les Nouvelles August 2019 Article of the Month

China Specialized IP Courts:

Substance Or Theater?

Part I

Institute of Scientific& Technical Information of Shanghai

Patent Analyst

Shanghai, China

Introduction

Since 2008, the Chinese government has undergone great efforts to enhance its nationwide IPR protection system. A significant milestone in this undertaking is the establishment of three Specialized IP Courts, the Beijing Specialized IP Court (BIPC), the Shanghai Specialized IP Court (SIPC) and the Guangzhou Specialized IP Court (GIPC). On August 31, 2014, the SCNPC issued the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on Establishing Intellectual Property Right Courts in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou (“Decision”).1 This Decision officially announced the establishment of Specialized IP Courts under the Constitution and the Organic Law of the People's Courts of the People's Republic of China. The BIPC was established on November 6, 2014, followed by GIPC, which was established on December 16, 2014, and the SIPC was established on December 28, 2014. There are several reasons for these three venues. First, these three regions received the largest volume of IP disputes. In 2017, the IP cases received by the courts in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong Province, Jiangsu Province and Zhejiang Province constituted 70.65 percent of the total IP cases filed in the PRC courts.2 Second, these three regions are the most developed regions in China and host many high-tech companies. Third, these three regions have sophisticated legal and IP communities. Finally, these three regions have considerable foreign interactions.

The China Specialized IP Courts were established under pro-innovation policies and policies emphasizing the importance of IPR judicial protections. Since 2008, the Chinese government successively issued the Outline of National Intellectual Property Strategy, the Deepening the Judicial Reform in China, the Innovation-Driven Development Strategy and the China Program for Judicial Protection of IPR (2016-2020). These pro-innovation policies were formulated to promote economic transformation from an investment and export driven economy to a consumption and innovation driven economy. These policies promote the replacement of the environmentally harmful industrial structure with IP-dependent high-end manufacturing in order to mitigate conflicts between the increasing demand for resources and resulting environmental problems. Meanwhile, China also realized the importance of enhancing judicial IPR protection to safeguard these innovative activities. The establishment of China's Specialized IP Courts may have only been partially driven by these policies, however. Their establishment may have also been inevitable due to the increasing trend of IP litigation, especially patent litigation, in PRC courts and the rising numbers of countries and regions where Specialized IP Courts have been set up.

To date, the China Specialized IP Courts have been running for more than three years. In 2017, under the requirements of the Decision made in 2014, the SPC made a report to the SCNPC on the work of the three Specialized IP Courts. According to the report, the three Specialized IP Courts run well and have “significant importance on further implementation of the National Intellectual Property Strategy and the Innovation-driven Development Strategy.”3 In comparison, foreign countries, especially the U.S., still view China's IP protections negatively. In 2017, the Trump Administration instructed the USTR to initiate a §301 investigation of China to look into Chinese laws, policies, and practices that may force U.S. companies to transfer the know-how secret and technology to Chinese joint venture companies and in doing so harming U.S. companies' IPR. Also, according to the USTR's report to Congress in 2017 on China's WTO compliance, China is still weak in protecting and enforcing IPR, causing IPR holders to face a complex and uncertain IPR enforcement environment in China.

Comparing the SPC's annual report with the U.S. government's negative comments, this article seeks to explore whether China's Specialized IP Courts truly improve the judicial protection of IP in China, what problems exist in this system, and what impact this system will have on foreign companies.

This article addresses the above issues in Part I and Part II. Part I begins with the policies behind the establishment of China's Specialized IP Courts and analyzes the nexus between the policies underlying the Specialized IP Courts, the mission of each policy, the rationales behind the policies, and comparing these approaches in relation to achieving their missions. Part I then addresses the necessity of the Specialized IP Courts based on the increasing number of domestic patent applications, PCT applications, as well as patent lawsuits. Also, it addresses the necessity of the courts in light of the negative comments and actions from the U.S. government and private companies and furthermore views necessity in the context of global IP harmonization. Part I finally conducts a comparative study of China's Specialized IP Courts in light of jurisdictions and justiciability and introduces unique organs and features of China's Specialized IP Courts.

I. The Policies Behind the China Specialized IP Courts

According to the Decision, the mission of the Specialized IP Courts is to promote the implementation of the National Intellectual Property Strategy and to guarantee the Innovation-driven Development Strategies.

The Chinese government formulates these pro-innovation and IP protection strategies, because the government sees it is of great strategic importance to develop and utilize knowledge-based resources to transform patterns of economic development. Since 1978 when the “Reform and Opening up” policy was introduced, China has experienced an economic boom and social development. China has become the second largest economic entity in the world and has maintained a GDP growth rate around seven percent. However, in the past years, the economic growth in China relied much on exports and investment. The exports and investment driven trajectory made China a “World Factory” but caused a number of serious problems. One of the biggest problems is the environmental pollution. China needs to change the economic growth trajectory in order to mitigate the conflicts between its increasing demand for resources and resulting environmental problems. As a result, the government initially announced economic transformation from investment/ exports driven economy to consumption/innovation driven economy in the 11th five-year plan.

