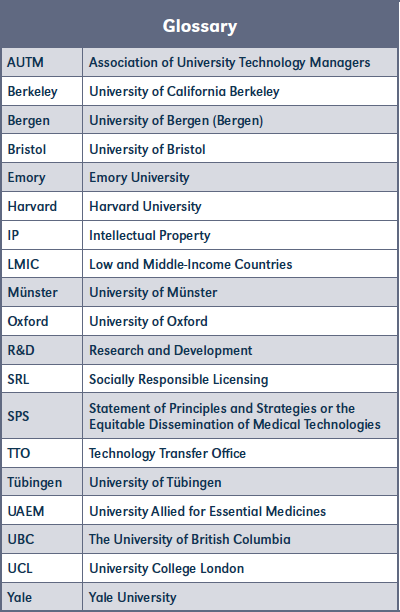

les Nouvelles February 2019 Article of the Month

Recent Experiences In Policy Implementation Of Socially Responsible Licensing In Select Universities Across Europe And North America: Identifying Key Provisions To Promote Global Access To Health Technologies

Faculty of Medicine,

University of Groningen

MD/MSc Candidate (2019),

Groningen, The Netherlands

Faculty of Medicine,

University of Toronto

MD/MSc Candidate (2020),

Toronto (ON), Canada

Ecole des Hautes Etudes en

Sciences Sociales (EHESS),

Centre de recherche, médecine, sciences, santé, santé mentale, société (CERMES3)

PhD Candidate,

Paris, France

Abstract

Introduction

Intellectual property (IP) management at universities and public research institutions (PRIs) has the potential to enable or restrict access to university-derived health technologies in all countries, but most notably low-resource settings. Given their fundamental role in research, as well as their responsibility to prioritize public interests in research and innovation, several leading universities across the United States, Canada and Europe have adopted socially responsible licensing (SRL) policies for the industrial development of their biomedical research.

This study aimed to:

- Assemble experiences of universities and their Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) in implementing SRL policies, and

- Identify key provisions and clauses adopted within universities' legal frameworks to promote global access to licensed health technologies derived from publicly-funded research.

Methods

In order to assess how universities and PRIs can best manage their IP in accordance with public health objectives, our research team conducted a phenomenological qualitative study that involved a survey of experiences in policy implementation of SRL in select universities. Our methodology consisted of semi-structured interviews with licensing officers at TTOs of nine universities including Harvard, Yale, and Oxford.

Between September and December 2015, questionnaires were designed, and conducted with technology transfer officers from nine universities that implemented an SRL policy. These universities are located across United States, Canada and Europe.

Significant Findings

We found that all of these universities were able to develop their own SRL policies with specific aims around promoting societal impact of university-derived health innovations and promote equitable distribution of these technologies in low-and middle-income countries. Furthermore, our findings showed that the interviewed TTOs have gained experience with incorporating SRL language in contracts with third-party licensees in order to better monitor the downstream development of their intellectual property and to ensure it benefits public health. We identified several SRL terms and provisions incorporated by TTOs into licensing agreements with industry partners to ensure global access of their health technologies. These provisions were noted under the following sections of licensing agreement contracts: Recitals, Definitions, Exclusive vs. Non-exclusive Licensing Requirements, Royalties, Obligations of Parties, and Breach and Termination.

Noteworthy examples of equity-based contractual obligations and provisions to promote global access included: university's right to require due diligence in downstream development, monitoring licensee's product development plan, licensee's obligation to sell final products at-cost, licensee's obligation to secure global access provisions in sublicenses, and licensee's concurrence that the university will not file patents in LMICs, and the licensee's agreement to not pursue infringement action in developing countries.

Conclusion

Our findings show that, by implementing an SRL policy, universities strengthen their ability to incorporate global access provisions into licensing agreements with industry partners. Significantly, these results were presented at the recent United Nations High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines in 2016 and incorporated into the Panel's final report under section 2.6.2: 'intellectual property generated from publicly-funded research'. This reflects an ethical awareness and willingness on the part of these institutions to align their IP management practices with public health targets to facilitate access to the end product health technology in low-resource settings. However, there remains an overall lack of guidance for universities and PRIs worldwide regarding successful implementation of socially responsible IP management and licensing practices. Therefore, we hope that dissemination of current SRL policies and sharing of experiences across institutions will promote recognition and widespread adoption of equity-based provisions and formal SRL policies for technology transfer of publicly-derived health technologies across universities and PRIs worldwide.

Introduction

Publicly-funded research is an indispensable component of the biomedical research and development (R&D) process. Universities have the responsibility to prioritize the public interest, notably by ensuring that outcomes of medical research are available to people around the world. Over the past few decades national policies, mostly inspired in the U.S. Bayh-Dole Act, have encouraged universities to seek broad patent protection of results of publicly-funded research in order to induce innovation.1 Consequently, several universities in countries around the world have reacted to such incentives by expanding the licensing of their Intellectual Property (IP) rights to the private sector regardless of their impact in guaranteeing further access to university-derived health technologies.2,3 There is, however, a growing shift in culture among universities and PRIs with respect to recognition of the ethical and social responsibility surrounding the management of IP resulting from publicly-funded research. 4 As such, a handful of these universities have begun to establish internal policies and procedures aimed at licensing their IP rights in a socially responsible manner and thereby ensuring the social return of public investments.

