les Nouvelles January 2017 Article of the Month

On The Use Of Preferential Rights In Intellectual Property Agreements

Université Laval

Technology Transfer Officer

Québec, Canada

Abstract

This article reviews the four main types of preferential rights—options, rights of first refusal, rights of first offer and rights of first negotiation—and discusses their use, benefits and limitations in intellectual property agreements.

Introduction

Unilateral preferential rights are contractual obligations that encumber present or future property of the grantor in order to provide flexibility to the grantee.1

Although they are frequently used in agreements, these preferential rights, such as options, rights of first refusal (RoFR), rights of first offer (RoFO) and rights of first negotiation (RoFN) have not been discussed extensively in the context of intellectual property (IP) agreements. This author and many others have observed that there is also significant confusion among practitioners regarding preferential rights, from the benign improper labelling of such rights,2 to the complacent repetitive use of the same standard provision in every agreement,3 to the more alarming general misunderstanding of the properties and use of each type of preferential right.4

The purpose of this article is to properly delineate each preferential right type, highlight their salient features and illustrate the variations within each type. Without going into the details of agreement drafting,5,6 this article will attempt to guide the practitioner in the proper use of preferential rights in IP agreements.

There are many different contexts where preferential rights are needed in relation to intellectual property. In an emerging technology commercialization project, for example, there are many risks (technical, commercial, legal, regulatory, etc.) that may need to be reduced and controlled before a definitive commitment can be made for the market deployment of that technology. Having an option on the technology, for example, would allow the holder7 a period of time to reduce these risks while maintaining access to the technology at a fraction of the cost of licensing or purchasing it.

In the following pages we will discuss the four types of preferential rights, starting with the option, the strongest right for its holder, and ending with the right of first negotiation, the weakest right.

Option

An option is the strongest preferential right as it is the only one that leaves all the control in the hands of the holder.

Definition

An option on an IP asset can be defined as follows: In exchange for a consideration called the option fee, an option gives its holder a right, but no obligation, over an IP asset of the grantor during a defined period of time, the option period, where the option can be exercised at a predetermined price, the exercise price.8 This type of option, the call option,9,10 can either be a provision of an agreement, or an agreement onto itself, in which case it is called an option in gross.11

Constrains on the Grantor

As with any preferential right, the option encumbers the grantor’s property in order to provide flexibility to the grantee. While a purchase option does not automatically restrict the licensing to 3rd parties, it will put at risk these licenses for the grantor until the option lapses. Similarly, a license option does not necessarily mean that the IP cannot be sold but, depending on deal terms, an assignment could be subject to grantee approval. Also, granting a purchase option on an IP asset could prevent the grantor from monetizing a license on that asset or using that asset as collateral for a loan.

Another constrain that can be put on the grantor is the “no shop” provision where the grantor is restrained from offering the IP asset to 3rd parties for the duration of the option. While this hindrance is not implied by the grant of an option it is often added to the option language.

From the general definition above, we will expand on the following: the scope of the right granted, the option period, the option fee and the exercise price.

Scope of the Option Right

The call option either gives the grantee the right, to acquire a license on the IP asset, to purchase the IP asset, or to otherwise modify the terms of a contract. For example, in a license agreement, it can allow the grantee to convert a non-exclusive license into an exclusive licence (or vice versa), to add a new field-of-use, to prolong its term, to include additional territories, to add complimentary IP assets, to buy out or lower the royalty obligations, etc.12

Of particular interest is the case of the license option, where, depending on the specifics of the option grant provision, the exercise can trigger the following:

- The execution of a fully pre-negotiated license agreement;

- The negotiation of a comprehensive license agreement based on a pre-negotiated term sheet; or

- The start of good faith negotiations on a license agreement over a limited time period.

Obviously, the first scenario is ideal in terms of effect clarity but rarely occurs in practice since the parties often use the option to postpone the cost and effort required for a fully negotiated licence agreement. The second scenario is the most practical and the most common because it offers sufficient business certainty without requiring too much time or money. The last scenario can be seen as an agreement to agree, and some authors argue that such a contract could be found unenforceable in some jurisdictions,13 especially if no default mechanism, such as arbitration, is in place in case the parties fail to agree. Furthermore, in our opinion, that last scenario does not constitute an option proper but is akin to a standstill provision 14 coupled with a right of first negotiation, something we will discuss later.

