John Carney

Managing Director,

China IP Exchange, LLC, Chair, LES Automotive Industry Advisory Board,

Birmingham, MI U.S.A.

John Carney

Managing Director,

China IP Exchange, LLC, Chair, LES Automotive Industry Advisory Board,

Birmingham, MI U.S.A. Matteo Sabattini

Director IP Policy,

Ericsson, Inc.,

Washington, D.C. U.S.A.

Matteo Sabattini

Director IP Policy,

Ericsson, Inc.,

Washington, D.C. U.S.A. Bowman Heiden

Co-Director, Intellectual Property (CIP),

Visiting Professor, UC-Berkeley,

Berkeley, CA U.S.A.

Bowman Heiden

Co-Director, Intellectual Property (CIP),

Visiting Professor, UC-Berkeley,

Berkeley, CA U.S.A. Richard Vary

Partner,

Bird & Bird,

London, England

Richard Vary

Partner,

Bird & Bird,

London, EnglandTechnology is changing the world today in almost every market and product sector. Consumers are increasingly embracing technologies enabling “people-centric smart spaces.” Smart phones enabled a single device to efficiently navigate the Web and Webbased commerce of purchases and banking, host a multitude of applications, and take and make phone calls, of course. Technology convergence came to the attention of many consumers in the improved functionality of today’s smart phones. Through smart phones, humans can interact with their environment and the IoT. A recent study by Gartner identifies a number of the elements of this people-centric smart space trend that are driving convergence into many products and markets.

Technology convergence in the automotive world is pushing far beyond connectivity enabled by smart phones. In addition to designing and building cars, many auto companies are embracing the opportunity for expanded functionality enabled by technology convergence. Some car companies have stated their intention to become technology companies that provide automotive products and transportation services and a variety of other data-based products and applications.

Clearly some automotive industry leaders understand the change underway with emerging technologies and are positioning to share in the value generated.

Automotive technology associated with vehicle styling, design, interiors, entertainment systems, powertrains and directional control has long been largely the private preserve of vehicle manufacturers and Tier 1 suppliers. New business models have emerged in the automotive space with new players like Uber, DiDi and Lyft offering services that capture the main interface to the traditional vehicle customer, putting increasing pressure on the old business model of personal vehicle ownership.

With the advent of increasing demand for new products and services in vehicles being designed today, vehicle manufacturers and their suppliers are increasingly turning to technical solutions developed outside the traditional automotive world. This demand for new and innovative technologies enabling increasingly connected, self-guided and “greener” vehicles has moved the automotive community to explore, license and integrate technologies developed outside the traditional automotive OEM–supplier ecosystem. This convergence of new, advanced non-automotive technologies into today’s cars has challenged the existing process of IP development and ownership in the automotive world. The need for IP developed outside the automotive ecosystem for these converging technologies has played an increasingly significant role in cooperation and competition in automotive engineering, manufacturing and supply.

These new converging technologies are often developed and owned by players who do not rely on sales to automotive OEMS for the majority of their revenue and profits. Vehicle OEMs and automotive Tier 1 suppliers see the data generated by consumers with their connected vehicle as a new source of profits and revenue growth. What is unclear, for now, is which players will ultimately control and monetize the data generated by these new applications. Providing a path for these converging technologies into cars is no longer optional for vehicle makers. Allowing access to traditionally closed vehicle architectures for new converging technologies has become the “price of entry” for vehicle manufacturers. The first evidence of the trend and the clash between the established automotive order and the new converged playing field came with the automotive connection for telephones, which has become an expectation for most consumers.

The telephone connection to cars accompanied in vehicle consumer services like GM’s On-Star™, Mercedes’s Connected Vehicle Services, BMW’s ConnectedDrive, FordPass™, and Toyota Connected, and became the major bridgehead in the vehicle by players “outside the club” of automakers and suppliers. As 3G cellular technology migrated to 4G/LTE, the situation became more acute when IP and the associated chip and software technology became more widely disbursed, and the phone modem/connection became increasingly integrated into the vehicle electronics architecture (whereby the car takes the communication function and becomes a phone and a car). The value of vehicle connectivity and the related data generated by vehicle owners continues to grow for consumers, vehicle manufacturers and providers of goods and services alike. The connected vehicle not only gives the ability to offer consumers the value of connectivity, it also gives vehicle OEMs significant value through the ability to seamlessly implement over-the-air updates for vehicle systems software, road accident data, and a wealth of information connected to vehicle use patterns and consumer preferences.