The Chinese government meanwhile realized that indigenous innovation on knowledge-based resources is a key to the transformation. Technical innovation will play a prominent role in China's economic and social development. Since then, the government issued numbers of pro-innovation policies to advance the transformation. The policies include “Made in China 2025” which addresses the approaches to develop high-ending manufacture and to reform the industrial structure.4 The policies also include the “Outline of the National IP Strategy” which improves the nation's capacity for innovation and enhance the protection on innovation, and the “Innovation-driven Development Strategy” which further sets the milestones and approaches on innovation development.

A. Outline of National Intellectual Property Strategy

On June 25, 2008, the National Intellectual Property Strategy was issued by the State Council of the PRC. This is the first national strategy which sets a goal to establish the Specialized IP Courts. The strategy states “Explore issues on setting up courts of appeal for cases involving IP. Judicial organs for handling cases involving IP need to be further strengthened and well-staffed to improve the handling of cases and enforcement of law.”5

This strategy aims to improve China's capacity to create, utilize, protect and manage IP, making China an innovative country. The strategy sets up a milestone that by 2020, China will become a country with a comparatively high level in terms of the creation, utilization, protection and administration of IPRs.

Besides, the strategy stated that efforts to improve the national innovation capacity will be supported by the Judicial Reform. In the following years, allocation of judicial resources will be optimized and remedy procedures will be simplified. The government will explore to establish a “Three-In-One” trial model, to centralize jurisdiction over cases involving patents or other cases of a highly technical nature, to set up courts of appeal for cases involving IP, and to strengthen the judicial organs for handling cases involving IP and to improve the judicial expertise on the IP disputes.

B. Innovation-Driven Development Strategy

In May, 2016, the State Council of the People's Republic of China announced the “Innovation Driven Development Strategy” and placed the strategy as a top priority and emphasized innovation as one of the five development principles in its 13th Five-year Plan.

As stated above, this strategy was formulated under the context of economic transformation from exports/ investment driven to innovation/consumption driven economy. This strategy proposed to deepen reform in the IP industry, to improve IPR creation, utilization, protection and management capabilities, to promote the commercialization of innovation and to enhance basic security role of the IP system in innovation. The strategy aims to strengthen the core competitiveness of the country; to help China achieve win-win situations with the rest of the world.

This strategy also set up “three-step” milestones. The first step, by 2020, China will build a nationwide innovation system, creating more optimized environment for innovation, making more complete policies and regulations encouraging innovation, enhancing intellectual property protection. The second step, by 2030, China will join the leading group of innovative countries. The third step, by 2050, China will grow into a world class scientific and technological innovation powerhouse.6

C. Deepening the Judicial Reform in China

Since 2013, Xi's government has been making efforts to promote the reform in the Chinese judicial branch. China's People's Congress Central Committee issued the “Decision of the CCCPC on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform” on November 12, 2013.7 The decision was made under the current situation of weakness in scientific and technological innovation, the unbalance of the industrial structure, the huge development gap between urban and rural areas, as well as between regions and of the disparities of incomes. In a word, this reform is made consistent with the principles of the National innovation strategies.

The Decision explicitly states under the “Deepening reform of the management system for science and technology” section that the Chinese government in the following years will strengthen the application and protection of IPR, improve the technological innovation incentive mechanism, and explore ways to set up IPR courts.

Further, the Decision puts forward various ways including to establish a judicial jurisdiction system that is appropriately separated from the administrative divisions, to enhance the judicial power and responsibility for handling cases by the presiding judge and the judges' panel. These measures aim to promote the independence of judicial departments exercising their judicial powers, to improve a clear right-responsibility judicial power and to improve the judicial transparency and credibility.

D. China Program for Judicial Protection of IPR (2016-2020)

As the three-year working report by SPC stated, the establishment of the three Specialized IP Courts has the significant meaning on further implementation of National innovation and IP policies. The significance could be reflected in the China Program for Judicial Protection of IPR (2016-2020) issued after three-year's operation of the China Specialized IP Courts. This strategy interprets the approaches in details enhancing the IP judicial protection including further promote the “Three-In-One” adjudication model, further standardize the burden of proof on IP litigations, further improve the technical investigation in IP tribunals, further implement the case-guidance system and further improve the damages calculation standards.8 The working of Specialized IP Courts proved the feasibility of the approaches and also reflects certain problems that should be solved by the whole IP judicial branch in the next five years.