Even if the concepts of exclusivity and rank of the option highlighted in the “special cases” below are unusual, they are, however, important in defining the scope of the option right and need to be discussed, especially in the context of multi-party agreements. For example, if simultaneous multiple unranked non-exclusive options are granted on an exclusive license, the agreements could be structured in a way that the first optionee to exercise gets the license. Furthermore, if these same options were ranked, then the agreement could state that the first optionee to exercise triggers a decision on all other optionees to exercise or not, with the highest ranked exercising optionee benefiting from the exclusive license. Therefore, in order to properly secure its rights on an exclusive license, or an assignment, an option holder should make sure that the agreement language refers to an exclusive or first rank option. The concept of exclusivity, or rank, is irrelevant in the case of non-exclusive licenses and the grantor can simultaneously grant multiple options to non-exclusive licenses without detriment to any of the grantees. Furthermore, the concept of rank can also be used to define the order of priority between different preferential rights. For example, an owner could grant to one party an option to license a patent that is subordinated to another party’s right of first refusal on the same license. However, if the owner initially grants an exclusive option it cannot, for the duration of the option, grant other preferential rights with the same scope and on the same IP asset to other parties.

Option Period

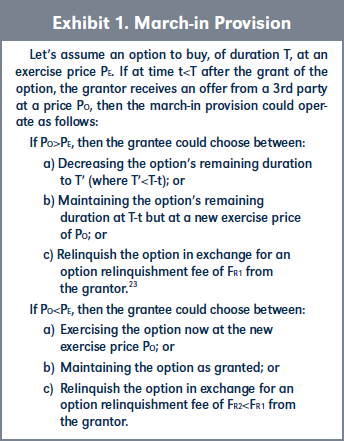

The option period can be defined in many different ways, as the start and end dates can be predetermined or conditional. For instance, a conditional start date can be the filing date of a provisional patent application, while a conditional end date can be one year after the delivery of the final report on a R&D project. Also, performance conditions on either the grantor or the grantee could modify or define the option period. For example, an option could be valid as long as the grantee pays all patent expenses, or the option could last until the grantor builds a proof-of-concept prototype using the optioned technology. The option period could be extended with additional option fee payments by the grantee or terminated early by the grantor with a break-up fee paid to the grantee. The option could also be cut short by a march-in provision15 triggered by a 3rd party offer for the IP asset (see Exhibit 1). Obviously, the grantor should be able to terminate an option, or any preferential right, in case of an uncured default of the grantee. Among others, a patent purchase option should not survive the termination of the overarching patent license agreement. Lastly, it is worth mentioning that in some jurisdictions perpetual options, on top of being detrimental to the grantor, are illegal/not valid.16

Option Fee

The holder should pay a consideration to the grantor in exchange for the control it gets over the IP asset through the option. This is especially true for options in gross where the option fee is not combined with other compensations such as when the option is only a provision of a larger agreement. The option fee can take many forms such as a one-time upfront payment, periodic payments, patent cost reimbursement, R&D funding, other IP rights, etc. The consideration can be fully or partially creditable17 towards the exercise price or not at all. The payments can be guaranteed or conditional on the achievement of milestones such as obtaining a patent or creating a proof of concept prototype.

Most of the time, however, the option provision is part of a larger agreement and the consideration for it is often not discernable from the consideration paid in the overriding agreement.

In general, the following parameters tend to increase the value of the option: duration, underlying IP asset value, option scope, and performance conditions imposed on the grantor. Conversely, if many performance conditions are required of the grantee then, all things being equal, the value of the option is reduced. Betten18 has provided methods to price options based on the principle that they are delays to executed transactions. Therefore, if an executed transaction would represent some net present value (NPV) for the grantor, then the grantee must pay “interest” on that NPV for the duration of the option.

