpatent.com/negotiation.html.

Beyond defending the suit, the defendant can retaliate by filing suit against the plaintiff if their patents have been infringed. This counter litigation is an example of a Tit-For-Tat (TFT) strategy. The TFT strategy may form an escalation cycle between the players raising the stakes to a catastrophic level. The defendant also has non-litigious alternatives.11

Types of Negotiated Settlement

Patent disputes are settled by one or a combination of: one-time payment for past infringement, royalty payments for future use, an anti-cloning provision to prevent verbatim copying of products, and crosslicensing of patents.12 If court proceedings are filed, settlements occur early thereafter.13 The probability of settlement is influenced by certain factors.14

Settlement offers are used as signalling devices to indicate the bargaining strength of the player making the offer. If there is a large difference in the bargaining strengths15 of the players, then frequently the weaker player will be more cooperative to avoid litigation.16

In an oligopoly, settlement prior to litigation between oligopolists will be scrutinised to determine if they are anti-competitive.17 Therefore, patent litigation should be threatened or initiated because:

- It negates any allegation of collusive behaviour; and

- The value of a patent license flows from the threat of litigation.18

Terms of Settlement

If the defendant has a weak or non-existent patent portfolio, the plaintiff may choose to offer a license rather than pursue litigation. Licensing with a high royalty rate may achieve the plaintiff’s desired outcome.19 It also avoids litigation costs and avoids exposing their patents to invalidity challenge. After a defendant agrees to a license, they may eventually leave the market of their own volition because of insufficient profit. This scenario can be less costly for the plaintiff than using litigation to achieve a decisive win.20

If the defendant has a strong patent portfolio, patent cross-licensing is an option which is more likely between players which invest in R&D, have a comprehensive patent filing strategy, and have amassed a substantial patent portfolio in their industry.21 There is economic value in eliminating uncertainty because it manages present risk and hedges future bets. Cross-licensing neutralises the use of licensed patents in future patent disputes between the players, and eliminates the need for players to check for cheating.22 Cross-licensing may be more valuable than royalty payments.23 These benefits make cross-licensing attractive to rational oligopolists in the early stages of a patent dispute. However, there are risks for a plaintiff when it crosslicenses including:

- Losing credibility if the plaintiff never enforces their patents in public;

- A risk of declaratory judgment action;

- Establishing royalty or cap damages if future defendants refuse to cross-license and patent litigation proceeds; and

- Jeopardising the ability to seek injunctions in the future.

Game Theory for Patent Enforcement Strategies and to Resolve Patent Disputes

Game theory provides a tool for analysing the behaviour and decision-making process of rational players and permits one to optimally resolve a conflict or to form a strategy based on one’s knowledge of a situation, the choice of outcomes among alternatives, and the desirable amount of risk.24 Game theory is useful to demonstrate the evolution of cooperative behaviour when negotiating a patent dispute since strategic interaction between players affects the decisions they make. If oligopolists are involved, strong interdependence among them results in strategic behaviour.

There are three basic elements of a game: players, moves/actions, and payoffs. These elements and the strategies that determine what moves each player will make for a particular situation in a patent dispute are discussed.

Players

Patent disputes involve multiple players. In an oligopoly, players include oligopolists and smaller players. The patentee is more likely an oligopolist, and the defendant could be an oligopolist or a smaller player. Players not directly involved in the dispute will observe changes to the patent landscape. Therefore, patent disputes are not dyadic, but rather a larger N-person game exists (more than two players).

In game theory, all players should be considered rational which means they always choose a strategy that gives the highest expected utility. However, the appearance of irrationality can make a player’s threats credible.25 It is reasonable to expect that rational players know that filing patent infringement lawsuits is not a better use of money than developing new products for customers26 or increasing sales and marketing spend.

Moves

Moves are actions taken by the players at some point during the patent dispute. A move may be unconditional or conditional. The nature of a patent dispute can also be changed using commitment,27 threats,28 and promises.29 These conditional moves can change certain moves from simultaneous to sequential which may generate first mover advantage30 for a particular tactic. In a patent dispute, each player may have a limited number of available moves at any given point, and not all moves are available to both players. Moves can be characterised as cooperative when they de-escalate tension and lead towards settlement, or combative when they escalate tension and lead closer towards a court judgement.

In a patent dispute there are both simultaneous and sequential moves. It is not solely a sequential move game because there are actions for the players to perform independent of the actions of another player.31 These simultaneous moves may be repeated.

There are four stages in the litigation path in a patent dispute,32 each involving critical uncertain events.33 To solve a game with sequential moves requires the use of backwards induction and game trees/decision trees, perfect information and strategies that are irreversible.34 A patent dispute lacks perfect information despite the discovery process because neither player knows the resistance point of their opponent or true value of a patent.

To solve a game with simultaneous moves requires construction of a payoff matrix for each possible strategy. Each player needs to identify whether they have a dominant strategy, and if so, use it. For example, patent litigation is a dominant strategy for an oligopolist against a weaker player.35 The weaker player has no dominant strategy.36 In the absence of a dominant strategy, dominated strategies should be eliminated from consideration, successively. After all dominated strategies have been discarded, the Nash Equilibrium of the game should be identified. The Nash Equilibrium is where each player does its best given the action of the opponent. It is a pair of strategies that are best responses to one another. The Nash Equilibrium does not necessarily lead to the best outcomes for one, or even both, players.

The minimax theorem37 can be used to find the Nash Equilibrium for simultaneous move games. The minimax theorem is applied by the maximin strategy and minimax strategy. A maximin strategy is where your minimum payoff is highest. It is a low risk/ cautious strategy and achieves the best expected payoff you can possibly assure yourself. It is the mixture that yields a player his best worst-case expectation. A minimax strategy limits the opponent’s minimax value (their best expected payoff), and thus the maximum advantage of the opponent is minimized.

A patent dispute can be solved by combining decision trees and the payoff matrix, and combining rollback and Nash Equilibrium analysis in appropriate ways. Also, the maximin strategy38 should be used because a patent dispute is an N-person game meaning the best choice for a player is to select a cautious strategy.39 Therefore, each player should at least strengthen its BATNA as that is low risk. A plaintiff can strengthen their BATNA by filing more patents, investing more resources in generating more valuable patents (stronger/valid and broader scope) to increase their bargaining power should a patent dispute arise. A defendant can strengthen their BATNA by doing the same as the plaintiff to increase opportunities for counter litigation as a defence. In addition, a defendant should find prior art to weaken or invalidate the plaintiff’s patents if they are asserted, and consciously design products that are clearly beyond the scope of the plaintiff’s claims.