II. The Necessity to Establish the China Specialized IP Courts

A. Large Volume of China's Patent Applications

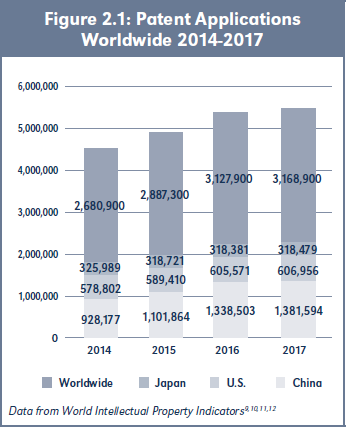

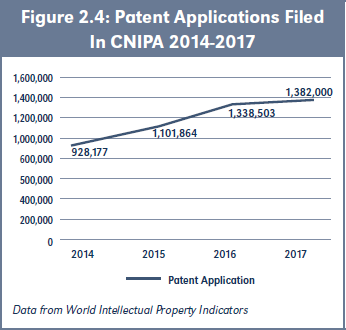

According to the statistics from WIPO annual report, the number of Chinese patent applications filed in China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) have been ranked at the top for seven consecutive years. And the number is still increasing rapidly by 15 percent of average growth rate. In 2016, CNIPA received 1.3 million Chinese patent applications, more than the total of the USPTO, JPO, KIPO and EPO. In 2017, Chinese patent applications doubled the number of U.S. patent applications and share 43.6 percent of the worldwide total applications. China now is the main driver of the global growth of patent applications. See Figure 2.1.

According to the statistics from WIPO annual report, the number of Chinese patent applications filed in China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) have been ranked at the top for seven consecutive years. And the number is still increasing rapidly by 15 percent of average growth rate. In 2016, CNIPA received 1.3 million Chinese patent applications, more than the total of the USPTO, JPO, KIPO and EPO. In 2017, Chinese patent applications doubled the number of U.S. patent applications and share 43.6 percent of the worldwide total applications. China now is the main driver of the global growth of patent applications. See Figure 2.1.

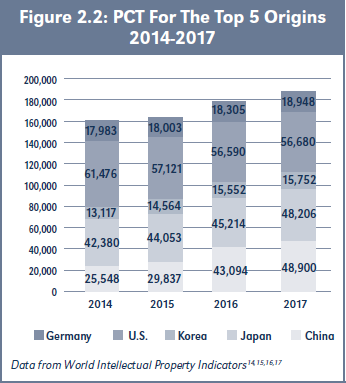

Meanwhile, the PCT patent applications filed by Chinese applicants also are rising dramatically since 2014. In 2017, The number of PCT filed by Chinese applicants reached 48,900, for the first time surpassing Japan and reaching to the second in the world. Besides, Chinese companies have received the U.S. patents by tenfold in less than 10 years. Chinese mainland inventors received 11,241 U.S. patents in 2017, a 28 percent increase over the same period in 2016.13 This propels China into the top five recipients for the first time, behind the U.S., Japan, Korea and Germany but ahead of Taiwan. See Figure 2.2.

B. Increasing Patent Disputes in China

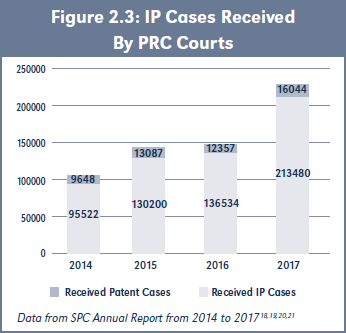

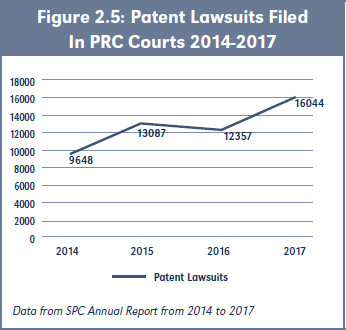

The IP disputes in China are rising accordingly. The statistics show that the number of IP lawsuits filed in PRC courts is growing year by year and historically broke 0.2 M in 2017. See Figure 2.3. The same trends can be shown in patent lawsuits. The number is growing from 9,648 to 16,044; almost doubled in four years. See Figure 2.4. Even though there is no strong evidence proving that the growing patent applications directly result in the growing patent disputes, the connection between the two is undeniable. As a result, IP courts other than IP tribunals are necessary for dealing with the large IP caseloads. See Figure 2.5.

C. Negative Views by Foreign Parties to China IP Protection

In the past decades, China has received negative comments from foreign countries, especially the U.S. towards the IP protection. China is a well-known “World Factory” but meanwhile is notorious for the serious counterfeit and piracy problems. China has been placed on the Priority Watch List in USTR's special §301 report several times. Not only the U.S. government but the U.S. private companies who do business in China express serious concerns about their IPR protection in China mainland. The U.S. companies doubt independence of China's judiciary. In their experience and observation, Chinese judicial branch has been greatly influenced by political, government or business pressures, particularly outside of China's big cities.22