In 2010, universities owned patents on nearly one in five drugs that were on the market in three major areas— infectious diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and Alzheimer's disease. As universities and PRIs are proactively engaging in patenting their health inventions and monitoring the social impact of their licensing practices, it is crucial to help them meet their social responsibility.5 According to such institutions that have committed to endorse this cultural shift in IP licensing, this practice has been referred to as socially responsible licensing (SRL), global access licensing and equitable licensing. This article uses the term SRL to refer to a broad set of approaches to IP licensing that includes any attempt to safeguard access to the end product, regardless of the extent of protection that they ultimately provide.

One of the first noteworthy cases highlighting the need for SRL at universities took place in 2001, after a group of Yale University law students, together with Médecins Sans Frontières, helped convince Yale and Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) to allow generic production of Yale-discovered Stavudine in sub-Saharan Africa. The renegotiation of the university license with BMS led to a 30-fold price reduction of the drug.6 Since 2001, SRL practices have evolved at the university-level. In 2007, the Statement of Principles and Strategies for the Equitable Dissemination of Medical Technologies (SPS), a document that outlines a series of goals and licensing practices, was put forward by the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM) and six universities from within the United States to advance progress in health in developing countries.7

When SRL is adopted as part of a formal university IP policy, the result is strikingly different. In 2008, Dr. Kishor M Wasan, a professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC), developed an oral formulation of Amphotericin B, a novel agent against Leishmaniasis. This was the first technology where the rights to commercialization were licensed using UBC's Global Access Principles, an SRL policy adopted by the University Industry Liaison Office at UBC in 2007. In return for rights to develop and sell the drug for bloodborne fungal infections in the developed world, iCo Therapeutics agreed to produce and distribute the drug at-cost for treating leishmaniasis in the developing world. These institutional experiences have shown that universities can gain leverage in influencing global equitable marketing of health products by implementing SRL practices in the upstream stage of technology development.8 As a result, universities can actively engage in the promotion of patients' equal and affordable access to the health technologies that they contributed to discover and develop.

The manner in which universities manage their IP rights can enable or restrict access to publicly funded health technologies for populations around the world. Over the past few years, some IP management practices have created barriers impacting patient's access to lifesaving medicines.9 Consequently, many universities have invested in efforts to significantly change their licensing practices. However, it is unclear how the implementation of universities' SRL policies have evolved over the years and how this implementation has impacted the licensing practices of Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs). This study aims to:

- Assemble experiences of universities and their TTOs in implementing SRL policies, and

- Identify key provisions adopted within universities' legal framework to promote global access to health technologies.

Materials and Methods

For the purpose of this qualitative study, we took a pragmatic perspective and utilized phenomenological methodology. From September to December 2015, the authors of this article and students from Universities Allied for Essential Medicines (UAEM) conducted interviews with TTO officers from universities that implemented an SRL policy. The inclusion criteria for selecting universities were the following:

- Universities that had formally adopted or implemented an SRL policy prior to September 2015;

- Universities that had more than one year of experience with SRL policy implementation; and

- Universities with TTO officers that were available for an online interview or where UAEM students were present and able to conduct the interview.

From this initial criterion, 11 universities were identified and contacted:

- Canada: The University of British Columbia (UBC);

- Europe: University of Bergen (Bergen), University of Bristol (Bristol), University College London (UCL), University of Münster (Münster), University of Oxford (Oxford), and University of Tübingen (Tübingen); and

- United States: University of California Berkeley (Berkeley), Emory University (Emory), Harvard University (Harvard), and Yale University (Yale).

Using a questionnaire, the TTOs' experiences in the following areas were explored in this study: (Appendix 1)

- Goals and Principles of SRL policies at the universities; and

- SRL terms, provisions and clauses included in contracts negotiated by the TTO.

For the qualitative analysis, the data collected was assembled, and topics were identified according to its relevance for the study's aims. The data was then categorized according to identified topics from interviews with TTO officers. Sentences and expressions written with quotation marks and in italics refer to the original wording consulted and extracted from a diversified range of sources such as interviews, contracts, SRL policies, unpublished documents, and website information from universities. The term Low and Middle- Income Countries (LMICs), as used in this article, should be generally interpreted according to the definition of the World Bank Atlas method.10 However, when mentioned in the results section as part of the data collected from interviewed universities, LMICs should be interpreted according to the definition adopted by each university in their own terms.

