We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

No cookies to display.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

No cookies to display.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

No cookies to display.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

No cookies to display.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

No cookies to display.

Sara Citterio

General Counsel

Trussardi Milano

Milan, Italy

Sara Citterio

General Counsel

Trussardi Milano

Milan, Italy Dario Paschetta

Attorney at law, LL.M.-LSE

FVA LAW

Torino, Italy

Dario Paschetta

Attorney at law, LL.M.-LSE

FVA LAW

Torino, ItalyThe opinions expressed by the authors in this contribution are personal and do not represent the official position of their respective companies.

In the academic landscape and in Italian and international case law, the relationship between Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) and antitrust rules presents a partially contradictory relationship. The former aim to encourage innovation and investment by giving the IPR owner the right to exclude third parties (for a certain period of time) from exploiting a new and original solution to a technical problem that can be realised and applied in the industrial field (the patent), an industrial design (the drawings and models), a distinctive sign (the trademarks) or an original work or database (copyright). The latter, on the other hand, are a set of regulatory provisions whose primary objective is to maximise consumer welfare through a system of rules facilitating companies’ access to the market or, according to the most accredited economic theories, the attainment of economic efficiency through an efficient allocation of resources (so-called allocative efficiency); it is therefore widespread opinion that antitrust law strives to keep markets open. This imperative was in the past equally commonly opposed to the prerogative of IPRs to create reserved market areas.

Such an approach, which was considering these two areas of law to be in radical conflict with each other, may now be considered outdated on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States as in Europe, it is now generally recognised that the so-called dynamic competition brought about by intellectual property rights plays a fundamental role in the protection and enhancement of competition. By incentivising the introduction of innovative products and processes, intellectual property rights contribute to improve consumer welfare by satisfying consumers’ needs more efficiently or by satisfying new needs.

According to this approach, it is now an accepted principle that both disciplines pursue the same goal, i.e., maximising consumer welfare and promoting efficient resource allocation. As acknowledged by the European Commission in the Transfer Technology Guidelines (TTGL) on the application of Article 101 TFEU to technology transfer agreements of 2014, “Innovation is dynamic and essential for an open and competitive market economy. Intangible property rights foster dynamic competition, as they encourage enterprises to invest in the development or improvement of new products and processes; competition acts in a similar way, as it pushes enterprises to innovate. Therefore, intangible property rights and competition are both necessary to foster innovations and to ensure their competitive exploitation.” 2 The same principle can be found in the antitrust guidelines for IPR licensing agreements in the U.S. where it is stated that “The intellectual property laws and the antitrust laws share the common purpose of promoting innovation and enhancing consumer welfare. The intellectual property laws provide incentives for innovation and its dissemination and commerce by establishing enforceable property rights for the creators of new and useful products, more efficient processes, and original works of expression. [...] The antitrust laws promote innovation and consumer welfare by prohibiting certain actions that may harm competition with respect to either existing or new ways of serving consumers.” 3

Although it may be considered unquestionable today that these two disciplines pursue the same objective, this is done from different perspectives and in different ways such that in the practical application of the regulatory provisions, situations may occur in which these two areas of law may enter into conflict. However, this conflict most often appears to be solvable by means of the legislator or by the judges that apply the two sets of rules in a way that both reach the common goal in a coordinated way.

The first step in the antitrust field is the acknowledgement that the notion of anti-competitive agreements or concerted practices between undertakings is a restrictive one. This interpretation clearly emerges from the principle expressed by the Court of Justice in the Groupement des cartes bancaires case, whereby the EU supreme court clarifies the principle that only agreements and practices that by their nature are “detrimental to the proper functioning of normal competition” 4 fall under this prohibition of Article 101 TFEU. Commercial practices involving the exploitation of IPRs are often exempt from the antitrust prohibition since, although they entail restrictions of competition, they generate efficiencies that are sufficient to offset any anti-competitive effects in compliance with the requirements set out in Article 101.3 TFEU, provided that they do not contain hardcore restrictions of competition or excluded restrictions.