First Mover Advantage

Making the first move is advantageous in a patent dispute negotiation because it gives the player an opportunity to frame the negotiation, influence others, communicate the sequence that issues are to be negotiated and establish precedence.40

When a patentee chooses to litigate, the patent is vulnerable to invalidation. This has been argued as indicating symmetry between the players’ bargaining positions and will motivate the players to settle the lawsuit close to its expected value.41 This symmetry is illusory because the patentee:

- Has the power to decide against which player to assert their patent;

- Has the power to decide the quantity and specific patents to assert;

- Has the power to discontinue the litigation process at almost any point;

- Incurs a relatively small cost to file a patent, but the defendant carries the burden of proof that the patent is invalid which is costly;

- Is not punished for discontinuing litigation other than paying some of the litigation costs of the defendant; and

- Often has a much lower litigation cost than the defendant since most patent litigation cases end in an agreement out of court.

A patentee enjoys an inherent first mover advantage.

Payoffs

Payoffs are numbers which represent the motivation of the players. Different moves42 result in different payoffs. The payoff of one player depends on their strategy and also the strategies of the opponent. The most successful player maximises their payoff.43

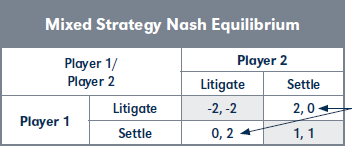

In a patent dispute, payoffs preferably are ordinal which rank the desirability of certain outcomes. Using cardinal values is difficult due to complexities and unknowns including: amount of damages to be awarded,44 legal expense,45 acceptable royalty rates for particular industries (varies from 20 percent to 60 percent of operating profit),46 etc. A simple payoff matrix in normal-form for a patent dispute based on the Hawk-Dove game:

For a settlement (original benefit = 1) to become acceptable for oligopolists, its terms need to generate a payoff greater than winning at litigation (original benefit = 2) by incorporating cross-licensing in addition to monetary payments (possible new benefit ≥ 3). Payoffs change over time: values are higher earlier on because money received earlier is worth more; and values are lower in the future because money received later is worth less, and expenses accumulate over time.

Characterising the Type of Game for a Patent Dispute

Game Symmetry

A game can be symmetric in its structure or in its payoffs. Each player in a patent dispute has a different number of choices from the other,47 and will receive different payoffs for the same actions.48

Zero Sum or Non-Zero Sum Game?

A patent dispute is a non-zero sum game because the loss to a defendant is potentially larger than the gains to the plaintiff49 thus there is no single optimal strategy that is preferable to all others, nor is there a predictable outcome.50 Patent disputes involve decision making51 and self-interest (both competitive/ opposed interests and cooperative/complementary interests). Opposed interests include exclusivity and freedom to operate. Complementary interests may include avoiding a price war, increasing the overall size of the market, and preventing free riding of their intellectual property by others that do not invest in R&D. Each decision involves evaluating risk and the likely rewards if selected or discarded.

A patent dispute may be a positive-sum game if cross-licensing forms part of the settlement. However, it is likely the plaintiff will achieve a greater payoff that includes a monetary payment and/or a license to a greater number of highly valuable patents of the defendant.52

Which Known Non-Zero Sum Game Does a Patent Dispute Resemble?

Previous papers have suggested that a patent dispute is an Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma game.53 However, a patent dispute is distinguishable from this game and also the Chicken game54 because verbal/written communication between the players is permitted, some moves are sequential and the players can move more than once.

A patent dispute closely resembles the Hawk-Dove game55 because the players compete in the same market, neither want to back down but neither wants to continue to the death,56 and there are asymmetric costs because combative interaction by a Hawk has a higher cost than a cooperative interaction by a Dove avoiding combat.57 The Hawk-Dove game has three Nash Equilibria: two are pure strategies: (combat, combat) and (cooperate, cooperate), and there is one mixed strategy equilibrium. The mixed strategy Nash Equilibrium is (combat, cooperate) or (cooperate, combat) and functions as a self-enforcing agreement. The mixed strategy Nash Equilibrium is useful to predict what rational players would do. Players often succeed in cooperating with one another and avoiding equilibrium play.58 The Nash Equilibrium makes clear that because the (cooperate, cooperate) outcome is a result of a pure strategy and not a mixed strategy Nash Equilibrium, it is going to be unstable in ways that can make cooperation difficult to maintain.59 Therefore the use of cooperative-reciprocal strategies to build, strengthen and maintain cooperation is necessary in negotiating the patent dispute.

Multiple interactions means a patent dispute is an iterated Hawk-Dove game.60 Each interaction is costly because resources (time and money) are required to some degree for each combative and cooperative move. Avoidance may appear cooperative but results in a resource wasting standoff without benefit as discussed earlier in the BATNA/WATNA analysis section. If the players are oligopolists, there is a risk that repeated combative interactions can escalate in intensity leading to mutual destruction.

Strategies

Strategy Definition

A strategy is a future oriented solution to achieve a desired outcome where there is some uncertainty.61 The strategy is pursued by tactics comprising moves. Positive tactical outcomes may ultimately achieve the desired outcome.

Strategic Outcomes

A desired outcome for an oligopolist is to maintain/ increase market power and improve profitability. A smaller player differs because lower profitability is acceptable to initially build market share. A first player may harm a second player’s ability to achieve its desired outcome by introducing a similar lower priced product that the second player provides. In this scenario:

| First Player | Second Player |

| Defendant | Plaintiff |

| Oligopolist or Smaller Player | Oligopolist |

If inexpensive non-litigious tactics are unsuccessful in curtailing the defendant’s harm, the plaintiff will consider initiating a patent dispute. Patent litigation or licensing are tactics for achieving the desired strategic outcome of the plaintiff to maintain its market share62 or increase its profitability63 through positive tactical outcomes. The tactical outcomes include:

- Forcing the defendant to design around the scope of the patent(s) and incur a higher cost of production through inefficiency or lower sales from reverting to technologically inferior products;

- Causing the defendant to be less profitable by forcing it to pay a royalty, or become less competitive by having to raise its price by the royalty amount;

- Jeopardising the defendant’s solvency if the plaintiff wins in court and is awarded punitive damages together with injunctive relief; and/or

- Allowing the plaintiff access to new markets and exclusive third party technology via crosslicensing of the defendant’s highly valuable patents.

