Trends In The Interplay Of IPR And Standards, FRAND Commitments And SEP Litigation

TU Berlin, Fraunhofer FOKUS, Rotterdam School of Management, Chair of Innovation Economics at TU Berlin;

Chair of Standardization at RSM

Berlin, Germany

IPlytics GmbH, TU Berlin and Cerna Mines ParisTech, IP Manager

Berlin, Germany

The Interplay of IPR and Standards Over the Last 20 Years

An uprising issue that became very relevant in the last decades is the role of patents that are essential to a technology standard. Whereas patents are intended to allow its owner to exclude others from using the protected invention, the main objective of standards is to encourage the spread and wide implementation of the standardized technology. Patents that would necessarily be infringed by any implementation or adoption of a standard are called Standard Essential Patents (SEPs). However, the indispensable character of SEPs is worrisome for antitrust authorities, since it may leverage market power and lead to exclusive effects.

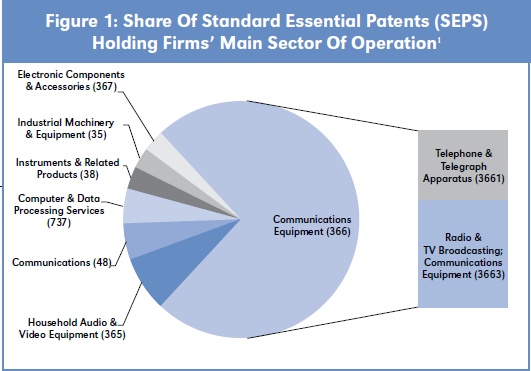

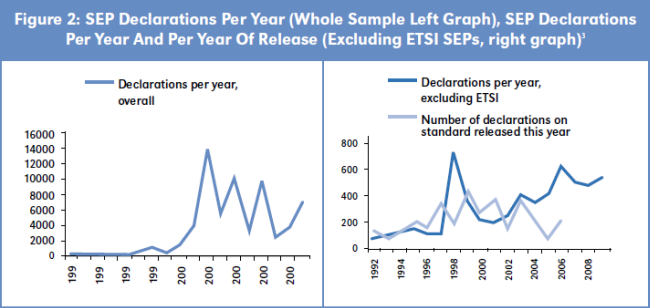

As to a recent study, 95 percent of all publicly declared SEPs can be related to ICT technologies (Figure 1). Over the past twenty years the number of SEPs has been increasing, mainly driven by big standard projects such as GSM, UMTS, LTE, Wifi, Bluetooth or MPEG. Not only the number of SEPs, currently approximately 10,000 active patents (Figure 2), but also the number of SEP holders, approximately 800 entities, has been increasing. Business models of organizations that hold SEPs range from network providers, producing companies, universities or even individuals to Non-Practicing Entities (NPEs) that only provide technologies, but no products. NPEs that only acquire SEPs to license out are often feared to pursue aggressive enforcement strategies and to create situations of patent "hold-up."2

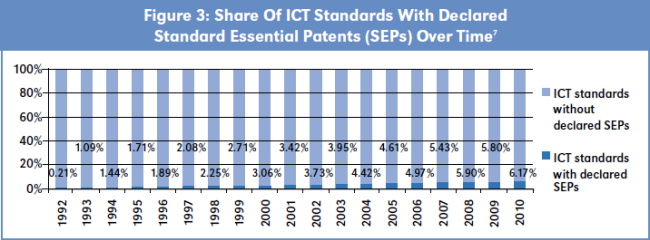

In total over 1,500 standard projects are subject to declared SEPs, mostly set by Standard Setting Organizations (SSOs) such as ETSI, ITU, IEEE, JTC1, ISO/IEC, CENELEC, IETF, OMA or TIA. When comparing the evolution of ICT standards, the share of overall ICT standards subject to declared SEPs has constantly been increasing (Figure 3).

Several studies provide evidence that SEPs are of higher value compared to other patents4 and might positively increase an SEP owner's financial performance.5 Another study shows that SEPs are litigated four times more than other patents, but probability of SEP litigation varies among SSOs.6 These findings suggest that SEPs have a certain strategic value, which may be a reason for the constant increase over the last years (Figure 3).

According to SSO's IP policies all members have to "disclose every specific patent which might be essential to a specific specification before the specification is adopted or amended." Furthermore, SEP declaring firms have to "make a FRAND8 declaration (after the disclosure of the patent but in any event, before the specification is adopted or amended").9 If a firm discloses a patent and refuses to commit on such licensing terms, the SSO will usually try to specify the standard excluding the protected technology. Even though standardization may be accompanied by licensing agreements among many companies, the rules for licensing SEPs are often unclear and can be subject to complex discussions. Therefore, diverging interpretations of FRAND commitments have often been sources of conflict. Very important cases of alleged breach of FRAND commitments have motivated political debates intended to give a concrete meaning to the term "reasonable." Reasonable terms of a license are seen as the maximum amount of royalties a patent holder can ask. "Reasonable" is understood in terms of how much weight the patented technology has compared to other parts that frame the standard or product. If other components of the standard are patented too, a so called cumulative license has to be considered when estimating a "reasonable" license.