In today’s antitrust law, the IPR licensing agreements, while they entail the restrictions of competition which by their nature are necessary for their implementation (e.g., the granting of one or more exclusivities), are in the vast majority considered to have pro-competitive effects because they support the dissemination of technologies, the consequent creation of value, and ultimately help to promote competition by removing obstacles to the development and exploitation of new and/or improved technologies. In particular, in sectors characterised by the existence of numerous patents, “licensing often occurs in order to create design freedom by removing the risk of infringement claims by the licensor” (§17 and §4.1.3 TTGL).

A similar approach is taken in the field of rules prohibiting the abuse of a dominant position. In this case, it is a well-established principle both in the U.S. and Europe that the granting of IPRs does not in itself lead to the creation of a monopoly in the economic sense and, therefore, to market power that makes the IPR holder dominant. Notwithstanding the fact that IPRs constitute legal monopolies, their exercise is very often a source of competitive pressure both on those who do not have these rights—because they are incentivised to create alternative ones—and on the IPR holders—who are incentivised to improve their own IPR-protected products and processes to keep their competitive advantage. What is caught by the prohibition of Article 102 TFEU today is the improper use of the exclusive right, i.e., when it is exercised in a way that entails an exclusion of competitors or an extension of the exclusivity beyond what is legitimately necessary to guarantee the remuneration of the investments made for the creation of innovation and, more generally, the role of the innovation incentive.

The economic and legal fields in which intellectual property rights and modern antitrust law interact are manifold and heterogeneous. For instance, in the field of cooperation among companies, although there is no precise legal definition of agreements pursuing a cooperative objective in pro-competitive terms, it can be said in general that this notion encompasses all agreements primarily aimed to achieve the objectives of rationalising the functioning of the participating companies at the level of research and development, production, procurement, marketing of products or provision of services (e.g., distribution agreements)

and finally at the specific level of technology transfer (e.g., licensing of IPRs).

In line with the aims of LES Italia, the focus of the therein contribution is on the antitrust assessment oftwo specific categories of agreements at the European level: distribution agreements and technology transfer agreements. The former are vertical agreements, i.e., agreements where each contracting party operates at a different level of the production or distribution chain. The latter, on the other hand, may be concluded both between undertakings that are competitors on the market for products and/or services incorporating the technology being transferred and on the technology market, as well as agreements between non-competitors.

One of the objectives of the Treaties of Rome establishing the European Economic Community, which

subsequently permeated all legislation up to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, is the establishment of a common (and then single) European market. The objective of economic integration, based on the free movement of goods, services and productive factors (capital and labour), could not disregard the adoption of a unitary European regulation, which could not be derogated from by national regulations, aimed at eliminating and preventing those barriers potentially capable of altering the economic parity between operators on the European market, which also include anti-competitive conduct by companies.

Article 101 TFEU represents one of the founding bases of the legislation that, within the European Union, is deputed to strictly regulate those practices that must allow economic operators to act in full respect of equal opportunities for development in the market and, therefore, also of competition, while allowing the necessary flexibility to supervisory authorities to assess conduct that could even potentially damage the completion of the single market.

It is based on three fundamental directives: (i) the prohibition (foreseen in the first paragraph) of a series of commercial practices that the European legislator has already identified as being detrimental to trade between Member States by affecting competition between undertakings operating in the single market; (ii) the outright nullity of agreements or decisions prohibited by Article 101 TFEU; and finally, (iii) the exemption of those decisions, conducts and practices of undertakings that are likely to contribute to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress.

Agreements or decisions whose purpose is to make the market behaviour of competitors more pre-visible and, therefore, governable, are void as of right. It is an irremediable nullity, not subject to a statute of limitations, ex tunc, which can be detected ex officio and by anyone who considers himself harmed by an anticompetitive agreement or practice. The distinction that Article 101.1 TFEU makes between restrictions ‘by object’ and ‘by effect’ is substantial: if an agreement has as its object the restriction of competition, it has by its nature such a high potential to produce negative effects on competition that it is not necessary, for the purposes of application5 of Article 101.1 TFEU demonstrate the existence of specific effects on the market, as well as the parties’ intention to restrict competition (although this is an important element of the assessment). There are also agreements whose object is not to restrict competition; however, their anticompetitive effects, even potential ones (as long as they are appreciable), are assessed for the application of Article 101 TFEU.