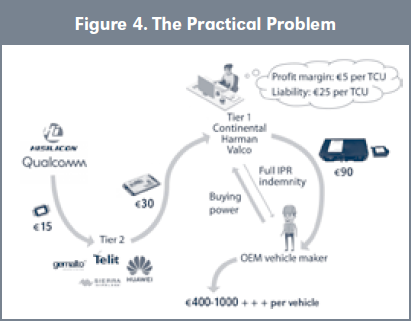

While well-established, efficient industry practices exist for licensing and accessing standard-based communication technologies in the ICT space, industry practices in other verticals are in their infancy and will need time to consolidate and reach transactional efficiencies. Vehicle OEMs have traditionally placed responsibility for securing IP rights and defending OEM customers on matters of infringement squarely on the automotive Tier 1 supply community. Margins in the Tier 1 supply community are generally low in comparison to expectations of key technology IP holders outside the automotive market. Automotive supply contracts are awarded for relatively long periods, in many cases for vehicle program lives of six years or longer. Vehicle program supply contracts awarded to Tier 1 suppliers often include annual price reductions for the life of the program. Annual production volumes are generally large, often with hundreds of thousands to sometimes millions of units and are often awarded to Tier 1 suppliers for delivery in markets around the world.

The existing “comfortable” practice protecting vehicle OEMs from IP infringement through the Tier 1 supply community provides little incentive for OEMs to change the current contract protections. Margins for the telecommunications control unit (TCU), provided by Tier 1 suppliers, have traditionally been so thin that suppliers of the systems to vehicle producers have no ability to cover the value created by IP owners. The value of connectivity to OEMs is high, with studies showing the actual cost of industry rates for the use of cellular standard essential patents (SEPs) being relatively small compared to the economic value generated for car makers.

The answer to the key question for automotive cellular connectivity licenses—that of who pays—remains unclear. It has been estimated that up to 95 percent of the value created by the new V2X connectivity (vehicle to everything) may ultimately accrue to new players in the data-driven automotive applications of the future.

Connected vehicle applications provide insight into IP and licensing issues that will emerge as other, game-changing technologies take their place in vehicles. Self-guided or autonomous vehicle systems are getting welldeserved attention with the promise of eliminating accidents, injuries, and loss of life due to human error. Many of the key developments and IP for self-guided vehicles came from university research and small start-ups, creating many new players in the more static world of automotive supply. The advent of these players created intense interest in acquiring control or developing long-term relations with holders of the IP. Acquisitions and independent R&D efforts by “Mega-Players” outside the traditional automotive supply community are also increasingly changing the basis of competition in the automotive world. A defining characteristic of these new Mega-Players, including Apple, Google, Uber and DiDi, is that most of them have large independent sources of revenue outside the world of automotive supply. These players are increasingly resistant to the standard terms and conditions offered by vehicle OEMS for supply or license of the IP required. Large technology companies have both cash and huge market capitalizations compared to the traditional vehicle producers and aggressively use IP to control the playing field in the market for products and services.

Vehicle electrification is another excellent example of the changing world of automotive technology. The growing market success of electric vehicles is creating new IP power centers in firms like Tesla and Chinese producers like Nio, X Peng, and Li Auto. Traditional vehicle producers like Nissan, GM, VW, BMW and a multitude of others also play a role, but it is interesting to note that the new players have a combined market capitalization of over $600 billion, exceeding the market capitalization of top-10 volume producers of the more traditional global vehicle suppliers. New players are developing IP as they deploy vehicles in global markets with increasing reliance on suppliers of lithium power and battery systems employing lithium. Traditional OEMS are making efforts toward aligning with new energy power sources but are in a brave new world in terms of supply for these essential commodities, with control in the hands of players outside their traditional automotive supply base.