With regards to how our questionnaire was structured, it is important to stress that interviewees were invited to openly describe the SRL language they have used in their contracts since the implementation of the respective policy. Therefore, when outlining the language they have used, interviewees did not describe the terms exhaustively. Furthermore, when the use of any particular term or language is attributed to a certain TTO, it is not inferred that this particular TTO is the only one to adopt such a strategy.

Results

Baseline Information:

From an initial selection of 11 universities worldwide with an established SRL policy, we interviewed nine TTOs across Canada, Europe, and the United States. Münster and Tübingen fulfilled the inclusion criteria but were not included in this study due to lack of contact with the TTO representatives. The following universities were included in the final selection: UBC, Bergen, Bristol, UCL, Oxford, Berkeley, Emory, Harvard, and Yale. See Figure 1.

Universities developed different strategies to implement their SRL policy. Berkeley, Emory, Bristol, UBC, UCL, and Bergen adopted an internal set of rules, while Yale and Harvard have both guided their internal licensing practices through the development and endorsement of the SPS. UBC adopted both strategies, making the case for a strategy in which the internal adoption of a set of principles was also strengthened by the signature of the SPS.

Our findings regarding universities' experiences with implementing their SRL policies are presented in a sequential process by firstly identifying their aims, strategies and principles, and then followed by more specific legal terms and provisions they utilize in contracts with industry partners. With respect to outlining these specific terms and provisions that promote global access of health technologies, we present our results in the standard structure of a license contract with the following sections: recitals, definitions, license grant, obligations of the parties, and termination of the contract.

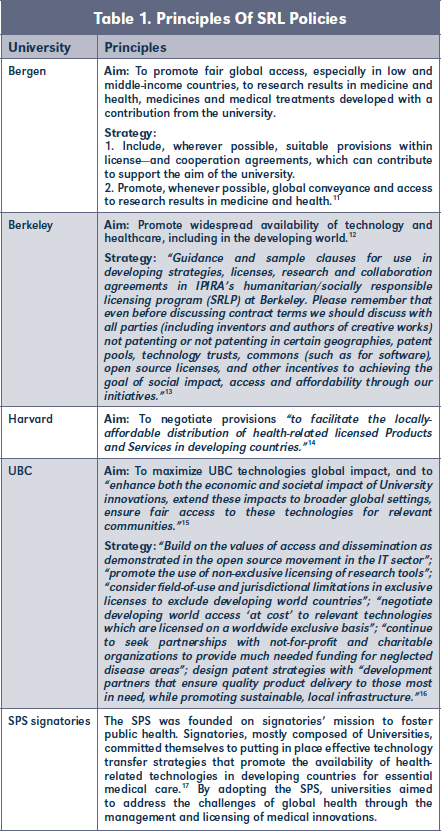

- Principles of SRL Policies at the Universities

Universities developed their SRL policies with various aims and strategies in mind. The main difference between the aims and strategies was which countries should benefit from the developed health technologies (Table 1). Not only is it possible to identify different justifications for implementing SRL policies, but also specific perspectives on how to shape them.

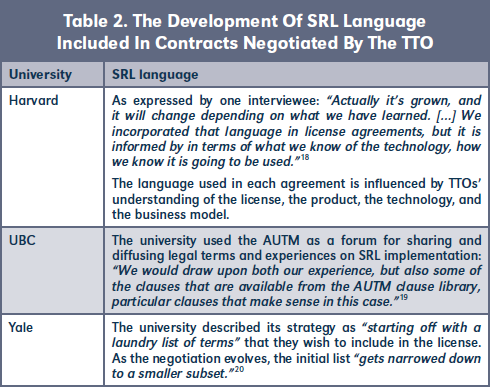

- SRL Terms Included in Contracts Negotiated by the TTO

Implementing SRL policies through the strategic management of universities' IP can imply a process of learning the adequate legal language for each particular situation. Although there doesn't seem to be a standard set of language and terminology for SRL, we outline various examples of SRL language used in our studied universities in Table 2.

Yale University described its strategy as "starting off with a laundry list of terms" that they wish to include in the license. As the negotiation evolves, the initial list "gets narrowed down to a smaller subset."20

As mentioned by the UBC TTO, the AUTM Global Health toolkit has been a relevant source providing experts examples of SRL language to be incorporated into license agreements signed by the university.21

More specific language will usually take shape as the TTO and industrial partner integrate the social context in which the finished technology will be commercialized. Technology management is complex and is associated with vast possibilities of languages to solve a particular issue.22 The following section depicts an overview of key SRL terms that appeared in our survey, without addressing them exhaustively.