However, not all agreements between undertakings, especially those between undertakings at a different level of the supply chain, are to be considered as having an anti-competitive object or as having negative impact on competition, since some of them are, on the contrary, capable of developing significant economic potential in EU markets. It is in this light that the third paragraph of Article 101 TFEU must be read, which explicitly admits the possibility that the provisions of the first paragraph may be declared inapplicable to certain agreements, decisions or concerted practices that have as their object the improvement of production or distribution of goods, or the promotion of technical or economic progress, and that—by reserving a fair share of the profits to consumers—do not impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions that are neither indispensable nor constitute a means of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the products. Such agreements (whether individual or categories of them, or concerted practices) which, although restrictive, have the potential to create economic benefits that outweigh the anti-competitive effects, are thus exempted from the prohibitions of Article 101 TFEU, provided they fulfil the four cumulative conditions mentioned above.

The Commission may issue a number of general exemption regulations for certain categories of agreements which, because they do not contain restrictions on the blacklist of severely and objectively anti-competitive restraints and are concluded between undertakings without significant market shares, have the potential to produce positive economic and competitive effects.

Precisely in this respect, agreements between companies operating at different levels of the supply chain(so-called vertical agreements) have been viewed more favourably by the Commission. The latest general exemption6 regulation of vertical agreements (VBER)7 entered into force on 1 June 2022 together with the new Guidelines on Vertical Restraints (VGL),8 and establishes a so-called “safe harbour” for those vertical agreements whose parties do not exceed certain market share thresholds (30 percent) (Article 3), provided that these agreements do not contain hardcore restrictions (Article 4), i.e., all those practices that are considered to be serious restrictions of competition.

The VBER, in addition to redefining the safe harbour, updated the entire antitrust discipline in the light of the exponential development of electronic commerce, which had only been partially regulated by the previous Regulation No. 330/2010.

In particular, in view of the growth of online sales compared to physical sales channels, dual pricing is no longer considered a hardcore restriction (§209 VGL), as it is seen as a legitimate way to incentivise greater investment between on- and offline channels (provided that this differentiation does not have the effect of preventing the actual use of the internet for the sale of goods or services). Similarly, the new GLPs allow that (as part of a selective distribution system) the provider may impose different criteria for on- and offline sales, provided that this solution does not restrict competition.

According to the most recent conclusions of the Court of Justice, in particular the principles set out in the judgments Pierre Fabre9 and Coty Germany,10 only those restrictions on online sales are considered hardcore that effectively prevent, even if indirectly, the use of the internet as a channel for the commercialisation of goods and/or services, as well as those that prevent the use of an entire online advertising channel. Accordingly, limitations tout court of price comparison sites (which are deemed a genuine advertising channel) are prohibited, unless the limitations result from the application of specific and objective quality standards. Similarly, sales using marketplaces may be restricted, as they are deemed to be only one of the online sales methods that may be used by the distributor.

Another novelty of the new VBER is the confirmation of the block exemption of the so-called dual distribution (which occurs when the supplier is also a distributor of its own goods, in competition with its own distributors—Article 2.4), but above all the attention that the European legislator has paid to the critical nature (from an antitrust point of view) of information exchanges at a horizontal level. Abandoning a technical solution based on specific market thresholds, the Commission has specified that in cases of dual distribution between supplier and distributor, exchanges of information are excluded from the benefit of the exemption if they are neither necessary to improve the production or distri

bution of the goods/services covered by the contract, nor directly related to the implementation of the vertical agreement.11

As requested by some stakeholders during the several rounds of public consultations for the review of the 2010 VBER,12 the Commission confirmed its position on “resale price maintenance” (RPM) clauses, which continue to be considered as a hardcore restriction, although with some openings in cases where de facto RPM clauses may be eligible for an individual exemption under Article 101.3 of the Treaty.