In 2017, the USTR issued its annual report on China's WTO compliance. In this report, USTR admitted China's efforts to comply with the WTO regulations including revising the laws and regulations, issuing the IP protection policies to combat the IP infringement and the sale of shoddy goods. However, the IPR enforcement still remains a serious problem throughout China. And the inadequacies in China's IPR protection and enforcement regime present serious barriers to U.S. exports and investments.23 In details, the USTR pointed out the serious trade secret theft in China that deprived the U.S. companies' IP rights on trade secrets when they do business with Chinese companies. And USTR also states that “secure and controllable” requirement in various regulations imposed the restrictions on foreign investments and also contribute to the technique know-how misappropriation by Chinese companies. These regulations also call into question China's prior bilateral commitments to treat IP owned or developed in other countries the same as IP owned or developed in China.24 Besides, USTR addressed the problems of bad faith trademark registration in China. As for the IPR enforcement, USTR pointed out that the overall IPR enforcement is hampered by inefficient civil recourse mechanisms, as demonstrated by resource constraints, lack of training, lack of initiative, lack of transparency in the enforcement process and its outcomes, procedural obstacles to civil enforcement, lack of coordination among Chinese government ministries and agencies, and local protectionism and corruption.25 All in all, the USTR doesn't view China well in IPR protection and enforcement, and expressed that the U.S. IPR holders would be harmed by the overall IPR environment in China.

Meanwhile, in 2017, the USTR formally initiated an investigation of China under §301 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended. The investigation aims to determine whether acts, policies, and practices of the Government of China related to technology transfer, IP, and innovation are unreasonable or discriminatory and burden or restrict U.S. commerce.26 Then on April 3, 2018, the USTR announced its intent to implement tariffs on certain products imported from China.

The recent annual report, as well as the §301 investigation at least conveyed the information that China still needed to enhance the IPR protection and enforcement for foreign IPR holders. Even though the Specialized IP Courts had been established, the unchanged negative views from foreign parties, as well as the hostile actions by the foreign government show that China still has to make more efforts to enhance the IP judicial protection.

D. Global IP Harmanization

Because of the global trade, IP is no longer a domestic issue. As more and more IP related treaties were formulated, and as more and more states joined the treaties for the needs of global trade, IP has become an important international issues. WIPO has established global protection system to better protect the IP interests of the inventors global wide. The establishment of the PCT provides a great convenience and reduces cost for the inventors who want to obtain the patent rights from various countries. Also in recent year, the five IP offices in U.S., China, Europe, Korea and Japan cooperated together as an IP5 to further the patent harmonization of practices and procedures, enhance work-sharing, high-quality and timely search and examination results, and seamless access to patent information to promote an efficient, cost-effective and user-friendly international patent landscape.27 Besides, in 2011, U.S. enacted the America Invents Act, changing the patent law from first-to-invent system to first-inventor-to-file system. This change was made to comply with the global patent application filing system. Therefore, not only the international society is trying to harmonize the IP issues but also the domestic IP laws are experiencing the harmonization.

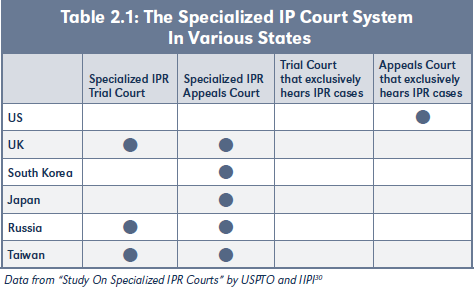

Under the global IP harmonization, 31 countries and regions have already established the IPR courts, including Canada, Japan, Korea, Russia, Taiwan, UK, U.S., etc. according to the report by USPTO and IIPI.28 See Table 2.1. Besides, until 2014 all of the IP5 members except China have established or are on the progress to establish the IP courts. The U.S. has established the CAFC to adjudicate nationwide patent disputes, Korea and Japan has established Specialized IPR Appeals Court, and the unitary patent court of EU is in progress.29 Therefore, the establishment of the China Specialized IP Courts seems inevitable.

III. Characters of China Specialized IP Courts

A. Compared with Foreign Specialized IP Courts: What's the Difference?

The Chinese government learned the experiences from the U.S. and Japan when designing the China Specialized IP Courts. However, they still remain their own characters of jurisdiction and justiciability.

1. Difference in Jurisdiction

According to the “Provisions on the Jurisdiction of the Intellectual Property Courts of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou over Cases” issued by SPC in 2014, the Specialized IP Courts are in the intermediate level and they are under the direct supervision of the People's High Court in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong Province.31