Exercise Price

There are two different ways to establish the exercise price of an option, either set in advance, or established at the time of exercise. When the consideration is predetermined it can be fixed, or fluctuate over time.19 When established at the time of exercise, the consideration can either be computed using a formula, appraised by a previously agreed upon 3rd party, or negotiated by the parties.

Also, some agreements have a provision regarding a termination fee. Termination fees are established on top of, or in place of an option fee, to compensate the grantor for the fact that the non-exercise of the option could cause a devaluation of the IP asset.20

Special Options

The following special options need further discussions: compounded options, bilateral options and options combined with RoFRs.

Compounded options are options that contain other options. For example21 let’s consider a multistage research project to develop a patented technology where the sponsor makes a go/no-go decision after each stage. Initially, the holder has an option on a license, with predetermined terms, for the duration of the first stage of the research project. At the conclusion of each stage, the holder has the option to finance the next stage of the project, thus prolonging the option period, or to abandon the project altogether. As illustrated, the first option contains numerous other options and is thus considered a compounded, or nested, option.

Bilateral options are encountered in agreements in which both the owner and the holder have put and/or call options in overlapping or different time periods. For example, a licensee could have a three-year purchase option on a patent at $3,000,000 while the licensor could have a simultaneous sale option at $750,000.

When an option is combined with an RoFR, the holder, upon the trigger of the RoFR, can decide which right to exercise, notwithstanding anything else in the agreement to the contrary. Whether the option survives, if its not exercised, seems up for debate, as U.S. courts have held in some cases that the option survives, and in others, that it is forfeited.22 A good drafting tip here would be to make sure that the intentions of the parties are explicitly spelled out in agreements where an option and a RoFR co-exist.

As we have seen, options are very flexible instruments that can be tailored by the parties to fit the context of the IP transaction. As we shall see later, they are easier to implement than rights of first refusal and much less likely to induce litigation. While they are more constraining for the grantor, they are also more likely to yield a valuable consideration in return.

Right of First Refusal (RoFR)

While not as constraining as the option, the RoFR still remains a sizable obligation for the grantor and can have a market chilling effect on the value of an IP asset.

Definition

A RoFR can be defined in the following manner: In exchange for a consideration and for a period of

time the right of first refusal, once triggered by a pending agreement within its scope between the grantor and a 3rd party over an IP asset of the grantor, allows the grantee to match the terms of said agreement.

As we shall see below, RoFRs on IP assets pose numerous structuring challenges, and their inclusion in an agreement can literally be a ticking litigation time bomb.

Challenges with RoFRs

A first challenge with the RoFR is the notice to the holder of an offer by a 3rd party suitor. In absence of contract language to the contrary, this notice must present the entire agreement contemplated by the parties in order for the RoFR holder to make an informed decision.24 This is an obvious confidentiality drawback for the 3rd party even if it can remain anonymous. In order to circumvent this problem, the parties could agree that the notice only contain summary terms.

A second problem with the RoFR is the question of what constitutes a trigger event that is a sufficiently complete offer that requires a notice to the right holder. Since the negotiation and agreement drafting costs25 of complete agreements represent a deterrent for 3rd party suitors to submit bids, it is preferable for the grantor to limit offers to term sheets in order to curb those costs. Obviously, there is a trade-off between the reduced cost that a simplified offer provides, and the contractual ambiguity that it creates.

Another issue is the timing of the trigger event as the grantor and the 3rd party could have detailed negotiations, but postpone the trigger event until after the RoFR’s expiry, in order to frustrate the right holder. In such a circumstance, the holder would have a case against the grantor for acting in bad faith.

Yet another concern with the RoFR is the matching of offers. In theory, the holder must match the 3rd party offer on all material terms. But imagine that the entirety or part of the consideration paid by the 3rd party is something other than money, such as unique property. In that case, the holder cannot match the offer and the agreement with the 3rd party is valid, unless the holder demonstrates that this unique property consideration was put in the agreement in bad faith to circumvent the RoFR. Therefore, the wise RoFR holder will structure the agreement so that it has no obligation to match the unique 3rd party property, or that a cash equivalent can be paid instead.