RPMs are (Article 4 (a)) agreements requested by an upstream supplier to a downstream buyer (typically a distributor, or a retailer) which, directly or indirectly, have their object of restricting the buyer’s ability to determine its resale prices. This may happen because of contractual provisions specifically preventing the buyer from selling at a price which is below a certain price level determined by the seller.13

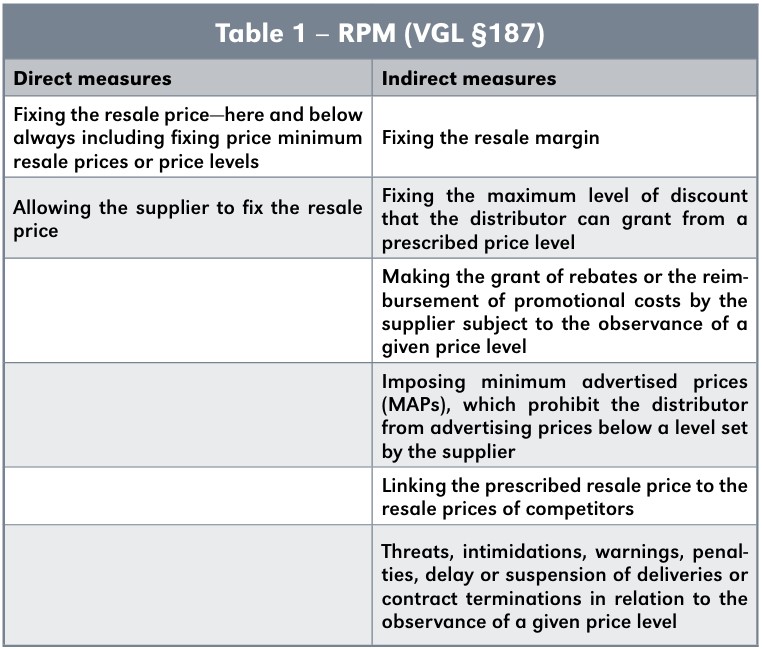

But there may be also contractual provisions that do not directly set the retail price, yet they have the indirect effect of influencing the self-determination of the buyer to freely set its resale price, i.e., by grant ing incentives only to those resellers who conform to a certain price level suggested by the seller, or to a certain resale margin. Several cases of indirect RPM agreements are listed in §187 VGL, but they serve just as an example of any agreement which, although apparently neutral pricewise, in fact influences the ability of the buyer to determine the resale price of any purchased good (see Table 1, in the Figures section).

Contrary to the U.S.,14 RPM is seen negatively by the European antitrust national authorities and the European Court of Justice, as it may both limit (or prevent, as the case may be) the intra-brand competition and facilitate anti-competitive inter-brand agreements between suppliers and/or distributors.

RPM conducts are one of the most sanctioned vertical restrictions by EU Competition State Authorities by far. However, similarly to the 2010 version of VBER,15 the Commission still does not consider a provision containing a maximum resale price, or the recommendation of a resale price, as unlawful per se. It may turn into one if combined with other provisions that have the effect of holding back the buyer from freely fixing the price of the products.

Although the EU Commission takes a strict approach to RPM enforcement, there may be cases when RPM clauses enhance efficiency. Following the suggestions of some national competition authorities during the targeted consultation for the impact assessment of the review of Regulation (EU) No 330/2010, the Commission exemplifies in par. §197 VGL several instances of pro-competitive RPM clauses, mainly related to: i) the launch of new products on the market; ii) short-term promotions (up to six months maximum) and iii) provision of additional pre-sales services by retailers to avoid free riding. Suppliers intending to claim the pro-competitive effect of an RPM clause still have to provide evidence of such effect and prove that all the conditions of Article 101.3 are fulfilled in the individual case. Furthermore, in the new VGL there is another case in which RPM may be exempted, i.e., where “A minimum resale price or MAP can be used to prevent a particular distributor from using the product of a supplier as a loss leader. Where a distributor regularly resells a product below the wholesale price, this can damage the brand image of the product and, over time, reduce overall demand for the product and undermine the supplier’s incentives to invest in quality and brand image. In that case, preventing that distributor from selling below the wholesale price, by imposing on it a targeted minimum resale price or MAP may be considered on balance pro-competitive” (§197 lett. (c)).