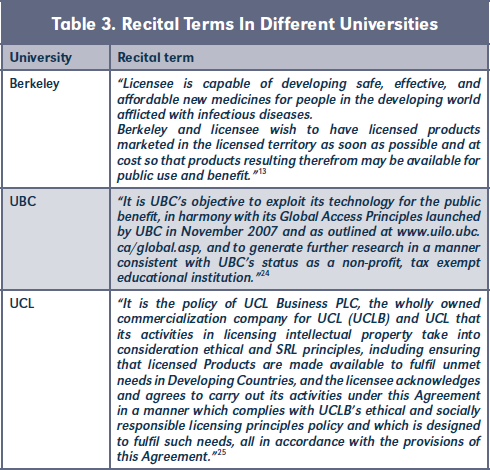

A. Recitals

Recital terms were used to translate and emphasize universities' SRL policy commitments within contracts negotiated by the TTO.23 (Table 3)

B. Definitions

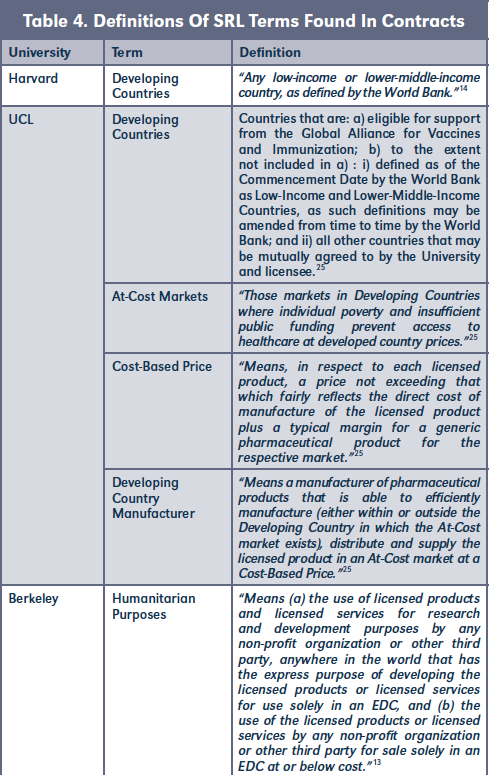

SRL contracts often define specific conditions for different countries. Therefore, it is important to outline these definitions in order to avoid misunderstanding.23 Some key definitions found in our study, such as "Developing Countries," or "Humanitarian Purposes," were used by the universities as part of their SRL strategy. See Table 4. As for the definition of "Developing Countries," Harvard and UCL are using the definition of the World Bank.

C. Promoting SRL Principles in Exclusive Licenses

A license can be delivered by the university-licensor according to different scopes of IP distribution. Licensors can grant an exclusive license, excluding the use of the licensed IP to everyone but the licensee, after which the Licensor stays limited to use its IP. A license can also be granted as a sole license, through which the licensee receives exclusively the right to use the licensed IP, however the Licensor keeps the right to use its licensed IP. And finally, the Licensor can grant a license non-exclusively, retaining the right to license its IP as many licenses as it wants. Some of the interviewees mentioned having signed exclusive licenses with industrial partners, while at the same time defending their SRL policy. See Table 5.

D. Royalties

Even though royalties on drug sales may represent a part of universities' revenues, some TTOs revealed the practice of reducing royalty rate for sales of licensed products in LMICs. This practice would most likely reduce and, therefore, achieve the goal of lowering the cost of health technologies in LMICs.23 See Table 6.

E. Obligations of the Parties E.1. University's Right to Require Due Diligence

Universities affirmed requiring that licensees seek "diligent efforts" in making licensed products available at locally-affordable prices in developing countries. It was identified through UCL's SRL strategy that diligent efforts can imply "diligent efforts to develop the licensed product," as well as "diligent efforts to commercially exploit licensed products."

According to UCLB's ethical and socially responsible licensing policy, licensees must undertake "Diligent Efforts" to supply the licensed products to customers" in "At-Cost Markets" at a "Cost-Based Price" in a manner to meet market demand for the licensed products. In this sense, UCLB would define "Cost-Based Price" regarding the licensed product as "a price not exceeding that which fairly reflects the direct cost of manufacture of the licensed product plus a typical margin for a generic pharmaceutical product for the respective Market." If the licensee is unable to supply the licensed product at a Cost-Based Price in any At-Cost market or is unable to "meet the market demand" for the licensed products in those markets, UCLB would require licensees to "use diligent efforts" to sub-license the resulting invention to one or more Developing Countries Manufacturers.

E.2. Monitoring Licensee's Product Development Plan

Universities have emphasized the need for maintaining regular contact on the licensee's diligent efforts to develop licensed products, notably by monitoring development steps, and maintaining regular contact with licensees. See Table 7.