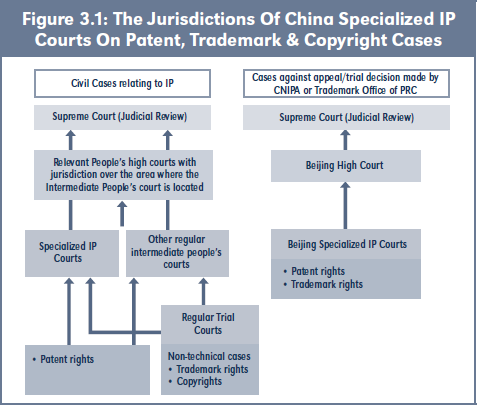

Three Specialized IP Courts have original jurisdiction, appellate jurisdiction, geographical jurisdiction, as well as exclusive jurisdiction. The courts have original jurisdiction on civil or administrative cases involving patents, new plant varieties, integrated circuit layout design, technical know-how, software and on the cases involving the certification of well-known marks within Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The courts have appellate jurisdiction on civil and administrative trademark and copyright cases from basic People's Courts within Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. In other words, the courts review the decisions from the basic People's Courts over civil and administrative trademark and copyright cases. Besides, the GIPC also has the cross-regional jurisdiction on the first instance civil or administrative cases involving patents, new plant varieties, integrated circuit layout design, technical know-how, software and on the cases involving the certification of well-known marks within the Guangdong Province. Further, Beijing specialized IP court has exclusive jurisdiction on administrative cases over the declaration of intellectual property rights, over the verdict of compulsory license and royalty measures and over other administrative acts by the IP administration department under the State Council. These administrative cases involve patents, trademark, new plant varieties and IC layout design.32 For example, if the party files the petition to invalidate a patent in Patent Reexamination Board (PRB) of CNIPA and the party disagrees with the decision from PRB, the party can only file the lawsuit in Beijing specialized IP court to review the decision. See Figure 3.1.

There is a similarity between theChina Specialized IP Courts and the U.S. CAFC. Both the BIPC and CAFC have the nationwide jurisdiction hearing the appeals from the decisions on the grant of patent right or trademark right, from the decisions on validity of patent right or trademark right by the IP administrative department of the state. However, the China Specialized IP Courts are distinctive from CAFC in many aspects. First, CAFC has nationwide appellate jurisdiction over IP cases involving patents while the China Specialized IP Courts have the original jurisdiction over IP civil cases involving patents from Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong Province. Therefore, the civil cases involving patent disputes which have no connection with Beijing, Shanghai nor Guangdong Province will not go to the Specialized IP Courts. Second, CAFC only has jurisdiction on limited matters related to patents or trademark, while the China Specialized IP Courts have jurisdiction over IP issues in broader scope.

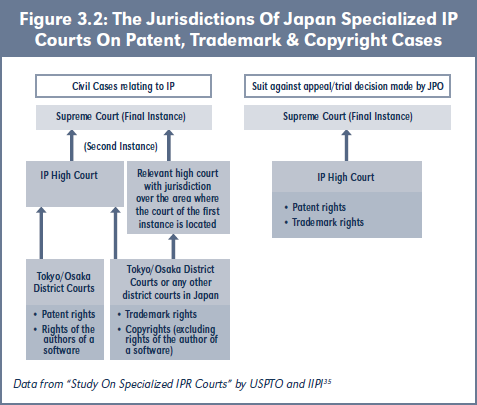

The China Specialized IP Court system is also distinctive from Japan IP court system though both in the civil law system. Japan has the IP High Court, which was established in 2005 as a special branch of the Tokyo High Court. In Japan, all the patent infringement litigation will firstly go to the Tokyo District Court and the Osaka District Court. The appeals from these two courts will be reviewed by IP High Court.33 In a word, the IP High Court has the appellate jurisdiction on the nationwide patent infringement cases. Meanwhile, the IP civil cases involving trademark or copyright still follow the regional jurisdiction. Thus the IP High Court can only hear the trademark or copyright civil cases which are within its geographical jurisdiction. With respect to the administrative litigation against decisions issued by the JPO including decisions on patent invalidation, only the IP High Court has first instance jurisdiction over these disputes.34 Similarly, the BIPC also has the exclusive jurisdiction hearing the disputes arising from the decisions on certain IPR by the IP administration department under the State Council. However, unlike the IP High Court which has the appellate jurisdiction on the patent infringement cases nationwide, the China Specialized IP Courts have the original jurisdiction other than the appellate jurisdiction on the patent infringement cases and such jurisdiction is limited in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong Province. See Figure 3.2.

Although the differences exist, the principles to set up various Specialized IP Courts are the same. These courts are set up to achieve greater predictability and uniformity of the decisions by centralizing the jurisdiction over IP cases, especially the patent cases.

2. Difference in Justiciability

It is known that the CAFC has justiciability on validity of the patent in the patent infringement cases. In other words, in the patent infringement cases, the defendant can invalidate the patent. Both the validity and the infringement issues can be tried by the same court. In Japan, before the establishment of IP High Court, a court cannot decide the validity of a patent in a patent infringement suit. Instead the court stays the proceeding until the patent was held invalid through decisions made by the JPO at invalidation trials. This bifurcated trial was finally changed in 2000. Now the court can also decide the validity of patent in the infringement cases like the CAFC does.36

The traditional IP tribunals in China also adopted a bifurcated trial system. And unlike Japan, three newly established Specialized IP Courts retain the bifurcated trial system. The Courts have no justiciability on the patent validity issues in the infringement cases and instead were only able to stay until the patent was held invalid through administrative decisions made by PRB in CNIPA.