The Commission’s position in the new VGL confirms a somewhat more relaxed interpretation in respect to price clauses, despite the different outlook on the subject held by many national authorities and the European Court of Justice, that in several cases considered RPM to be a restriction of competition by object within the meaning of Article 101.1 TFEU. Interestingly though, in one of the most recent cases, the ECJ also16 seems to have softened its approach to RPM conducts, and it decided that hardcore restrictions (the case dealt precisely with an RPM clause) cannot be automatically considered as restriction of competition by object, thus reinforcing the interpretation that the two definitions of hardcore restrictions listed in Article 4 of VBER and the concept of “restriction by object”17 do not overlap.18 The aim of a hardcore restriction, although in principle could raise suspicions given its capability to restrict competition, is only to exclude certain vertical restrictions from the scope of a block exemption. However, a vertical agreement fixing minimum resale prices must also be evaluated in respect to the context of its formation (legal and economic alike) of its content and other consideration (such as “the nature of the goods or services affected, as well as the actual conditions of the functioning and structure of the market or markets in question”)19 to assess whether in fact it constitutes a harm to competition. If it does, given the specifics of the case which must be analysed on a case-by-case basis, then a RPM included in a vertical distribution agreement can be found to be a restriction of competition by object.

The ECJ clarified that the classification of RPM as hardcore restriction does not imply a stigma on its being always a restriction by object. Therefore, national courts cannot just rely on the mere presence of an RPM in a vertical agreement to state that such clause is restrictive of competition beyond any doubt—and beyond any further assessment.

In antitrust law, technology transfer agreements are agreements concluded between two or more undertakings concerning the licensing (or, in some cases, the assignment)20 of IPRs relating to a technology, often covering patent rights, know-how and, in this phase of exponential growth of digital markets, increasingly also software copyrights. Complex contracts combining licences of several IPRs also fall within the same scope.

While licensing agreements are now considered to have multiple pro-competitive effects as mentioned above, there may be particular situations in which such agreements may have anti-competitive effects, e.g., when two competing undertakings use a technology transfer agreement to share a certain market (§169 TTGL) or when the undertakings have a high market share (see below) both in the market for products incorporating the licensed IPR and in the market for licensed technology rights and their substitutes.