E.3. Licensee's Obligation to Sell Final Products at Cost

One of the terms adopted by interviewed universities involved the obligation of the licensee to sell the final product at-cost. Yale's SRL policy stated their aim to get "licensees to agree that they will offer their licensed products at-cost in LMICs." The university also sought to apply more specific obligations, such as with one licensee, stipulating: "whereby if they set a price of X in major market countries, they commit to selling these products for no more than 25 percent of X in LMICs."20 Berkeley specified the following: "We have patent rights in LMICs or countries defined in any other way such as Economically Disadvantaged Countries or listed in an Appendix, the licensees are required either to sell the product for free or at cost."27

E.4 Licensee's Obligation to Secure Global Access Provisions in Sublicenses

Another term incorporated in licensing agreements is the obligation for Licensees to secure global access provisions in sublicenses with any third-party companies. In this sense, UCL's General Diligence terms include a requirement for "all sub-licensees and other parties involved in the development and commercial exploitation of licensed products to agree in writing to comply with the principles found in UCLB's ethical and socially responsible licensing policy."25) Similarly, Berkeley states that their licensees are required to "reserve their global access rights and obligations in the university's arrangement as they move forward" with subsequent licensing to other companies.27

E.5. Licensee's Concurrence that the University Will Not File Patents in LMICs

Several TTOs sought to include terms safeguarding universities' prerogative to not file universities' patents in LMICs. See Table 8.

E.6. Licensee's Agreement to Not Pursue Infringement Action in Developing Countries

Furthermore, some universities have sought to include terms requiring licensees not to pursue infringement action in LMIC settings. In this regard, Harvard specifies that, before the licensee commences an infringement action, they must consider the potential effects of the suit on the locally-affordable availability of licensed products in developing countries. (18) Yale revealed that they are often successful with getting licensees to "agree not to pursue infringers of those patents in the developing world provided that the infringing activity is not intended to export the product back to a major market country." Consequently, if a competitor company wants to produce a product in an LMIC and sell it locally there, the licensee would not take infringement action against them. However, if the competitor company produces in that country and then exports to the United Kingdom, for example, then that would allow the licensee to sue that company.20

F. Breach and Termination

F.1. University's March-in Rights (Step-in Rights)

A major mechanism used to counterbalance the licensee's leverage derived from the exclusivity is to secure universities' march-in-rights or step-in-rights, notably when the licensee is not meeting its obligation. Universities have mentioned different mechanisms to implement march-in rights such as converting an exclusive license into a non-exclusive license or granting sublicenses to a third party.23 See Table 9.

F.2. Terminating the License

Emory cited that they retained the right to terminate an agreement if a licensee is not adequately developing the technology (material breach) or if a licensee is not adhering to the global access clause. According to Yale's experience, all global access terms are part of the university's license agreements' due diligence provisions. Thus, a failure to uphold any of these provisions can be considered a breach of the contract.20)

Discussion

The main objective of the study was to assemble experiences of universities and their TTOs in implementing SRL policies by identifying key provisions universities have adopted in order to promote global access to health technologies.

In their efforts to implement SRL policies, TTOs have used and created contractual language in accordance to specific technologies and contexts. Most interviewees have argued that the use of a standard language as a starting point for all contracts would be counterproductive and would lead to the inclusion of terminology that would not necessarily be used at the end of the long and uncertain path of technology development. Similarly, Mimura identified that contracts must be innovative and should evolve according to the industry-university partnership landscape.13 The latter stressed the importance of communicating and understanding the underlying research and the ideal outcome before drafting the contracts, notably since the essential terms are sometimes devised and set in the research and/or collaboration agreement that precedes invention and invention/IP licensing. Flowing down the rights through sublicensing has been an important strategy. In addition to tailored IP-approaches, the specialized literature also stresses the need for new business models in order to address the R&D crisis where the market has failed. Recently, new collaboration models have arisen that deserve the attention of research universities and PRIs.29

During the past years, notably since the 2009 Statement of Principles and Strategies for the Equitable Dissemination of Medical Technologies, North American universities have shared experiences on how to develop adequate contract clauses using SRL policies. In this regard, the AUTM was mentioned as a major forum for sharing experiences and diffusing legal terms among TTOs.21 This is particularly important because, throughout the process of technological development, TTOs constantly need to negotiate and draft contracts, such as R&D agreements and licenses. Being immersed in an environment of professionals with different levels of experience on SRL implementation helps to empower TTOs and educate their experts to use contracts as effective instruments for social change to benefit public health. In this sense, Mimura emphasized that "scrupulous drafting and unambiguous definitions" are important to preserve options for the university's institutional mission.13

We have found that when granting licenses on the university's IP, most TTOs would seek to negotiate with companies regarding access to the derived health technologies for LMICs. In the case of exclusive licenses, IP management aligned with an SRL strategy could contribute to counterbalance the negative effects that exclusivity might have on limiting access to the future technology at affordable prices. It is important to further explore in which conditions patent pools and non-exclusive licenses could result in an effective incentive for drug discovery and as a way to maximize early stage competition and access to university derived end-product technologies.