A complication could also stem from lack of clarity in the RoFR scope. For example, let’s say that a research contract has a provision giving the holder a RoFR for a “license” to project inventions. What happens then if a 3rd party wants a non-exclusive license but the holder declines to exercise its RoFR because an exclusive license is desired instead? Is that bad faith on part of the grantor?

Now, let’s say that the RoFR is for an “exclusive license.” What happens if the 3rd party accepts a non-exclusive license on some limited, but relevant to the holder, field-of-use (FoU)? An exclusive licence on another FoU could still be granted to the holder, so is that bad faith on the grantor?

From these examples we can see that the scope of the RoFR must be very clearly defined in terms of exclusivity, FoU, duration and territory. A prudent drafter will add a provision stating the conditions where licenses can be granted to a 3rd party outside of the RoFR scope and that these licenses do not extinguish the RoFR.

Dilemmas can also occur when the conditions on which the RoFR can be renewed have not been considered in the agreement. One such example is when the deal with the 3rd party fails after the RoFR has been waived.26

The question of the exclusion of certain transactions from the exercise of the RoFR needs to be considered in detail. Usual exclusions include deals that occur in litigation settlements, mergers, bankruptcies, or between affiliates.

A final difficulty with RoFRs surrounds the scope of 3rd party transactions. What happens if the transaction between the grantor and the 3rd party concerns an IP asset larger than the one defined in the RoFR? A possible solution would be to have a price allocation mechanism in place. A simpler solution would be to block the grantor from packaging the IP asset with anything else.

As illustrated, RoFR provisions must be carefully drafted in order to avoid the many inherent pitfalls of this preferential right, otherwise litigation may be on our hands down the road.

Risks of RoFRs

A RoFR puts the grantor at risk in many ways. First, it is well-known that RoFRs have a chilling effect on 3rd party bidders. These suitors are less likely to go after an IP asset burdened with a RoFR; balking at the idea of incurring substantial transaction costs without the certitude of securing it in the end.

The grantor also runs the risk of seeing a transaction with a 3rd party halted by a holder’s injunction. It is possible that a 3rd party suitor would sue the grantor if a pending transaction fails to materialize by the grantor’s own fault. Another concern is the performance of the IP agreement. For example, a license with a 3rd party may yield higher total royalties than the same agreement with the holder simply because the holder cannot reach the sales volume of the 3rd party. Finally, the grantor runs the risk of having increased transaction costs since s/he will have to deal with two parties if the holder exercises its RoFR.

RoFR Fee

While RoFR fees are rare, since RoFRs are hard to value and not customary in standalone agreements, it does not mean that RoFRs are without value. The above mentioned market chilling effect tends to reduce the price the holder will have to pay for the IP asset, which is an obvious value to the holder. Also, the holder may be asked by the grantor to waive its RoFR for a fee if the grantor wants to make sure that the deal with the 3rd party will go through. Another source of value is the liability it creates. If the grantor fails to comply with the RoFR, the holder can sue for damages, even if he did not desire to deal for the IP asset in the first place.27

Kahan28 has analysed the value of RoFRs and RoFOs and found that the value of these preferential rights ex ante are a function of the value of the underlying IP asset, the scope of the right, whether the right is a RoFR or a RoFO, the relative bargaining skills of the grantor and the holder, the transactions costs, and the quality of information the holder and the 3rd party have on the IP asset. However, the formulas to compute the value of these preferential rights contain parameters that are difficult to quantify; this limits their usefulness for licensing professionals. It is still interesting to note that RoFRs are always more valuable than RoFOs and that, all other things being equal, the value of a RoFR increases with the transaction costs. Since the transaction costs are substantial in licensing, we can safely conclude that these rights are valuable.

In another economic analysis of the RoFR, Walker’s29 computations seem to indicate that the cost of the RoFR to the grantor represents about a single-digit percentage of the value of the IP asset, or a license to that IP asset.