Brinkmanship

Brinkmanship is a risk strategy used to achieve the highest possible outcome, where the frequency of cooperative interactions is low. It is the main idea behind the Hawk-Dove game which is to bring the situation to the edge of a disaster (taking an issue to the limit or brink). In a patent dispute, refusing to agree on a settlement until immediately prior to the court judgement is brinkmanship. Although settlement can reduce the risk to zero and end the brinkmanship, the probability of settlement will vary depending on circumstances.64

Brinkmanship involves increasing the risk of reaching an adverse court judgement to induce one player to compromise. The judge or jury function as the element beyond the control of the parties, which is required to make brinkmanship effective. Also, there must be a credible threat. To make the threat credible: (i) change a small chance of a large loss to a large chance/ certainty of a small loss that increases over time; or (ii) reduce the impact of a threat or make it more specific/targeted to elevate the risk in small steps. The player that fears the brink less is in a stronger bargaining position and is more willing to elevate the risk exposure. As conflict escalates, the probability of the Court judgement will be sufficiently high that one side may want to back down because the plaintiff may be worried that its patents are found invalid, or the defendant may be worried that the asserted patents are valid and infringed and found liable for punitive damages.

The bargaining power of a player is weaker if only two actions are available: (i) settle or (ii) go to the ultimate threat point which is litigation until court judgement. The bargaining power of the player is stronger if it uses credible, probabilistic threats. For example, a probabilistic threat is an observable action that leads towards a Court judgement65 such as commencing an ITC Action or proceeding to a pre-trial hearing such as a Markman hearing. A probabilistic threat demonstrates a commitment to action.

Cooperation

With the threat of punishment, a mutually cooperative strategy is superior66 to one that is combative. The reason why is called the backward induction paradox. Backward induction is a reasoning process by which the players working backwards from the last possible move in a game, and anticipate each other’s rational choices. Establishing early cooperation between oligopolists in a patent dispute based on rationality and reciprocity gains important benefits. These benefits are: avoiding many interactions with the Nash Equilibrium of (combat, combat) because that always results in the worst payoff for both in a patent dispute; cross-licensing of patents for earlier access to new markets rather than waiting for patents to expire; reducing legal expenditure which can be redirected to more productive business activities; and delaying or denying new entrants a clear opportunity to exploit technologies if the oligopolists’ patents avoid being declared invalid.

Failure to cooperate early is detrimental because it results in: increasing legal costs, delay, loss of manpower, prolonged legal uncertainty and a lingering risk that the patents will be invalidated or that punitive damages may be awarded. To build cooperation early:

- Create reasonable expectations of future interaction which increase the chance of retribution.67

- Publicise cooperative behaviour you want imitated.68

- Build interdependence by forging a group identity to create a cooperative environment.69

Factors essential to cooperation include: ensuring continuity (inherent because a patent dispute is an iterated game), and changing the payoffs of cooperation and combat. Payoffs can be changed by increasing the number of patents to be cross-licensed above what is asserted in a patent dispute. Cooperation can also evolve through three general strategies based on reciprocity (i.e. cooperative-reciprocal strategies):

- TFT strategy:70 cooperate first and then do whatever your opponent does.

- Win-Stay, Lose Shift (Pavlov strategy):71 repeat your behaviour from the last round if it was successful,72 but change your behaviour if you lost in the last round.73

- Zero Determinant strategy (ZD):74 extort an opponent such that the only way they can maximise their payoff is to give you an even higher payoff.

Pure Strategy or Mixed Strategy for Resolving Patent Disputes

A pure strategy for resolving a patent dispute is not available because there is no constant behaviour for all interactions that is always stable, and always optimal. It is not always best to be combative. If every player is combative, they are wasting resources battling each other, and getting injured to some degree each time. The more cooperative players may eventually perform better because they do not unnecessarily waste resources fighting and avoid injury.

Strategies are considered mixed if the behaviour expressed is conditional on the players involved. For a patent dispute, a mixture of combative and cooperative behaviour is preferred and is the most plausible75 compared to pure strategies. Each player mixes its strategies by cooperating sometimes while not cooperating (being combative) at other times. Since the players are adversarial, the mixing is not coordinated between the players and appears random from the perspective of the opponent. A mixed strategy may also refer to a combination of distributive and integrative negotiation tactics in some proportion to address the competitive and cooperative elements of a patent dispute.

Some literature on negotiation theory states that in the context of a dispute, the type of negotiation is more likely to be a distributive process because the sole issue is a claim for damages. In contrast, a patent dispute has more than one issue and many options to fully resolve the dispute by way of negotiated settlement as described earlier. These complexities integrate both players’ complementary interests to create value. One particular mutual interest may arise for oligopolists if they perceive themselves as innovators and new entrants as free riding imitators who make little or no R&D investment.

An integrative process for negotiating the patent dispute is a cooperative approach and should be explored before commencing a distributive process. When there is simultaneous bargaining over multiple issues in a cross-licensing negotiation, there is a different value perceived by each player on each of these issues. The differences in their perception should be exploited to obtain a better outcome for both players.

A mixed strategy may be size or bargaining power related, for example, cooperate with stronger players and attack weaker players. A mixed strategy may be related to the value/quality of the benefit. The percentage76 of time a player should be combative is proportional to Benefit÷Cost. If the ratio is low, it is better not to escalate conflicts and be cooperative. A high ratio favours being combative. Combat is only rational if the reward for combative behaviour outweighs the risk and cost of combat. Low quality resources77 are unlikely to drive intense combat. The most intense conflicts occur between players of equal size fighting for high quality/high value resources.78 Both players may sustain injuries that are difficult to recover from.

Combat may be avoided when players demonstrate their superiority.79 However, escalation may occur between evenly matched players or if the seemingly weaker player continues their aggression despite a demonstration of superiority by the opponent. Nevertheless, it is unlikely for players to persistently risk injury in situations where combat would produce a negative expected payoff.80

Three mixed strategies for resolving patent disputes corresponding to known strategies for the iterated Hawk-Dove game81 are:

Retaliator strategy: cooperate first, but escalate to combat if the opponent does.82

Bully strategy: combat first and continue combat, but retreat (cooperate) against combat by the opponent, then revert to Retaliator strategy.83

Bourgeois strategy: combat if your patents are infringed, retreat if you infringe the opponent’s patents.84

The choice between which of the first two strategies to use will depend on the relative bargaining and retaliation power of the players. A player that does not have a significantly stronger bargaining power than its opponent should choose the retaliator strategy.

Benefits of Using a Mixed Strategy for Patent Disputes

Players are unlikely to know the true value of size asymmetries or value the strength of their patents in exactly the same way.85 Players gain more information by participating in patent disputes so they can update their asymmetry estimates.86 Consequently, it is beneficial for an oligopolist to first assert their patents against a weaker player. The weaker player has a lower probability of successfully invalidating the patents because they lack resources, sophistication, experience, and deep knowledge about the prior art. After winning against the weaker player, the oligopolist can assert these litigated patents against an oligopolist opponent with a higher confidence of their validity. This is a divide-and-conquer strategy to defeat a preselected group of defendants sequentially. It changes the form of game from one that could be simultaneous move, to sequential move.