Notions on the FRAND System

The notion of firms in standard setting is that FRAND, in general, is a working system, but at the same time may not be a very specific contract. There are many examples of successful license agreements under the framework of FRAND and many examples of successful standard setting projects in light of high numbers of SEPs (GSM, UMTS, WiFi, MPEG, etc.). However, recent challenges due to drastic changes of the ICT business environment increased complexity and debates on the use of FRAND. While standard setting in the early 90's was done by just a few big players that all had similar incentives and business models, the market has changed in recent years. New market participants who own SEPs may not earn money from selling devices anymore, but rather realize returns with patent licensing, advertisement or with constructive software applications. However, new entrants without large patent portfolios are not able to cross license and are often faced with high royalties. It is thus increasingly difficult to define a reasonable license and to determine if requested licensing fees contribute to a technology unit, a technology component or a whole product. Many firms request SSOs to create a common understanding of FRAND, which is very difficult to accomplish. Most SSOs do not intervene in bilateral license negotiation, but support members to clarify IPR rules (ITUT Statement). SSOs often seek to provide a neutral platform and to facilitate discussions on FRAND where all members have equal rights.

However, companies often settle the question of IPR in private governance. Some standard consortia, for example, have ex ante royalty caps (VITA consortium), royalty-free IPR policies (IETF, W3C) or an integrated collective licensing system (Bluetooth, DVB, HDMI). In light of recent litigation on FRAND commitment violation, companies such as Apple, Microsoft, Cisco or Motorola Mobility (Google) have made unilateral commitments on the rate, base, scope and transfer of their SEPs.

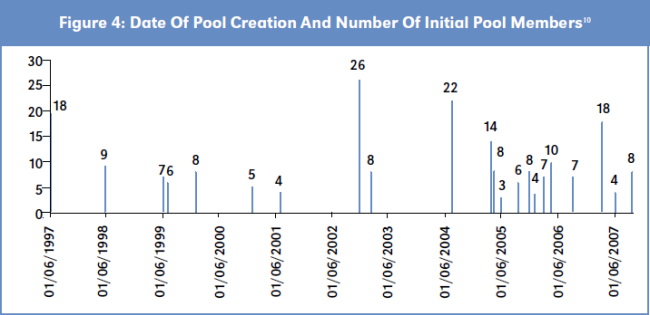

Another IPR coordination mechanism is to pool patents and license them under a single contract. As to the USPTO, a patent pool is "…an agreement between two or more patent owners to license one or more of their patents to one another or third parties." The favorable business review of European and American antitrust authorities in 1997 and 1999 authorized a new model of patent pooling including important safeguards against anti-competitive abuses. Pool patents therefore have to be complementary and necessary for implementing a technology standard. Since the policy change in 1997 the number of patent pool formations has been increasing (Figure 4).

Injunctive Relief and SEPs

A recent discussion deals with the question, if SEP holders should be allowed to impose injunctions on SEPs when possible licensors are not willing to pay a reasonable license. The notion of antitrust authorities (DOJ or the DG competition) is very clear: A FRAND commitment should be a constraint to injunctive relief. SSOs which select patented technologies as an industry wide standard give the right holder a certain market power. In the view of antitrust authorities the market for a SEP license is a market of its own. Thus, SEP holders would have a monopoly position. FRAND is a mechanism to constrain this market power. As to antitrust authorities, someone who commits to license under FRAND and then refuses to license, only requests higher fees. Injunctions would in this case be a vehicle to leverage extensive royalties. The option to impose an injunction could already increase royalties even in the absence of a court decision. These fees would then also be subject to an anticompetitive price. The DOJ and the DG competition believe that circumstances where injunctions are possible should be narrow and only be an option to be imposed for licensees that are not willing to pay at all.

Firms that declare their essential patents to SSOs in most cases do not directly commit to license under FRAND, but only state that they are prepared to grant a license or that they will enter license negotiations in good faith to offer FRAND terms (e.g. as to the ETSI IPR policy). While most U.S. courts would not allow injunctions for SEPs, the situation in Europe is very different (see the injunctive relief decision of a Munich court in the case of Motorola vs. Apple). It seems that there is no legal certainty and courts may decide on a case by case basis. This may even result in different decisions related to the same SEPs across countries. Many firms urge for more precise IPR policies of SSOs to define the willingness to enter license negotiations. However, SSOs fear that some companies would not participate in standard setting, when the enforcement of SEPs is limited upfront.