B. Compared with the Regular IPR Tribunals in PRC Courts: What's New?

1. Less Administrative Intervene Structure

The China Specialized IP Courts have new court structure that is designed to follow the instructions set forth in “Deepening the Judicial Reform In China.” The instructions are to establish a judicial system that is appropriately separated from the administrative divisions and to enhance the judicial power and responsibility for handling cases by the presiding judge and the collegiate bench.37

In the traditional IP tribunal organization, the administrative superior which is named the Judicial Committee has the final say on the case decisions. The members of the Judicial Committee include dean of the court, the chief judges of the divisions and other communist party officials from the administrative divisions. The Judicial Committee does not fully participate in the trial proceeding and only hears the reports from the judges about cases. The judges' decisions or decisions by the judges' panel will not become final until they are approved and signed by the Judicial Committee.

The three Specialized IP Courts eliminated the administrative influence on the decisions of the cases. A three-judge panel works on each case and one of them is the presiding judge. The presiding judge takes the major responsibility for the case decisions.38 The decisions made by the judges or the panel will not be reviewed by the Judicial Committee. Therefore, the new organization of the IP court has weakened the administrative role in the cases and enhance the judicial independence.

Specifically, the BIPC has six judicial divisions, one for filing and docketing, four trial divisions and one supervision and retrial division. The judges are divided into two categories, the 51 judges and other assistant judges. The SIPC operates jointly with Shanghai 3rd Intermediate Court. The SIPC has its independent two trial divisions while sharing administrative divisions with the Shanghai 3rd Intermediate Court. The GIPC has six divisions, one for filing and docketing, one patent trial division, one copyright trial division, one trademark and unfair competition division, one investigation office and administrative office.

2. Technical Investigator Mechanism

Another highlighted change is introducing the technical investigators to the trials. The SPC respectively issued two provisions on the regulations on the technical investigators of IP courts in 2014 and in 2017,39,40 addressing the role and the duty of the investigators. The investigators are a group of engineering professors, patent examiners who have the expertise on technology issues. They assist the judges dealing with IP cases involving high technical complexity. The technical investigator will participate during the litigation asking technical questions to litigant participants, stating opinions on the technical issues of the cases, answering technical questions to the judges. Also the investigators will participate in the discovery proceeding. (The judges in PRC courts have authority to conduct perpetuation of evidence for plaintiffs.) However, the investigator has no vote on the results of the judgement.41 Accordingly, the investigators are auxiliary staffs in the IP courts. According to the report from SPC, the China Specialized IP Courts have already set up the investigation offices. By 2017 the Courts have hired 61 technical investigators from various technology industries. The investigators participated in total of 1,144 IP cases providing the expert advices on technical issues to the judges.42

The assistance of technical investigators will increase the accuracy of factor finding. Although the judges appointed by the IP courts mostly have eight to 10 years working experiences over IP cases, many of them have no technical background. The investigators can cure the defects and relieve the burden on the judges dealing with the technical issues. This may leave judges more time to the legal aspects of the case. Therefore, under the cooperation, the cases will be handled in a more efficient way and the outcome of the cases will be more accurate.

3. Case Guidance System

The case guidance mechanism is not a unique character of Specialized IP Courts. The system was established by SPC in 2010 and was nationwide promoted by the SPC under the context of Deepening the Judicial Reform. The principle of the case guidance is that the subsequent cases should be adjudicated in accordance with effective judgements and rulings of prior similar cases.43 Generally, in practice, Chinese judges will refer to the ruling of prior cases when handling the cases. The prior cases may be those specially selected by the SPC or its affiliated institutions. These cases will be found in the official case databases including Peking University's Chinalawinfo or China Judgements Online. Judges dealing with cross-border matters may also look to leading Hong Kong or foreign cases.44 However, the establishment of the case guidance mechanism does not mean that China's legal system is changing from civil law system into common law system. Unlike common law system, the PRC courts under the case guidance system have no obligation to cite the prior cases. The prior cases are only persuasive, not necessary. The goal of the case guidance system is to unify the application of rule of laws.

Although the case guidance was introduced to be applied to the whole judicial system, it was led by the IP judicial branch. The SPC has been systematically selecting and issuing 10 model IP cases or 50 typical IP cases since 2009. These prior cases selected and issued by SPC could be the citing resources for all the IP courts and tribunals. Especially, the BIPC is the pioneer exploring the case guidance system. In 2015, it launched its own IP case guidance database which is supported by big data technology. This database constitutes of three subsystems which are case target and review system, case issuance system and case application system. The prior cases resources should be SPC guiding cases, SPC typical cases, other SPC cases, High People's Court model cases, High People's Court reference cases, other prior cases from High People's Courts, Intermediate People's Court precedent, Basic Court precedents and Foreign (Non-mainland) case precedents.45 So far with the joint efforts by legal academics, legal database companies and law professionals, the database has included more than 500 guiding prior cases.46

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN):

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3317007.