Consistent with universities' identified strategies to implement SRL principles was the practice of reducing royalty rates for products sold in LMICs, an example being the proactive application of a zero percent royalty rate. Although reduction of royalty rates would initially indicate less revenues for universities, we have seen technology managers witnessing positive experiences from such practices. For instance, technology managers from Berkeley identified that, by abstaining royalty payments on sales in defined regions on certain contracts, the university's Socially Responsible Licensing Program has contributed to stimulate and support investment by licensees and philanthropic foundations with humanitarian goals.13 This strategy is comparable to what the research and development organization Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative has implemented through its IP policy by publicly stating that it will not seek to finance its research and operations through IP revenues, even while recognizing that the suppression of royalty rate is not always possible. 31 We have also seen TTOs requiring licensees to uphold contractual obligations of due diligence. This strategy has constituted a mechanism for universities to leverage their authority over their IP rights in order to regulate the conditions of technology development and the end-product marketing. An example of this can be found in the Berkeley TTO strategy of requiring diligent commercialization efforts of the licensed rights in the licensed field of use, and in sufficient quantities to meet the market demand.13

The request of a product development plan also contributes to enforce universities' role in guaranteeing access to health technologies. Although not a first-line SRL provision, the strategy of requesting a plan and actively following up the product development could contribute to strengthen universities' leverage in monitoring access of health technologies. This could be particularly relevant to identify situations in which a company would be granted an exclusive license to develop an invention and then stop or block the development in order to prioritize its commercial strategy.32 Universities can further request licensees to follow through with global access provisions in sublicenses with sublicensed third-party companies. Taking an empirical example, in order to meet the market demand, UCLB has adopted a provision requiring licensees to sub-license the developed technology in LMICs. By stimulating the transfer of the universities' derived IP with developing countries, such a provision can contribute to strengthen local manufacturers' capacities to produce generic and affordable versions of the health technologies for local populations. However, further research is needed to understand the context in which sublicenses are designed by licensees, and how their business models can help guarantee global access. There are other relevant aspects that TTOs should be encouraged to consider when evaluating the public health benefit of license agreements. Among those, Beyer has stressed the importance to address within contracts issues regarding "the access to data necessary to obtain regulatory approval, the right to supply outside the territory in case of compulsory licenses, as well as the freedom to combine the licensed products with other products for the production of fixed dose combinations."33

Additionally, several TTOs require licensees to not file the universities' respective patents or not pursue infringement actions in LMICs as part of their licensing agreement provisions. Such strategies were identified by Beyer as non-assert declarations or non-assertion covenants, and immunity-from-suit agreements. To avoid conflicts in the execution of such provisions, the author recommended that the scope of the agreements and the explicit set of conditions should be clearly defined. In this sense, universities should be attentive to describe in their contracts what licensee actions are permitted and which are the designated territories where the patent owner engages not to enforce their patent rights.33 When discussing limitations regarding universities' reduced leverage in some projects that are less attractive for the industry, Mimura has stressed the importance of safeguarding the licensees' concurrence that the university will not file patents in LMICs, while simultaneously striving to find a plausible combination of incentives and the right partnering structure.13

Universities have mentioned the strategy of including march-in-rights in license agreements in order to protect public health interests, thereby preserving the right to convert an exclusive license into a non-exclusive license if the licensee fails to meet its obligation. At the policy level, march-in rights have been incorporated in the Bayh-Dole Act as a way to enable the U.S. government to intercede in exclusive license contracts generated in relation to products originated from public financial support. Treasure et al. stressed that, while the use of march-in rights by governments as a way to address the cost of health care products developed from public funding revealed to be unfruitful, march-in rights could be used "for cases in which a government-sponsored technology is licensed and then intentionally undeveloped, or for help in extracting minor concessions from licensees in extreme circumstances." 32 In fact, we have no knowledge of concrete cases where universities have activated march-in rights included in a license agreement. Consequently, more research is needed to understand the uses of march-in rights and the challenges of implementing them.

Considering the public relevance of the subject matter, further research is needed in order to:

- Widen the geographical scope of the survey;

- Investigate more broadly and beyond SRL provisions and explore universities' strategies and challenges regarding implementation of global access provisions for health technologies and medicines; and

- Explore universities' and PRIs' local strategies to achieve access to medicines in light of the institutional and national policy environment under which they are regulated.

Limitations

The main limitations of this study are the limited sample size and the restricted geographical scope of selected universities, as most of the participant universities are located in Common Law countries. It should be acknowledged that IP practices related to 'responsible licensing' may be conducted differently under Common Law compared to other legal systems.34 Furthermore, our interviews have not considered the national policy environment in which SRL institutional policies have been locally shaped. For example, the institutional set-up for universities and the cultural embeddedness is very different for universities in the UK compared to their colleagues in the U.S. Another limitation relates to the study's narrow focus on the universities' SRL policy implementation, which is just one out of many aspects of IP management influencing access to public research. Nevertheless, the results contributed to elucidating several points of discussion regarding universities' experiences with adoption and implementation of a formal SRL policy with respect to health technologies.

Conclusion

Given their fundamental role in the health R&D process and their responsibility to prioritize the public interest, several universities and PRIs have established socially responsible licensing policies for the industrial development of their health research.