In the U.S., a patent is declared invalid by a court only if there is “clear and convincing” evidence.87 Surviving a challenge to the patent’s validity makes it stronger. In some countries a Certificate of Validity is issued when validity has been unsuccessfully challenged.88 Litigated patents are therefore more valuable than non-litigated patents.89 A mixed strategy can minimise the plaintiff’s risk when seeking to improve the value and strength of their patent portfolio.

Effectiveness of Strategies

A Successful Strategy

Success should be measured relatively rather than in absolute performance to determine whether the desired outcome was achieved.90 Although a court will determine a winner, it may be a Pyrrhic victory especially for oligopolists. The damages awarded may not cover legal expenses and thus the plaintiff is worse off than if it had done nothing. Injunctive relief may prove worthless if the opponent or market has obsoleted the infringing products and the sales the infringing products are low to non-existent. Superior strategies can defend against noncooperative players and exploit the advantages of mutual cooperation with cooperative players.91 Superior strategies have four key attributes: (i) cooperation,92 (ii) retaliation/retribution,93 (iii) forgiveness and generosity, and (iv) clarity/consistency.94

Effectiveness of Brinkmanship

Brinkmanship is successful if the opponent compromises. Ending up in court or reaching a court judgement indicates failed brinkmanship because the opponent did not back down earlier. The worst case95 documented in the U.S. was 10 years of patent litigation together with $1 billion in damages awarded to the patent owner. That is the extreme example, as the annual median damages award is approximately $4.9 million.96 In a patent dispute, an agreement usually cannot be reached until some injury has already been done and this is not solely indicative of failed brinkmanship. Some inflicted injury makes the threat more credible.

Effectiveness of Cooperative-Reciprocal Strategies

Some players may cooperate at the beginning of patent litigation, however, there is a risk that their interactions will degenerate to an equilibrium of combat as soon as one player acts, or is perceived to act contentiously. This is the grim trigger strategy where moves are cooperative until the opponent makes a non-cooperative move which you retaliate by being non-cooperative on all successive moves. A disciplined use of cooperative-reciprocal strategies may reduce the risk the occurrence of or allow recovery from a grim trigger strategy. In addition, superior strategies must account for choices made in error. Most games operate in noisy conditions where the opponent does not necessarily know whether a given action is an error or a deliberate choice, and a single error can lead to significant complications. There are three different approaches to coping with an error:97

- Generous TFT strategy–allow 10 percent of the opponent’s non-cooperation to go unpunished;

- Contrite TFT strategy–avoid responding to the opponent ‘s non-cooperation after its own unintended combat;98 and

- Pavlov strategy.

Pavlov strategy is more successful than TFT based strategies in achieving more favourable outcomes for both players from increased cooperation because it bases behaviour on previous payoffs rather than the opponent’s previous move.99 Also, Pavlov strategy is fairly tolerant and can correct errors.

Effectiveness of Mixed Strategy

An oligopolist using a mixed strategy can efficiently allocate its resources depending on the opponent and the value/quality of the benefit. It also manages their risk to a desired amount, makes their moves appear random to the opponent and other players in market, and maximises their payoff. Randomness avoids others from accurately predicting your next move.

Effectiveness of Cross-Licensing Between Oligopolists

The cross-licensing of patents in a negotiated settlement is an optimal outcome with long term benefits. Using the Cold War analogy again, the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) for nuclear disarmament between the Soviet Union and the U.S. in 1991 reduced the total number of nuclear warheads by more than 50 percent which lowered the long term cost of maintaining their respective nuclear arsenals. By cross-licensing a significant proportion of their patent portfolios, oligopolists can redirect their effort on innovation and value creation for their customers rather than anticipating and preparing for possible patent disputes occurring between each other. For oligopolists, cross-licensing can produce a better outcome than avoidance or protracted patent litigation.100

Example—Apple Inc v. Samsung Electronics Co Ltd.

The market structure for the smartphone industry is an oligopoly because the five largest players have 75 percent of the global market share.101 The smartphone industry resembles an N-person game because apart from phone manufacturers there are other players such as mobile phone operating system vendors (e.g. Android). Google, the developer of Android, offered to help fund Samsung’s legal costs and damages.

In 2010, Apple held 16 percent of the global smartphone market and Samsung held 4 percent,102 both considered oligopolists. One of Apple’s strategic outcomes is to maintain or increase its market power in the smartphone market and viewed the introduction of Samsung’s Galaxy S smart phone in March 2010 as a threat to achieving that strategic outcome. Apple’s fear was justified because by July 2013, Samsung held 33.1 percent and Apple held 13.6 percent market share.103 For Samsung, its strategic outcome was “beating Apple.”104 In 2010, both parties each had over 500 patents in the U.S.,105 which are generally considered strong patent positions.

Apple warned Samsung as early as 4 August 2010 that it believed it was infringing on Apple patents relating to the iPhone,106 and indicated Samsung should request a license. On 5 October 2010, Apple offered to license its portfolio of patents to Samsung provided it would pay $30 per unit, with a 20 percent discount if Samsung cross-licensed its patent portfolio back to Apple.107 This equated to $250 million in royalties to Apple for 2010. Samsung declined the license. For Apple, the BATNAs of self-help and avoidance were not strong. Therefore, chose litigation and moved the first move.

On 15 April 2011, Apple filed suit against Samsung. The trial commenced on 30 July 2012108 which indicates failed brinkmanship because both parties ended up in court and proceeded until court judgement on 24 August 2012. Apple was awarded $1.05 billion in damages.109 Since 2011, both parties have used a TFT strategy suing and countersuing each other in multiple countries to force the other party to back down. Only the retaliator strategy of the three mixed strategies for resolving patent disputes in this iterated Hawk-Dove game has been used, and because litigation is ongoing there remains a risk that repeated combative interactions can escalate in intensity leading to mutual destruction allow others to increase their share of the market at Apple and Samsung’s expense.110

More than 4 years have passed since the dispute arose, and although the court has determined Apple as the net winner, it is substantially a Pyrrhic victory. Legal expenses incurred are likely to have exceeded $60 million111 for each party to date, the smartphones of 2010 to 2012 have been obsoleted, and some of the patents asserted are no longer relevant for newer products. It is not publicly known why Samsung declined Apple’s offer, or whether it counter offered with a lower royalty rate or a higher discount to be applied for cross-licensing its patents. Ideally, this should have been negotiated upon between October 2010 and April 2011, but it appears that negotiation, if any, was short lived since Apple commenced litigation within 6 months. It would have been to Samsung’s benefit to prolong negotiation as long as possible while it continued to increase market share.