An interesting way to address the transaction costs would be to introduce in the RoFR provision an exercise fee that takes the form of a compensation to the 3rd party for the exercise of the RoFR by the holder.30 This break-up fee would have the benefit of reducing the chilling effect of the RoFR on 3rd party bidders. Otherwise, the break-up fee could be paid to the grantor as indemnity for the delay and the increased transaction costs.31

Ranking

As with options, it is possible to rank RoFRs in terms of priority; the first ranked grantee would be the first allowed to exercise. If the first ranked grantee does not exercise, then the second ranked grantee would be in line to decide, and so on. It is worth noting that multiple unranked RoFRs cannot be granted for the purchase, or unique32 license of an IP asset without a contract mechanism to deal with the exercise of multiple RoFRs. Such mechanisms could be an auction between the exercising parties; the co-ownership of the IP asset; or the grant of multiple licenses, either non-exclusive, or exclusive, but limited in territory, or FoU.

Variations and Alternatives to the RoFR

Since RoFRs are constraining, grantors could choose to limit their scope to specific 3rd parties, for example competitors of the grantee. In order to avoid them altogether, grantors could resort to less constraining preferential rights, such as RoFOs or RoFNs; warrant that they will not give preferential rights to any other party; pledge that they will not sell or license to specific 3rd parties; or accept to inform the grantee about 3rd party offers.33

For all the above-mentioned reasons, it is this author’s opinion that RoFRs should be avoided in regards to complex IP transactions such as licenses. However, RoFRs for the cash-only purchase of IP assets can be made to work.

Next we finish our tour of preferential rights by discussing rights of first offer and rights of first negotiation.

Right of First Offer (RoFO)

RoFOs are here defined as follows:

For the right’s duration, a RoFO holder has the right to make a first offer to purchase (or license) an IP asset before the grantor can sell (or license) it to a 3rd party.

Here, contrary to a RoFR, there is no need for a 3rd party offer to trigger the right, only the desire of the owner to transact.

It must be noted that in a RoFO the holder only has to make a take it or leave it offer to the grantor, and that there is no subsequent negotiation required.

It is the opinion of many34 that the RoFO must come with a most favored nation (MFN) provision,35,36 otherwise it would be almost inconsequential to the parties. A MFN provision bars a grantor, who has rejected the holder’s bid, from offering the IP asset to a 3rd party on more favorable terms before re-offering it to the holder.37

The MFN provision should define what constitutes more favorable terms, either more favorable considering the agreement globally, which might be very hard to determine even for a simple IP transaction, or more favorable term-by-term.

As RoFOs are rarely done in stand-alone agreements, the consideration for the RoFO is usually not visible. Furthermore, the value of a RoFO to its holder is even lower than that of a RoFR.38 The interested reader can find an in-depth economic analysis of the RoFO that is beyond the scope of this article in a paper by Hua.39

In other versions of the RoFO, the grantor could make the initial offer instead of the holder;40 both parties could make single offers in predetermined order; or the terms could be determined in advance.41

Since a MFN is very similar to a RoFR, we do not recommend the use of RoFOs on licenses.

Right of First Negotiation (RoFN)

Now let’s define the RoFN:

For the right’s duration, a RoFN holder can negotiate, in good faith and for a period of time, the purchase (or license) of an IP asset before the grantor can transact with a 3rd party.

Like a RoFO, the RoFN is triggered by the owner’s willingness to transact.

A RoFN does not give its holder any guarantee that the parties will come to terms and execute an agreement. If the negotiation period has lapsed, or if the negotiation has reached an impasse and no negotiation time-limit has been set, the grantor, in principle, is free to transact with 3rd parties.

It is important to note that the parties must act in good faith during the negotiation, and if the grantor fails to do so, s/he becomes liable to pay damages, including lost profits, to the holder.42

It is worth mentioning that some future agreement terms, such as the consideration, could be settled at the time of the ROFN grant. Therefore, the RoFN could be made to resemble an option, with the only distinction being that the owner is not forced by the grantee to sell or license.

A RoFN can be strengthened by adding to it a MFN provision. The MFN threshold is set by the last offer given by the holder before the end of the negotiation period. Furthermore, a RoFN renewal clause can be added stating that the RoFN is reactivated if an agreement on the IP asset is not reach with a 3rd party within a given time frame after the negotiation period.43 It must be noted that in some jurisdictions, such as the UK and many Commonwealth countries, a RoFN is considered void and unenforceable, but is valid in the United States and in many European countries.44

Discussion

Having reviewed the various types of preferential rights, it is now possible to summarize the benefits they provide to their holders.