Abbrevations

|

BIPC

|

Beijing Specialized IP Court

|

|

SIPC

|

Shanghai Specialized IP Court

|

|

GIPC

|

Guangzhou Specialized IP Court

|

|

SCNPC

|

Standing Committee of the National People's Congress

|

|

PRC

|

People's Republic of China

|

|

IPR

|

Intellectual Property Right

|

|

IP

|

Intellectual Property

|

|

USTR

|

United States Trade Representative

|

|

SPC

|

Supreme People's Court

|

|

PCT

|

Patent Cooperation Treaty

|

|

CAFC

|

Court Of Appeals For Federal Circuit

|

|

GDP

|

Gross Domestic Product

|

|

CCCPC

|

China People's Congress Central Committee

|

|

WIPO

|

World Intellectual Property Organization

|

|

CNIPA

|

China National Intellectual Property Administration

|

|

USPTO

|

United States Patent and Trademark Office

|

|

JPO

|

Japan Patent Office

|

|

KIPO

|

Korean Intellectual Property Office

|

|

EPO

|

European Patent Office

|

|

IIPI

|

International Intellectual Property Institute

|

|

PRB

|

Patent Reexamination Board

|

- Quanguo Renda Changweihui Guanyu Zai Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou Sheli Zhishichanquan Fayuan Jueding (全国人大常委会关于在北京、上海、广州设立知识产权法院的决定) [Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on Establishing Intellectual Property Right Courts in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou](Promulgated by Standing Comm. Nat’l People’s Cong. August 31, 2014, Effective August 31, 2014) CLI.1.232867 (Lawinfochina).

- Zhang Lei(张蕾), Xinshou Zhichan Minshi Yishenan Jizeng Wucheng (新收知产民事一审案激增五成), translated in The Number Of The First Instance Civil Cases Received In PRC Courts Increase By 50 percent (April 23, 2018, 10:31a.m.), https://www. chinacourt.org/article/detail/2018/04/id/3275038.shtml.

- Zuigao Renmin Fayuan Guanyu Zhishichanquan Fayuan Gongzuo Qiangkuang Baogao (最高人民法院关于知识产权法院工作情况的报告) [Supreme Court’s Report on the work of Intellectual Property Courts of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. August 29, 2017, Effective August 29, 2017) CLI.3.301048 (Lawinfochina).

- Guowuyuan Guanyu Yingfa “Zhongguo Zhizao 2025” Tongzhi (国务院关于印发《中国制造2025》的通知) [Notice of the State Council on Issuing the “Made in China (2025)”] (Promulgated by St. Council May 08, 2015, Effective May 08, 2015) CLI.2.248573 (Lawinfochina).

- Guowuyuan Guanyu Yingfa Guojia Zhishichanquan Zhanlve Gangyao Tongzhi (国务院关于印发国家知识产权战略纲要的通知) [Notice of the State Council on Issuing the Outline of the National Intellectual Property Strategy] (Promulgated by St. Council June 05, 2008, Effective June 05, 2008) CLI.2.105764, §45, (Lawinfochina).

- Guojia Chuangxin Qudong Fazhan Zhanlve Gangyao (国家创新驱动发展战略纲要) [Innovation-driven Development Strategy] (Promulgated by St. Council May, 2016, Effective May, 2016) CLI.5.270576 (Lawinfochina).

- Zhonggong Zhongyang Guanyu Quanmian Shenhua Gaige Ruogan Zhongda Wenti Jueding (中共中央关于全面深化改革若干重大问题的决定) [Decision of the CCCPC on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform] (Promulgated by People’s Ct. Central Comm. November 12th, 2013, Effective November 12th, 2013) CLI.5.213067 (Lawinfochina).

- Zuigao Renmin Fayuan Guanyu Yingfa “Zhongguo Zhishichaquan Sifa Baohu Gangyao (2016-2020) Tongzhi (最高人民法院关于印发《中国知识产权司法保护纲要(2016-2020) 》的通知) [China Program for Judicial Protection of Intellectual Property Rights (2016—2020)] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. April 20th, 2017, Effective April 20th, 2017) CLI.3.293510 (Lawinfochina).

- WIPO, World Intellectual Property Indicator 2018 (2018) 1,7, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2018.pdf (last visited December 21, 2018).

- WIPO, World Intellectual Property Indicator 2017 (2017) 1,7, http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2017. pdf (last visited May 3, 2018).

- WIPO, World Intellectual Property Indicator 2016 (2016) 1,7, http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2016. pdf (last visited May 3, 2018).

- WIPO, World Intellectual Property Indicator 2015 (2015) 1,6, http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2015. pdf (last visited May 3, 2018).

- The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc., China Enter Top 5 Of U.S. Patent Recipients for The First Time, 95 Bloomberg L.P.1 (2018).

- WIPO, supra note 9, at 67.

- WIPO, supra note 10, at 78.

- WIPO, supra note 11, at 61.

- WIPO, supra note 12, at 57.

- Zhongguo Fayuan Zhishichanquan Sifabaohu Zhuangkuang (2017) ( 中国法院知识产权司法保护状况(2017)) [Report On Judicial Protection In PRC Courts (2017)] (April 19, 2018, 11:53AM) https://www.chinacourt.org/article/detail/2018/04/ id/3272468.shtml.

- Zhongguo Fayuan Zhishichanquan Sifabaohu Zhuangkuang (2016) ( 中国法院知识产权司法保护状况(2016)) [Report On Judicial Protection In PRC Courts (2016)] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. April 2017, Effective April 2017) CLI.3.297656 (Lawinfochina).