In this patent dispute, a more favourable outcome for Samsung would have been to pay less than $30 per unit for 2010, save $60 million in legal expenses, and accept Google’s assistance. Samsung later could challenge the validity of Apple’s patents asserted against it via re-examination at the USPTO. Samsung could also design new phones that were beyond the scope of any remaining valid patents to avoid future royalty payments. Ultimately, Apple did not achieve its desired outcome since all permanent injunctions against Samsung were overturned which allowed Samsung to achieve its desired outcome of surpassing Apple’s market share by 2.4 times as at 2014. Although Apple was awarded damages, this amount decreased after appeals, from originally $1.05 billion112 down to $600 million,113 then back up to $890 million.114 The final amount is slightly less than if Samsung had paid $250 million each year to Apple, multiplied by 4 years since the dispute first arose.

Conclusion

In an oligopolistic market, an oligopolist that uses a combination of brinkmanship, cooperative-reciprocal strategies and a mixed strategy to resolve patent disputes can achieve the best outcome against other oligopolists and small players. Additionally, cross-licensing is an important element to resolve patent disputes between oligopolists that is likely to produce favourable outcomes if negotiated on earlier in the patent dispute.

Bibliography

"2013 Edition Of The World Intellectual Property Indicators," (9 December 2013), WIPO. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/wipi/. [26 May 2014].

Alberto Galasso, "Broad Cross-License Agreements and Persuasive Patent Litigation: Theory and Evidence from the Semiconductor Industry," (July 2007), EI, 45. Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin, "From Extortion To Generosity, Evolution In The Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma," (July 2013), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110: 15348- 15353.

AlixPartners, "Bargaining Power in a Licensing Negotiation: Application of Game Theory," (2011).

American Intellectual Property Law Association, "Report Of The Economy Survey," (2013).

Avinash K. Dixit and Barry J. Nalebuff, "Thinking Strategically," (17 April 1993), W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 9780393069792.

Bengt Carlsson and Stefan Johansson, "An Iterated Hawk-and-Dove Game," (1997), ISBN:3-540-64769-4.

Bruce L. Hay and Kathryn E. Spier, "Litigation And Settlement," (1998), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics and the Law, page 6.

Bryan D. Jones, "Reconceiving Decision-Making in Democratic Politics," (1994), University of Chicago Press.

Charles A. Holt and Alvin E. Roth, "The Nash Equilibrium: A Perspective," (2004), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 101, 12, March 23 2004, 3999-4002.

Charles C. Cowden, "Game Theory, Evolutionary Stable Strategies And The Evolution Of Biological Interactions," 2012, Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):6.

Chris J. Katopis, "Perfect Happiness?: Game Theory As A Tool For Enhancing Patent Quality," (2008), YaleJournal of Law and Technology: Vol. 10, Article 9.

Claude Crampes and Corinne Langinier, "Litigation And Settlement In Patent Infringement Cases," (July 2001), RANDJournal of Economics, Vol. 33(2), pages 258-274.

Colleen Chien, "From Arms Race To Marketplace: The Complex Patent Ecosystem And Its Implications For The Patent System," (January 2010), Santa ClaraLawReview,Articles 121—150.

Corina E. Tarnity, Tibor Antal and Martin A. Nowak, "Mutation-Selection Equilibrium In Games With Mixed Strategies," (29 July 2009), Journal of Theoretical Biology, 261 (2009) 50–57.

Douglas Fox and Roy Weinstein, "Arbitration And Intellectual Property Disputes," (April 2012), AmericanBar Association 14th Annual Spring Conference, Washington D.C.

Douglas Fox and Roy Weinstein, "Myth Busting: Arbitration Perceptions, Realities And Ramifications," (19 April 2012), American Bar Association 14th AnnualSpring Conference, Washington, D.C.

Elias G. Carayannis and Jeffrey Alexander, "The Wealth Of Knowledge: Converting Intellectual Property To Intellectual Capital In Co-Opetitive Research And Technology Management Settings," 1999, InternationalJournal of Technology Management, Volume 18 (3-4), page 27.

Francesca Flamini, "A Non-Technical Analysis Of Long-Run Dynamic Negotiations," (2007), Working Papers 2007_23, Business School—Economics, University of Glasgow.

Gideon Parchomovsky and Alex Stein, "Intellectual Property Defences," (October 2013), Columbia LawReview,Vol. 113, 2013, pp. 1483-1542.

Gina A. Kuhlman, "Alliances for the Future: Cultivating a Cooperative Environment for Biotech Success," (February 2014), Berkeley Technology LawJournal, Volume 11, Issue 2, Article 3.

J. Maynard Smith & G. R. Price, "The Logic of Animal Conflict," (November 1973), Nature 246, 15–18.

James L. True, "Arming America: Attention And Inertia In U.S. National Security Spending." Available from: < http://dept.lamar.edu/polisci/TRUE/True_art_tlp.html>. [26 May 2014].

Jasvir K. Grewal, Cameron L. Hall, Mason A. Porter and Marian S. Dawkins, "Formation of Dominance Relationships via Strategy Updating in an Asymmetric Hawk-Dove Game," (27 August 2013). Available from: <http://io43.com/pdf/1308.5358.pdf>. [26 May 2014].

Jasvir Kaur Grewal, "Cooperation versus Dominance

Hierarchies in Animal Groups," (September 2012), Oriel College, University of Oxford.

Jay P. Kesan and Gwendolyn G. Ball, "How are Patent Cases Resolved? An Empirical Examination of the Adjudication and Settlement of Patent Disputes," (2006), WashingtonUniversity Law Review, Vol. 84, No. 2, pp. 237-312.

Jay Pil Choi, "Patent Litigation as an Information Transmission Mechanism," (December 1998), TheAmerican Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 5.

Jean Lanjouw and Mark Schankerman, "Enforcing Intellectual Property Rights," (December 2001), ISSN 0969-4447.

Jean Lanjouw and Mark Schankerman, "Protecting Intellectual Property Rights: Are Small Firms Handicapped?," (2004), Journal of Law and Economics.

Jennifer Golbeck, "Evolving Strategies for the Prisoner’s Dilemma," (February 2002), Advancesin Intelligent Systems, Fuzzy Systems, pp. 299-306. Available from: <https://www.cs.umd.edu/~golbeck/downloads/JGolbeck_prison.pdf> [26 May 2014].

Jeremy W. Bock, "Neutral Litigants in Patent Cases," (2 January 2014), North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology, Volume 15, Issue 2.

Jianzhong Wu and Robert Axelrod, "How To Cope With Noise In The Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma," (March 1995), TheJournalofConfl Resolution, Vol. 39, Issue 1, pp. 183-189.