Leading universities in Canada, Europe and the United States have adopted an SRL policy and, as a result, gained experience with including SRL language in contracts in order to better monitor their IP rights and to benefit public health. Our findings show that universities strengthen their ability to incorporate global access provisions into licensing agreements with industry partners by adopting and implementing such SRL policies. This reflects an ethical awareness and willingness on the part of these institutions to align their IP management practices with public health targets to facilitate access to the end product health technology in low-resource settings. Importantly, these findings were highlighted by the United Nations High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines in 2016 and incorporated into the Panel's final report under section 2.6.2: 'intellectual property generated from publicly-funded research.'

However, there still remains an overall lack of guidance for universities and PRIs worldwide regarding successful implementation of socially responsible IP management and licensing practices. Therefore, we hope that dissemination of current SRL policies and sharing of experiences across institutions will promote recognition and widespread adoption of equity-based provisions and formal SRL policies for technology transfer of publicly-derived health technologies across universities and PRIs worldwide.

By leveraging their ownership rights and managing their IP in a socially responsible manner, universities and PRIs can address the legal barriers to global access of health-related technologies posed by patents and data exclusivity. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=3218516

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted on a voluntary basis. We would like to thank Professor Vertinsky Liza and our UAEM colleagues (Friha Aftab, M.D., Dr. Dzintars Gotham, Angela Ji, Nina le Dous, Karolina Maciag, Kalie Elizabeth Richardson) for helping us contact the TTO officers and/or conduct the interviews with the various universities and TTOs. We thank Whitten, Carolyn and Fendel, Lukas for the guidance throughout this study. We would also like to thank Professor Christine Godt, Dr. Christian Wagner-Ahlfs, Priscilla Li Ying, Dr. Dzintars Gotham, and Nina le Dous, for comments that greatly improved the manuscript, although any errors are our own and should not tarnish the responsibility of these esteemed persons. Lastly, we would like to thank our interviewed TTO officers who took the time to answer our questions.

Supporting Information (Appendix 1)

S1 File. Questionnaire Template for the Interviews With TTOs:

In this study we have analysed Section I Baseline information. Sections II and III of the questionnaire regarding the main challenges that TTOs and universities encounter when implementing their SRL policy will be discussed in a separate article.

- Baseline Information (Factual Information About Practices):

- Does the university have a socially responsible licensing policy and when was it adopted?

- Yes / No

- Date of when it was adopted:

- Link to the policy in our folder:

- What are the clauses and specific terms the TTO uses when implementing their SRL policies in licensing agreements? (please insert quotes and/ or links to documents)

- Quantitative information about licenses (this information might have been given during the interview or in written documents. If not, check if it can be found on their website. Make sure to indicate if the percentage is out of total licenses or just licenses for health technologies and over which period of time. Zero is also information to mention.

- Number of licenses issued since the date of SRL policy adoption: (#)

- What estimated proportion of licenses contained some kind of access clauses?

- Estimated proportion of licenses for which the funding was public? Private? – Estimated proportion of licensees which were known to be for-profit? Not-for-profit?

- Suggest national surveys for monitoring the percentage of universities implementing SRL policies.

- Does the TTO follow up/monitor companies after they were given the license?

- Yes/No

- If yes, by which mechanism? (insert quote from interview)

- Any mention of SRL-type requirements in research grant contracts (e.g. Welcome/UK, NIH/U.S., Gates/other foundations)?

- Perceptions of TTOs About Global Access License— Feasibility, Barriers, Needs, Opportunities (Please insert exact quotes only):

- What were the perceived barriers to implementation, if any mentioned:

- What specific guidance did the TTOs identify as requisite in policies on licensing (if any mentioned)?

- What needs/requirements were mentioned by TTOs to help implement?

- What were the perceived opportunities?

- Is the policy perceived as a threat to the university's income?

- Is the policy perceived as a threat to securing licensing agreements?

- Does the TTO Mention Any of Their Own/What They Consider to be Best Practices? If so, Which? (Insert quotes or links to documents)

References

- Boettiger S. and Bennet A., "Bayh Dole: If We Knew Then What We Know Now." Nature Biotechnology. 2006 Mar; 24 (3): 320-323.

- Mimura C., "Technology Licensing for the Benefit of the Developing World: UC Berkeley's Socially Responsible Licensing Program." Journal of the Association of University Technology Managers, 2006, p. 1528.

- Heller M. A., Eisenberg R. S., "Can Patents Deter Innovation? The Anticommons in Biomedical Research." Science. 1998 May; 280: 698-701.

- Kapczynski A., Chaifetz S., Benkler Y., Katz Z., "Addressing Global Health Inequities: An Open Licensing Approach for University Innovations." Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 2005; 20.

- Reuters T., "The Changing Role of Chemistry in Drug Discovery." International Year of Chemistry 2011, p. 13.

- Universities Allied for Essential Medicines. History. Available via: http://www.uaem.org/who-we-are/ history/.