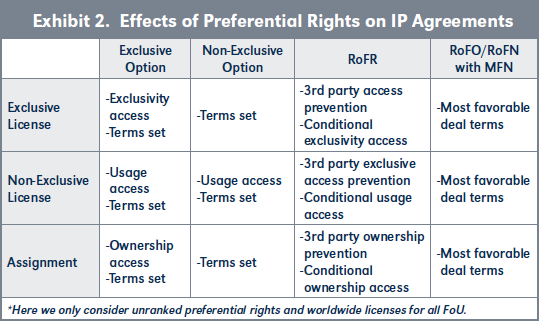

Exhibit 2 presents for the different types of IP agreements, the corresponding benefits of the various preferential rights.

It is important to remind the reader that only options allow the terms to be set in advance, and that only exclusive options guarantee access to the IP asset. RoFRs can be useful to prevent 3rd party access to the IP asset. It must be mentioned that a RoFR on a non-exclusive license provides the possibility of using the IP assets only if the grantor wishes to grant a non-exclusive licence, and does not prevent a 3rd party from having the same access. However, it does prevent the owner from granting exclusive licenses to 3rd parties. Finally, it is worth noting that RoFOs and RoFNs do not provide any surefire effects, unless they include a MFN provision that guarantees the best deal terms.

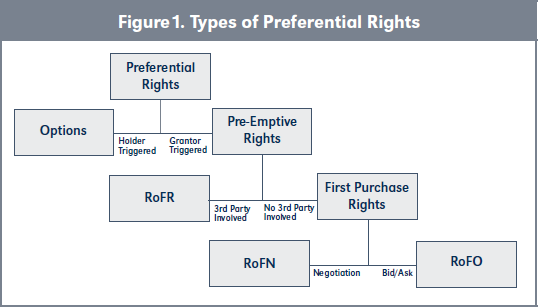

Another way to categorize preferential rights can be made by referring to Figure 1.

Preferential rights can be divided between options and pre-emptive rights—RoFR, RoFO and RoFN. On one side, options are rights triggered by the holder and guarantee access to the IP asset, while pre-emptive rights are triggered by the grantor and are useful in preventing 3rd party access to the given IP asset.

Pre-emptive rights can be further divided into what is here referred to as first purchase rights, RoFO and RoFN, where no 3rd party is involved, and the RoFR where a 3rd party offer is needed to trigger the right.

A final distinction can be made between the RoFN, which requires a negotiation between the grantor and the holder, and the RoFO which does not.

Conclusion

As we have demonstrated, preferential rights provide great contractual freedom for customizing the access to IP assets, however great care must be taken when they are employed as they may do more harm than good if used carelessly. It is also worth noting that further research is needed on the valuation of preferential rights on IP assets, as very few practical models are currently available to dealmakers.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Najat Aattouri of Université Laval, Philippe Boivin of INO and Omar Villasenor of LópezVelarde, Wilson, Hernandez & Barhem, for constructive feedback on the manuscript. The author would also like to thank Jerome Olivier for his invaluable help in the stylistic review of the manuscript.

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN) http://ssrn.com/abstract=2821627

- 1. Bilateral or multilateral preferential rights, such as tag-along/ drag-along rights, or mutual rights of first refusal, also exist in joint property agreements but they will not be discussed here.

- I. L. Hosford, “Options and rights of refusal,” State Bar of Texas 17th annual advanced real estate drafting course, Chapter 11, Dallas TX, March 9-10, 2006.

- R. Houck, “Rights of First Refusal (With Sample Clauses),” The Practical Lawyer, Vol. 55, No. 2, April 2009: 45-54.

- G. G. Gosfield, “A primer on real estate options,” Real Property, Probate and Trust Journal, Vol. 35, No. 1, Spring (2000): 129-195.

- M. Anderson, S. Keevey-Kothari, “Commercialization Agreements: Practical Guidelines in Dealing with Options,” in Intellectual Property Management in Health and Agricultural Innovation: A Handbook of Best Practices, (eds. A. Krattiger, R.T. Mahoney, L. Nelsen, et al.), Vol. II, Ch. 11.7: 1069-1112, (2007).