Joe C. Magee, Adam D. Galinsky and Deborah

H. Gruenfeld, "Power, Propensity to Negotiate, and Moving FIrst," (2007), Personalityand Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 200-212.

John R. Allison, Mark A. Lemley and Joshua Walker, "Extreme Value or Trolls on Top?," (December 2009), UniversityofPennsylvaniaLaw Review, Vol. 158, No. 1.

Jonathan E. Kemmerer and Jiaqing Lu, "Profitability And Royalty Rates Across Industries: Some Preliminary Evidence," (2008), Journal of the Academy of Businessand Economics, Chart 2.

Joseph Farrell and Robert P. Merges, "Incentives to Challenge and Defend Patents: Why Litigation Won’t Reliably Fix Patent Office Errors and Why Administrative Patent Review Might Help," (2004), 19 Berkeley Tech L. J. 943, 948-52.

Kevin Mitchell and James Ryan, "Game Theory Models Of Animal Behaviour," (2003), COMAP, Inc. Available from: <http://www.cengage.com/math/book_content/0495011592_giordano/student_cd/ilaps/game_theory.pdf> [26 May 2014].

Kimberlee G. Weatherall and Paul H. Jensen, "An Empirical Investigation into Patent Enforcement in Australian Courts," (May 2005), FederalLawReview, Volume 32.

Martin Nowak and Kari Sigmund, "A Strategy of Win- Stay, Lose-Shift that Outperforms Tit-For-Tat in the Prisoner’s Dilemma Game," (1 July 1993), Nature, Vol. 364, pp. 56-58.

Michael J. Meurer, "The Settlement of Patent Litigation," (1989), TheRANDJournalofEconomics, Vol. 20, No. 1.

Michael J. Meurer, "Controlling Opportunistic And Anti-Competitive Intellectual Property Litigation," 2003, Boston College Law Review, 44(2): 509–44.

Michael Schwarz and Konstantin Sonin, "A Theory Of Brinkmanship, Conflicts, And Commitments," (20 December 2004), Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 161-183, 2008.

Michael Watkins, "Breakthrough Business Negotiation," (15 June 2002), Jossey-Bass.

Mirsad Hadzikadic and Min Sun, "A Complex Adaptive System (Cas) For Finding The Best Strategy For Prisoner’s Dilemma," (2007), ICCS Available from: <http://www.necsi.edu/events/iccs7/papers/cf40cbc4ee848219434b81a7d206.pdf> [26

May 2014].

Oliver Baldus, "Patent-Based Cooperation Effects," (2010), Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice,Vol. 5, No. 2.

Olivier De Wolf, "Optimal Strategies In N-Person Unilaterally Competitive Games," (September 1999), CORE Discussion Papers 1999049, Université catholique de Louvain, Center for Operations Research and Econometrics (CORE).

Pekka Sääskilahti, "Economics in Managerial Decision-Making: the Case of Patent Licensing," (April 2012), Oxera Agenda.

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, 2013 "Patent Litigation Study." Available from: <http://www.pwc.com/en_us/us/forensic-services/publications/assets

/2013-patent-litigation-study.pdf>[26 May 2014].

Raiffa, H., "Toward a History of Game Theory," (1992), ed. Weintraub, E. R., Duke University Press, Durham, NC, pp. 165–175.

Randall L. Kiser, Martin A. Asher and Blakely B. McShane, "Let’s Not Make A Deal: An Empirical Study Of Decision Making In Unsuccessful Settlement Negotiations," (September 2008), Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Volume 5, Issue 3, 551-591.

Reiko Aoki and Jin-Li Hu, "Time Factors of Patent Litigation and Licensing," (2003), JournalofInstitutionalandTheoreticalEconomics,ISSN 0932-4569.

Richard Dawkins, "The Selfish Gene," (1990), ISBN- 10: 0192860925.

Richard H. McAdam, "Beyond The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Coordination, Game Theory, And Law," (2009), 82 Southern California Law Review 209.

Siegelman, Peter and Joel Waldfogel, "Toward a Taxonomy of Disputes: New Evidence Through the Prism of the Priest/Klein Model," (1999), The Journalof Legal Studies, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 101-130.

Sugden R, "The Economics of Rights, Cooperation and Welfare," (1986), Oxford:Basil Blackwell, ISBN 0631144498.

T. S. Raghu, Wonseok Woo, S. B. Mohan and H. Raghav Rao, "Market Reaction to Patent Infringement Litigations in the Information Technology Industry," (1 August 2007), Inf Syst Front (2008) 10:61–75.

U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, "Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property," (6 April 1995).

U.S. Government Accountability Office, "Assessing Factors that affect Patent Infringement Litigation Could Help Improve Patent Quality," (August 2013).

World Bank Indicators, "Military Expenditure" (percent of GDP), (1999-2003). Available from <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS> [26 May 2014].

1. 2013 edition of the World Intellectual Property Indicators, 9 December 2013, WIPO. Available from: <http://www.wipo.int/ ipstats/en/wipi/>. [26 May 2014].

2. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, 2013 Patent Litigation Study.

3. Jay P. Kesan and Gwendolyn G. Ball, “How Are Patent Cases Resolved? An Empirical Examination Of The Adjudication And Settlement Of Patent Disputes,” 2006, Washington University Law Review, Vol. 84, No. 2, pp. 237-312.

4. A BATNA is sometimes referred to as a disagreement payoff or backstop payoff.

5. A rational player should not accept an agreement if it is worse than or even slightly better than their BATNA.

6. James L. True, “Arming America: Attention and Inertia in U.S. National Security Spending Available” from: < http://dept. lamar.edu/polisci/TRUE/True_art_tlp.html>. [26 May 2014].

7. e.g. increasing R&D or sales and marketing efforts.

8. World Bank Indicators, “Military Expenditure” (% of GDP), (1999-2003).

9. The average duration of patent litigation is 1.2 years: 1.9 years for summary judgement and 3.1 years for trial. If more than $25 million is at risk, the legal expenses for each player is on average $5.5 million.

10. e.g. from cooperative (offers for licensing/cross-licensing) to combative (litigation and quasi-judicial proceedings).

11. e.g. requesting the Patent Office to re-examine the patents asserted against it. This may result in a temporary stay against any pending court proceedings until the Patent Office makes it decision. If the Patent Office finds that the patents are invalid, the defendant can avoid litigation. It is easier for a defendant to invalidate a patent at the Patent Office since there is no requirement for “clear and convincing” evidence compared to at trial where patents are presumed valid. Another non-litigious alternative is designing-around the patent rights and releasing a substitute product which clearly avoids the scope of the claims.