Possible Reasons for an Increase of SEP Litigation

Recent patent litigation cases that were widely discussed in the media were also subject to SEP. Not only the number of SEP litigation is increasing,11 but also the significance of the litigated technologies becomes more important (e.g. Motorola vs. Microsoft, Apple vs. Samsung). Litigation is very costly for all involved parties and will only be pursued if the technology or product in question has a certain value. One reason of increasing SEP litigation thus is the increasing importance of ICT standards. ICT products increasingly rely on technology standards (e.g. the UMTS, LTE to allow faster Internet connections on smartphones, tablets, notebooks, etc.) to ensure interoperability. Thus technology components often indispensably work together and as a result may even lead to an interrelation of SEPs and non-SEPs.

In recent years, standard setting has evolved from a mere coordination on common specifications to the joint development of complex technology platforms. Firms promote their best and most innovative solution to be accepted as an industry wide standard and SSOs select best quality technologies, i.e. often also patented components. Competition thus also takes place at the standard setting level. Increasing competition may in consequence result in more litigation.

Another reason is the increase of SEPs and the increase of multiple rights holders in general. However, in most cases the increase of SEPs is due to an increase in the number of standards that are subject to SEPs (Figure 3), not to an increase of patents per standard. This means there is an increasing demand for high or even leading edge technology standards in the market, which also increases the possibility of disputes.

A further reason is that SEPs are increasingly transferred due to trades of patents, patent portfolios (Nortel auction) or acquisition of whole companies (Motorola Mobility). Other recent examples are: Ericsson sold SEPs to Research in Motion, Nokia sold SEPs to MOSAID, Sisvel and Vringo, IPcom acquired Robert Bosch SEPs, Highpoint acquired SEPs originating from AT&T, and HTC acquired SEPs from both Google and Hewlett Packard, Acacia acquired SEPs from Adaptix, Intel acquired SEPs from InterDigital, and Apple acquired SEPs from Novell. Intellectual Ventures cooperated with NVIDIA to acquire SEPs from IPWireless. These changes of patent ownership raise legal questions on the transfer of licensing agreements, the entitlement to cover damages, as well as the transfer of FRAND commitments. Firms may find themselves in the position to suddenly pay more for the same patent compared to what they have been paying before the patent transfer. Cases of disagreement may lead to litigation.

The ICT industry is subject to short product life cycles, where market players and market shares have changed in a quick manner in the last ten years. Standard setting as such is a long term process and standards are often implemented over decades. In these cases incumbent firms hold the largest number of SEPs, while their market share decreases. Litigation may thus be subject to a clash of long term versus short term investments.

The main question, however, remains: Is patent litigation just a sign for increasing competition or a sign for future problems due to more complex technologies and patent ownerships, which are threatening the current standardization system?

- Blind, K., Bekkers, R., Dietrich Y., Iversen E., Köhler, F., Müller, B. Pohlmann, T., Smeets, S., Verweijen, J. (2011): "Study on the Interplay between Standards and Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs)" under: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/ policies/european-standards/files/standards_policy/ipr-workshop/ ipr_study_final_report_en.pdf.

- Pohlmann, T.; Opitz, M. (2013): "Typology of the Patent Troll Business," R&D Management, Volume 43, Issue 2, pages 103–120, March 2013.

- Baron, J., Pohlmann, T. (2012): "Patent Pools and Patent Inflation," proceedings of the EARIE - European Association for Research in Industrial Organization- 2012 Conference, under: http://www.webmeets.com/files/papers/ earie/2012/424/Baron%20Pohlmann%20Patent%20Pools.pdf.

- Rysman, M., Simcoe. T. (2008): "Patents and the Performance of Voluntary Standard Setting Organizations," Management Science, 54-11, 1920-1934.

- Blind, K., Neuhäusler, P., Pohlmann, T. (2011): "Standard Essential Patents To Boost Financial Returns," under: http://www. epip.eu/conferences/epip06/papers/Parallel%20Session%20Papers/ BLIND%20Knut.pdf.

- Bekkers, R., Catalini, C., Martinelli, A., & Simcoe, T.: "Intellectual Property Disclosure in Standards Development. Paper at the NBER Conference on Standards, Patents & Innovation, Tucson (AZ).

- Blind, K., Bekkers, R., Dietrich Y., Iversen E., Köhler, F., Müller, B., Pohlmann, T., Smeets, S., Verweijen, J. (2011): "Study on the Interplay between Standards and Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs)," under: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/ policies/european-standards/files/standards_policy/ipr-workshop/ ipr_study_final_report_en.pdf.

- Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discrimnatory.

- The ETSI Rules of Procedure (version of 30. November 2011) Annex 6: ETSI Intellectual Property Rights read in this respect on p. 34 and 35:

- Baron, J., Pohlmann, T. (2012): "Patent Pools and Patent Inflation," proceedings of the EARIE - European Association for Research in Industrial Organization-2012 Conference, under: http://www.webmeets.com/files/papers/earie/2012/424/Baron%20 Pohlmann%20Patent%20Pools.pdf.

- Bekkers, R., Catalini, C., Martinelli, A., & Simcoe, T., "Intellectual Property Disclosure in Standards Development." Paper at the NBER Conference on Standards, Patents & Innovation, Tucson (AZ).