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Exchanging Value Negotiating Technology Licensing Agreements: A Training Manual, WIPO, 181, January 2005.

- In this article, holder/grantee and owner/grantor are used interchangeably.

- Alternatively referred to as the strike price. For a license option, many more deal terms can be set in advance, in addition to the consideration.

- The opposite of a call option is a put option where the grantee, that is the IP asset owner, is in a position to force the grantor into licensing or purchasing its asset.

- K. Arst, M. Milani, “Derivative Applications for Patent License Agreements,” Patent Strategy & Management, September 2007: 3, 8.

- R. Patkin, “Option, Rights of First Refusal,” les Nouvelles, Vol. X, No. 3, September 1975, 164-184.

- R. Razgaitis, “Valuation and Pricing of Technology-Based Intellectual Property,” John Wiley & Sons, 362, (2003) (see 19-20).

- See note 5, 1075-1076.

- In a standstill provision, the grantor promises the grantee not to license or sell an IP asset to a 3rd party for a given period of time.

- See note 12, 311.

- See note 2, 3-4.

- For example, the consideration can be partially creditable with the creditable portion declining over time.

- P. Betten, “Licensing Option Fee Valuation,” les Nouvelles, Vol. XLI, No. 1, March 2006: 29-33.

- For example, a step-up option is an option where the exercise price increases with time.

- See note 12, 311.

- R. Goldscheider, “The New Companion to Licensing Negotiations,” Clark Boardman Callaghan, 426, (1996).

- M. Scruggs, “Contract Law—Fixed Price Option vs. Right of First Refusal: Construction of a Dual Option Lease—Texaco, Inc. v. Creel,” Campbell Law Review, Vol. 7, No. 3, Summer 1985: 349-367.

- If set in advance, the option relinquishment fee should be much smaller that the option fee. In a more favorable scenario for the holder, it could also be negotiated upon exercise of the march-in provision.

- See note 4, 156.

- These costs are part of the overall transaction costs that also include due diligence costs (technical and legal).

- Some RoFRs are persistent, that is they continue to exist and stay linked to the IP asset even after a transaction with a 3rd party as occurred.

- See note 3, 49.

- M. Kahan, “An Economic Analysis of Rights of First Refusal,” New York University Center for Law and Business, Working Paper #CLB-99-009, 25, June 1999, (http://papers.ssrn.com/ paper.taf?abstract_id=11382).

- D. I. Walker, “Rethinking Rights of First Refusal,” Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance, Vol. 5, No. 1, Spring 1999: 1-58.

- See note 29, 25.

- See note 3, 50.

- By unique license we mean an exclusive worldwide license for all FoUs.

- See note 3, 49-50.

- See note 28, note 39 and note 40.

- L. P Shanda, M. D. Kleinginna, “MFN, Durable Goods Monopoly, And Licensing,” les Nouvelles, Vol. XXVII, No. 2, June 1992: 87-90.

- M.R. McGurk, “Problems of Careless Drafting,” les Nouvelles, Vol. XXXII, No. 3, September 1997: 148-149.

- A MFN right can be perpetual or limited in time.

- See note 28, 3.

- X. Hua, “The right of first offer,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, Vol. 30, No. 4, July 2012: 389-397.

- P. S. Rutter, D. M. Montgomery, “Options, Rights of First Refusal, Rights of First Negotiation and Rights of First Offer: A Guide Through the Maze,” Corporate Real Estate and the Law, Summer 1999, (http://gilchristrutter.com/CM/Articles/Options,% 20Rights%20of%20First%20Refusal.pdf).

- This type of agreement, while having some similarity with the option, is not as constraining since the grantor can choose when to sell or license the IP asset and cannot be forced into it by the holder.

- P. Mendes, “The Economic and Bargaining Implications of Rights of First Refusal and Options to Negotiate,” The Licensing

Journal, Vol. 35, No. 5, May 2015: 4-10.

- See note 40, 3. See note 42, 5-8.