12. Jean Lanjouw and Mark Schankerman, “Enforcing Intellectual Property Rights,” December 2001, ISSN 0969-4447.

13. Jean Lanjouw and Mark Schankerman, “Protecting Intellectual Property Rights: Are Small Firms Handicapped?,” 2004, Journal of Law and Economics.

14. See http://www.jameswanpatent.com/negotiation.html.

15. e.g. bargaining strength for a plaintiff exists where it is a nuisance for a defendant to mount a defense, the cost of a defense threatens the defendant’s solvency, the plaintiff has a reputation for prosecuting patent lawsuits until the end and views losing lawsuits as a profitable investment in that reputation.

16. Michael J. Meurer, “Controlling Opportunistic And Anti- Competitive Intellectual Property Litigation,” 2003, Boston College Law Review, 44(2): 509–44.

17. U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property, 6 April 1995.

18. Pekka Sääskilahti, “Economics In Managerial Decision- Making: The Case Of Patent Licensing,” April 2012, Oxera Agenda. 19. e.g. to make the defendant less competitive relative to itself by raising their costs without the plaintiff incurring litigation expense.

20. In Ch 7-10, The Art of War by Sun Tzu, states “To a surrounded enemy, you must leave a way of escape.” If this is not done, the defendant would fight more fearsomely as it has nothing to lose because the plaintiff intends to destroy them immediately.

21. Colleen Chien, “From Arms Race To Marketplace: The Complex Patent Ecosystem And Its Implications For The Patent System,” January 2010, Santa Clara Law Review, Articles 121-150.

22. Alberto Galasso, “Broad Cross-License Agreements and Persuasive Patent Litigation: Theory and Evidence from the Semiconductor Industry,” July 2007, EI, 45. Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

23. Patents have a maximum 20-year term covering a technology that could be superseded before patent expiry but access to a new technology and markets may provide an additional revenue stream quickly that exceeds any royalty payments from the patents asserted and could provide a return exceeding 20 years.

24. Chris J. Katopis, “Perfect Happiness?: Game Theory As A Tool For Enhancing Patent Quality,” 2008, Yale Journal of Law and Technology: Vol. 10, Article 9.

25. Steve Jobs, CEO of Apple, Inc. stated: “I will spend my last dying breath if I need to, and I will spend every penny of Apple’s $40 billion in the bank, to right this wrong. I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product ... I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this.”

26. Ample coverage in the news media shows that it takes years to resolve court cases while in the meantime the infringing device(s) will likely be replaced by something new.

27. A commitment is a means to lock yourself into a course of action that you might not otherwise choose.

28. A threat is a response that punishes failure to cooperate with you.

29. A promise is an offer to reward for cooperation with you.

30. e.g. when using a commitment.

31. e.g. the simultaneous moves include: (i) deciding how much to invest in monitoring infringement and preparing for patent assertion activities, (ii) deciding whether to launch a potentially infringing product, or (iii) preparing possible defences against patent assertion.

32. These are: (i) discovery; (ii) claim construction; (iii) summary judgment of infringement; and,(iv) trial/post-trial events (such as post-trial motions, appeal, remand).

33. The critical uncertain events at each stage, except the last (trial/post trial), are viewed as having two possible outcomes: favourable or unfavourable. The trial/post trial outcome stage may have two or more sequential stages, which have three possible outcomes, favourable, unfavourable, and intermediate

34. Avinash K. Dixit and Barry J. Nalebuff, “Thinking Strategically,” 17 April 1993, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 9780393069792.

35. Jay Pil Chou, “Patent Litigation As An Information Transmission Mechanism,” May 1994.

36. Claude Crampes and Corinne Langinier, “Litigation And Settlement In Patent Infringement Cases,” July 2001, RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 33(2), p. 258-274.

37. Devised by John von Neumann in 1928.

38. Olivier De Wolf, “Optimal Strategies In N-Person Unilaterally Competitive Games,” September 1999, CORE Discussion Papers 1999049, Université catholique de Louvain, Center for Operations Research and Econometrics (CORE).

39. Ibid.

40. Joe C. Magee, Adam D. Galinsky and Deborah H. Gruenfeld, “Power, Propensity To Negotiate, And Moving First,” 2007, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 200-212.

41. Gideon Parchomovsky and Alex Stein, “Intellectual Property Defences,” October 2013, Columbia Law Review, Vol. 113, 2013, pp. 1483-1542.

42. e.g. moves characterised as combative or cooperative.

43. Charles C. Cowden, “Game Theory, Evolutionary Stable Strategies And The Evolution Of Biological Interactions,” 2012, Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):6.

44. In the case of Uniloc v Microsoft, the 25 percent reasonable royalty rule (of operating profit before depreciation and taxes) for calculating patent infringement damages is no longer automatic.

45. For U.S. patent litigation, the American rule is that each party is responsible for paying its own attorney’s fees.

46. Jonathan E. Kemmerer and Jiaqing Lu, “Profitability And Royalty Rates Across Industries: Some Preliminary Evidence,” 2008, Journal of the Academy of Business and Economics, Chart 2.

47. See http://www.jameswanpatent.com/negotiation.html.

48. e.g. a defendant who files a countersuit against the plaintiff in retaliation (i.e. the same action the plaintiff initiated), may have different damages awarded. 49. T.S. Raghu, op. cit.

50. T. S. Raghu, Wonseok Woo, S. B. Mohan and H. Raghav Rao, “Market Reaction To Patent Infringement Litigations In The Information Technology Industry,” 1 August 2007, Inf Syst Front (2008) 10:61–75.

51. e.g. decisions include: whether to commence a patent dispute and its timing, the number and selection of patents to assert, the number of infringing products to enforce against and choosing an acceptable means to fully resolve the dispute.

52. Elias G. Carayannis and Jeffrey Alexander, “The Wealth Of Knowledge: Converting Intellectual Property To Intellectual Capital In Co-Opetitive Research And Technology Management Settings,” 1999, International Journal of Technology Management, Volume 18 (3-4), page 27.

53. Oliver Baldus, “Patent-Based Cooperation Effects,” 2010, Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 2010, Vol. 5, No. 2.

54. The Chicken game requires both players to move simultaneously and only once choosing either: swerving off the road (cooperate) or going straight (combat).

55. J. Maynard Smith & G. R. Price, “The Logic of Animal Conflict,” November 1973, Nature 246, 15 - 18.

56. Richard H. McAdam, “Beyond the Prisoner’s Dilemma: Coordination, Game Theory, and Law,” 2009, 82 Southern California Law Review 209.

57. e.g. the patentee must prepare their lawsuit, evaluate the strength of its patents and whether the defendant’s products fall within its scope. A defendant can simply stop the alleged infringing act after it has been notified.