- Harvard. Statement of Principles and Strategies for the Equitable Dissemination of Medical Technologies [internet]. Available from: http://otd.harvard.edu/upload/ files/Global_Access_Statement_of_Principles.pdf.

- Mimura C., "Technology Licensing for the Benefit of the Developing World: UC Berkeley's Socially Responsible Licensing Program." Journal of the Association of university Technology Managers. 2016. Volume XVIII Number 2.

- UN Secretary-General and Co-Chairs of the High-Level Panel. The United Nations Secretary-General's High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines Report: Promoting innovation and access to health technologies. 2016 sept; p. 26-27.

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups [internet]. The World Bank; 2017. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/ articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lendinggroups. Accessed in 2017, August.

- Principles for fair global access to medicines and medical treatment resulting from commercialisation of medical and health research. Bergen University. 2013 Jan.

- Intellectual Property & Industry Research Alliances (IPIRA). Socially Responsible Licensing at U.C. Berkeley [internet]. IPIRA. Available from: http://ipira. berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/shared/docs/SRLP_Highlights_ 100910.pdf.

- Mimura C., "Memo" [internet]. IPIRA. Updated 2010 Aug. Available from: http://ipira.berkeley.edu/sites/default/ files/shared/docs/SRLP_Guidance_percent26_Clauses_ v100817.pdf.

- TTO of Harvard. A table reporting on the status of deals containing SRL provisions.

- The University of British Columbia (UBC). UBC Global Access Principles [internet]. UBC. Available from: https://uilo.ubc.ca/technology-transfer/ubc-global- access-principles.

- UBC University-Industry Liaison. Principles for Global Access to UBC Technologies [internet]. McGill University; 2007. Available from: https://www.mcgill.ca/ senate/files/senate/UBC_Global_Access_Principles.pdf].

- Indiana. Current signatories of the Statement of Principles and Strategies for the Equitable Dissemination of Medical Technologies [internet]. Indiana.edu. Available from http://www.indiana.edu/~ufc/docs/addDocs/ AY12/SPS.pdf.

- Harvard TTO officer. Interview. Harvard. 2015 Dec.

- UBC TTO officer. Interview. UBC. 2015 Nov.

- Yale TTO officer. Interview. Yale. 2015 Dec.

- Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM). Examples of Executed Licenses Clauses [internet]. AUTM Global Health Toolkit; 2012 March. Available from: https://www.autm.net/AUTMMain/media/Advocacy/ Documents/AUTMGHClauseToolkit3-17-12.pdf.

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Successful Technology Licensing, IP Asset Licensing Series [internet]. WIPO; 2015. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/licensing/903/ wipo_pub_903.pdf.

- Cameron DM., Borenstein R. Key Aspects of IP License Agreements. Ogilvy Renault. 2003; p. 7.

- UBC. Collaborative Research Agreement template [internet]. UBC. Available from: https://uilo.ubc. ca/sites/uilo.ubc.ca/files/documents/CRA_non-exclusive. pdf.

- UCL Business PLC (UCLB). Global Access Licensing working from the standard exclusive license template. UCLB; 2015. Most current version: UCL's Statement of principles and strategies for the equitable dissemination of medical technologies. UCLB; 2017.

- Interview. TTO Officer. Emory, 2015 Nov.

- Mimura C., "Nuanced Management of IP Rights: Shaping Industry-University Relationships to Promote Social Impact. Working Within the Boundaries of Intellectual Property," Oxford University Press, 2010 Mar; p. 269-295. Ed. by Rochelle Dreyfuss, Harry First, Diane Zimmerman.

- University of Oxford (OX). Marketing, confidentiality [internet]. OX. Available from: https://innovation. ox.ac.uk/university-members/commercialising-technology/ ip-patents-licenses/marketing-confidentiality/. Accessed in 2015 Dec.

- Collaborative Innovation to Advance Global Health Solutions. Technology and Innovation. 2014. Vol. 16, pp. 99-105. 3

- Gray A. University technology transfer, Universities Allied for Essential Medicines (UAEM) [internet]. UAEM; 2009. Available from: https://uaem.org/ cms/assets/uploads/2013/03/Universities-Allied-for-Essential- Medicines-University-technology-transfer- 2011-04-30.pdf. Accessed in 2017 Aug.

- Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi). DNDi's Intellectual Property Policy. DNDi. Available from: http://www.dndi.org/wp-content/uploads/ 2009/03/ip percent20policy.pdf. Accessed in 2017 Mar.

- Treasure C.L., Avorn J., and Kesselheim A.S. Do March-In Rights Ensure Access to Medical Products Arising From Federally Funded Research? A Qualitative Study. The Milbank Quarterly. 2015; 93 (4): 761-787.

- Beyer, P., "Developing Socially Responsible Intellectual Property Licensing Policies: Non-Exclusive Licensing Initiatives In The Pharmaceutical Sector." Research Handbook on Intellectual Property Licensing. 2013. p. 228-241.