Access to the IP necessary for early adoption of these advanced features and functions remains a key issue for vehicle OEMs. The changing world of developing vehicles for global markets and the massive investment required for self-guided and advanced electric propulsion has resulted in OEM-to-OEM alliances. We believe that the technical roadmap is far from complete in the world market for advanced vehicle systems. The interplay between the vehicles and the smart cities, the IOT, and EV charging network will accelerate market demand for advanced features and software applications. Reliance by vehicle OEMS on the “old IP game” that assigns the supplier base the obligation to manage the cost and licenses for advanced IP is likely not a reliable path to ensure the rights that OEMs require for product leadership. Access to world-class technical and connectivity solutions will rely on vehicle OEMS working with the Tier 1 community and the IP owners to come to a market-based economic solution for IP rights.

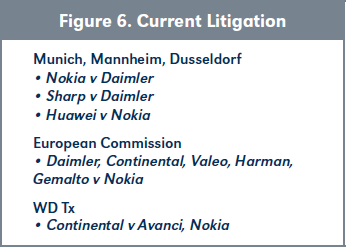

Early indications of the economic value of automotive connectivity are coming from courts evaluating the infringement claims in Mannheim and Munich, Germany. In these cases, decisions that have established the sales value for the mid-level sale of the TCU from the Tier 1 supplier to the vehicle manufacturer do not capture the full economic value of the connection technology to the consumer and to the vehicle OEM, for purposes of evaluating FRAND (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory) license fees.

An example of how the changing market need is impacting vehicle electric and electronic architecture is the Smart Vehicle Architecture, offered by Aptiv in its solution for vehicle signal and power needs. In the Aptiv SVA™ vehicle architecture, many of the more than 100 local-level control units can be “up-integrated” into Power Data Centers and Open Server Platforms (domain controllers) in the vehicle that allow for cost efficiencies and optimized systems packaging in the vehicle. On top of a SVA™ network of domain controllers is the “app store” of vehicle-specific applications selected and managed by the vehicle manufacturer. The selection and availability of these program-layer applications will have strong influence on the key functions consumers see in their vehicles. The program layer, combined with more open software architecture, will enable vehicle OEMs to refresh the applications at various times throughout the program life for major vehicle platforms. The ability to keep new applications coming to the vehicle over the life of any vehicle program will likely become increasingly important for keeping the vehicle competitive over its entire production life.

Various engineering associations facilitate technology introduction into new vehicle systems. Groups such as the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATARC), the German Institute for Standardization (DIN), and many other groups work to provide engineering standards. These standards are established to make new vehicle systems function safely throughout global markets. Patents that are “standards-essential” are often made available at FRAND rates or at no charge by key IP holders. Beyond safety and interoperability matters, significant room remains for market competition through other proprietary IP-enabling advanced system features.

In addition, the converging markets, like telecommunications and IoT, offer solutions in the form of IP consortiums or pools that enable broad access to IP from a variety of owners. Two examples of such patent consortiums providing access to large clusters of IP supporting vehicle connectivity are Avanci and Via Licensing. These consortiums have their origin in the telecommunications IP and IoT worlds, but license IP that helps enable vehicle connectivity. Licenses from Via and Avanci provide efficient access for automotive clients to IP rights (standards essential patents) required for vehicle applications.

The world of automotive production and supply has witnessed enormous change in the 21st Century. The rise of strong emerging vehicle producers and amazing growth in markets like China have driven traditional vehicle producers and their supply base to accept new ways of doing business. Convergence of new technologies from IP owners not dependent on the automotive market changes the power structure and will drive new ways of accessing and managing IP rights. New successful business models have emerged that are challenging the existing order for OEMS and core suppliers involved in automotive design, production, and systems supply. How the value created by these new vehicle systems is apportioned to the various players remains to be resolved in the courts and the markets. Clearly, convergence will continue as long as consumers view their vehicles as a key extension of people-centric smart spaces. The licensing profession has a key role in the process of enabling access to these converging technologies by understanding the forces in play in automotive supply and directing participants toward market-based IP solutions.

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=3897852.