58. Raiffa, H., “Toward a History of Game Theory,” 1992, ed. Weintraub, E. R., Duke University Press, Durham, NC, pp. 165–175.

59. Charles A. Holt and Alvin E. Roth, “The Nash Equilibrium: A Perspective, 2004, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 101, 12, March 23 2004, 3999-4002.

60. Bengt Carlsson and Stefan Johansson, “An Iterated Hawkand- Dove Game,” 1997, ISBN:3-540-64769-4.

61. e.g. uncertainty comes from external parties, a judge or jury, etc. First Player Second Player Defendant Plaintiff Oligopolist or Smaller Player Oligopolist

62. e.g. by making the defendant less competitive on price through increasing its cost of production.

63. e.g. by immediately accessing new markets and third party technology without investing a large amount of its own capital in R&D and avoid delay from R&D duplication.

64. Refer to reason stated at: http://www.jameswanpatent. com/negotiation.html.

65. e.g. commencing an ITC Action or proceeding to a pretrial hearing such as a Markman hearing.

66. Richard Dawkins, op. cit.

67. e.g. continue to invest in R&D, innovate and file patents on inventions for new products.

68. e.g. publicly announcing in a positive sense the settling of patent disputes before trial, or agreeing to cross-license with other players.

69. e.g. incumbents may see themselves as innovators that invest heavily in R&D to benefit the market, while new entrants are categorised as low cost imitators that are free-riding off the innovators’ intellectual property.

70. Devised by Anatol Rapoport in 1984.

71. Devised by Martin Nowak and Karl Sigmund in 1993.

72. i.e. you were combative and the opponent cooperated, or you both cooperated.

73. i.e. you cooperated but your opponent was combative, or you were both combative.

74. Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin, “From extortion to generosity, evolution in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110: 15348-15353.

75. Jeremy W. Bock, “Neutral Litigants in Patent Cases,” 2 January 2014, North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology, Volume 15, Issue 2.

76. Corina E. Tarnity, Tibor Antal and Martin A. Nowak, “Mutation-Selection Equilibrium In Games With Mixed Strategies,” 29 July 2009, Journal of Theoretical Biology, 261 (2009) 50–57.

77. e.g. a small sized market or a low profit market.

78. e.g. Apple v. Samsung Electronics in the smartphones/ table computer patent lawsuits, since 15 April 2011.

79. e.g. comparing claim charts, the size of their patent portfolio, or past victories in patent infringement.

80. Jasvir K. Grewal, Cameron L. Hall, Mason A. Porter and Marian S. Dawkins, “Formation Of Dominance Relationships Via Strategy Updating In An Asymmetric Hawk-Dove Game,” 27 August 2013. Available from: <http://io43.com/pdf/1308.5358. pdf>. [26 May 2014].

81. Kevin Mitchell and James Ryan, “Game Theory Models Of Animal Behaviour,” 2003, COMAP, Inc.

82. e.g. offer a license but if it is refused, then litigate.

83. e.g. litigate first until countersuit is filed, then offer a license, etc.

84. The reasoning is because you have better information concerning your own patents, and the opponent has better information concerning theirs.

85. Jasvir Kaur Grewal, “Cooperation versus Dominance Hierarchies in Animal Groups,” September 2012, Oriel College, University of Oxford.

86. e.g. a patentee can reassure itself of the patent’s strength by seeing what prior art a defendant has raised in their defence, or the defendant can reassure itself of the patent’s weakness after presenting the prior art in its defence.

87. Recently affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2011 in the Microsoft Corp. v. i4i Limited Partnership case.

88. If the patent is enforced again against another infringer, and the validity is unsuccessfully challenged again, the second infringer must pay close to the actual costs incurred by the patentee in defending the challenge.

89. John R. Allison, Mark A. Lemley and Joshua Walker, “Extreme value or trolls on top?,” December 2009, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 158, No. 1.

90. In other words, did the implemented strategy produce an outcome that was better than the outcomes of alternate strategies.

91. Jennifer Golbeck, “Evolving Strategies for the Prisoner’s Dilemma,” February 2002, Advances in Intelligent Systems, Fuzzy Systems, pp. 299-306.

92. Cooperation can be quickly restored if lost.

93. Non-cooperation is always punished.

94. e.g. the rules are simple, straightforward and always the same.

95. Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., No. 2010-1510 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 10, 2012).

96. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, op. cit.

97. Jianzhong Wu and Robert Axelrod, “How to cope with noise in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma,” March 1995, The Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 39, Issue 1, pp. 183-189.

98. Sugden R., “The Economics Of Rights, Cooperation And Welfare,” 1986, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

99. Martin Nowak and Kari Sigmund, “A Strategy Of Win- Stay, Lose-Shift That Outperforms Tit-For-Tat In The Prisoner’s Dilemma Game,” 1 July 1993, Nature, Vol. 364, pp. 56-58.

100. Randall L. Kiser, Martin A. Asher and Blakely B. McShane, “Let’s Not Make A Deal: An Empirical Study Of Decision Making In Unsuccessful Settlement Negotiations,” September 2008, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Volume 5, Issue 3, 551-591.

101. Statistica, “Global Market Share Held By Leading Smartphone Vendors From 4Th Quarter 2009 To 3rd Quarter 2014.” Available from: <http://www.statista.com/ statistics/271496/global-market-share-held-by-smartphonevendors- since-4th-quarter-2009/>. [9 January 2015].

102. Mary Meeker, presentation at Internet Trends D11 Conference, 29 May 2013.

103. Available from http://www.news.com.au/technology/ is-the-shine-coming-off-the-iphone-apple-loses-market-share-tosamsung- in-smartphone-wars/story-e6frfro0-1226686645654. [9 January 2015].

104. Plaintiff’s exhibit no. 154, page 1.

105. USPTO, “Patenting by Organizations 2010.”

106. Kurt Eichenwald, “The Great Smartphone War.” Available from: <http://www.vanityfair.com/business/2014/06/ apple-samsung-smartphone-patent-war/> [9 January 2015].

107. Defendant’s exhibit no. 586.003.

108. Apple originally asked for the trial to commence on 1 February 2012 to capitalise on its first mover advantage.

109. Apple was originally seeking U.S.$2.525 billion in damages.

110. Chinese smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi founded in June 2010, now holds 5.2 percent global market share. Chinese smartphone manufacturer Huawei has increased its global market share from 1.5 percent (2010) to 6.9 percent (2014).

111. Available from http://www.businessweek.com/ articles/2013-12-09/apple-samsung-patent-wars-meanmillions- for-lawyers. [9 January 2015]. 112. August 2012.

113. March 2013.

114. November 2013