- Zhongguo Fayuan Zhishichanquan Sifabaohu Zhuangkuang (2015) ( 中国法院知识产权司法保护状况(2015)) [Report On Judicial Protection In PRC Courts (2015)] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. April 2016, Effective April 2016) CLI.WP.7870 (Lawinfochina).

- Zhongguo Fayuan Zhishichanquan Sifabaohu Zhuangkuang (2014) ( 中国法院知识产权司法保护状况(2014)) [Report On Judicial Protection In PRC Courts (2014)] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. April 2015, Effective April 2015) CLI.WP.6658 (Lawinfochina).

- United States Trade Representative, 2017 Report to Congress On China’s WTO Compliance 1, 141 (2018), https://ustr. gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/Reports/China percent202017 percent20WTO percent20Report.pdf (last visited May 3, 2018).

- See id. at 16.

- See id. at 67.

- See id. at 107.

- See id. at 9.

- Five IP Offices, About IP5 co-operation (May 3, 2018, 10:06 p.m.), https://www.fiveipoffices.org/about.html.

- USPTO, IIPI, Study on Specialized Intellectual Property Courts, 1,11(2012), https://iipi.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/ Study-on-Specialized-IPR-Courts.pdf (last visited May 3, 2018).

- Unified Patent Court, About the UPC (May 3, 2018, 10:06 p.m.), https://www.unified-patent-court.org/

- USPTO, IIPI, supra note 28, at 11-13.

- Zuigao Renmin Fayuan Guanyu Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou Zhishichanquan Fayuan Anjian Guanxia Guiding (最高人民法院关于北京、上海、广州知识产权法院案件管辖的规定) [Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on the Jurisdiction of the Intellectual Property Courts of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou over Cases]( Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. October 31, 2017, Effective November 3, 2017) CLI.3.237583 (Lawinfochina).

- See id.

- USPTO, IIPI, supra note 28, at 61.

- See id.

- See id. at 60.

- See id. at 62.

- CCCPC, supra note 7.

- Chen Jinchuan, Inside Beijing’s New IP Court, 247 Manging Intell. Prop.10, 13 (2015).

- Zuigao Renmin Fayuan Guanyu Yinfa “Zhishichanquan Fayuan Jishu Diaochaguan Renxuan Gongzuo ZhidaoYijian(Shixing)” (最高人民法院关于印发《知识产权法院技术调查官选任工作指导意见(试行)》) [The Guiding Opinions on Selecting and Appointing Technical Investigator for Intellectual Property Right Courts (for Trial Implementation)] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. August 14, 2017, Effective August 14, 2017) CLI.3.305003 (Lawinfochina).

- Zuigao Renmin Fayuan Guanyu Zhishichanquan Jishudiaochaguan Canyu Susong Huodong Ruogan Wenti Zanxing Guiding) ( 最高人民法院关于知识产权技术调查官参与诉讼活动若干问题的暂行规定) [Interim Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Participation of the Technical Investigators of Intellectual Property Courts in Legal Proceedings] (Promulgated by Sup. People’s Ct. December 31, 2014, Effective December 31, 2014) CLI.3.296203 (Lawinfochina).

- See id.

- Zhang Lingling (张玲玲), Wanshan Woguo Zhishichanquan Fayuan Tixi Chubu Gouxiang(完善我国知识产权法院体系的初步构想) [Thoughts On Improving China IP Judicial Court System], 3 Intellectual Property. 27, 29 (2018).

- Stanford Law School, China’s Case Guidance System: Application and Lessons Learned (Part 1), China Guiding Cases Project (May 3, 2018), https://cgc.law.stanford.edu/guiding-cases-surveys/issue-3/.

- Finder, Susan, China’s Evolving Case Law System in Practice, 9 Tsinghua China L. Rev. 245, 247 (2017).

- Jiang Huiling & Yang Yi (蒋惠岭,杨奕), Beijing Zhishi Chanquan Fayuan: Yi Xian/i Panjue Zhidao Shenpan Gongzuo Zhidu de Chuanxin Shitian ( 北京知识产权法院:以先例判决指导审判工作制度的创新实践) [Beijing Intellectual Property Court: Innovation in System Using Precedents to Guide Adjudication], LEGAL DAILY (April 6, 2016, 14:56 p.m.), http://www.legaldaily.com.cn/fxjy/content/2016-04/06/content_6554635_2.htm.

- Stanford University, Yantaohui Zhaiya: Jianli Zhongguo Xinzhishichanquan Anli Zhidu: Yu Zhongguo Faguan, Falv He Dashuju Zhuanjia Taolun, Stanford Faxueyuan Zhongguo Zhidaoxing Anli Xiangmu (研讨会摘要:建立中国新的知识产权案例制度:与中国法官、法律和大数据专家的讨论,斯坦福法学院中国指导性案例项目,指导性案例研讨会™)[Guiding Cases Seminars], (October 19, 2017) , https://cgc.law.stanford. edu/event/guiding-cases-seminar-20171019.