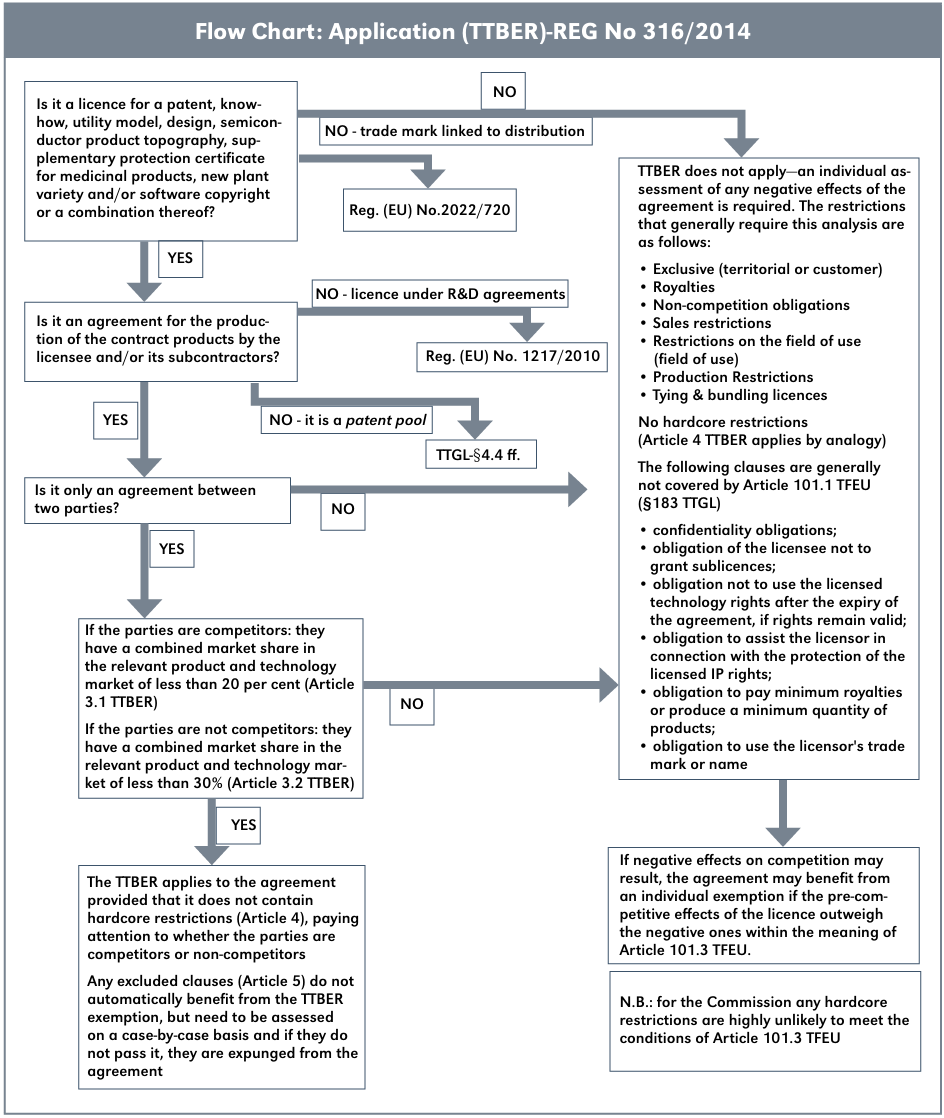

Since in European antitrust law a cartel is not irretrievably prohibited and void if four cumulative conditions, two positive and two negative, provided for in Article 101.3 TFEU are met, the Commission, in order to allow operators to identify which TTAs can be exempted, has also adopted a regulation for this specific category of agreements: Reg. (EU) no. 316/2014 (Transfer Technology Block Exemption Regulation, TTBER)21 accompanied by Guidelines (TTGL) in which the Commission sets out the principles it applies in assessing when TTAs fall within the scope of 101.1 TFEU and in recognising the exemption of the aforementioned regulation.

After setting out the relevant definitions (Article 1) and an article acknowledging the exemption for TTAs containing restrictions of competition falling within the scope of Article 101.1 TFEU (Article 2), the TTBER contains a safe harbour threshold expressed as a percentage of market shares below which it is presumed that the participating undertakings do not have sufficient market power to cause serious risks to competition when they engage in TT agreements (Article 3), then lists a series of hardcore restrictions which, if present in the agreement, irrespective of the market shares of the parties,22 render the exemption in any event inapplicable (Article 4) and, finally, a series of excluded restrictions23 from the benefit of the block exemption (Article 5). For exemption to be granted, agreements must fulfil certain specific requirements.

First, they must be agreements concluded between two undertakings.24 Multilateral agreements, therefore, are subject to individual assessment by analogy with the same principles set out in the TTBER. Similarly, the Regulation also does not apply to agreements establishing patent pools, i.e., agreements whereby two or more undertakings create a technology package that is licensed to pool participants and/or third parties;25 in addition to being multilateral agreements (§56 TTGL), they do not provide for the grant of a particular licence to produce contract products (§247 TTGL). Technology pools, however, have an entire subsection of the TTGL (§4.4).

The TTGLs firstly recognise that pools (and in some cases standards related to them) generate undoubtedly favourable effects for competition and market efficiency: reduction of transaction costs, setting a limit for cumulative royalties (thus avoiding the problem of double marginalisation and the creation of a one-stop shop), and greater efficiency in the management of joint production phases. Afterwards, there can be possible restrictions of the competition that such collaborative instruments between companies may generate, including price fixing cartels, reduction of innovation, foreclosure of alternative technologies, and barriers to entry for new technologies. The main points on which the Commission has focused its regulatory intervention concern the formation (in particular, the selection of the technologies included in the technology pool), establishment and functioning of the pool, as clarified in paragraph 248 et seq.26

Secondly, the TTAs must relate to the IPRs listed in Article 1.1(b), from which list are excluded contracts having as their exclusive object a trade mark or copyright licence which do not relate to software.27 Thirdly, licence agreements must be concluded between undertakings holding a combined share of no more than 20 percent or 30 percent in the two relevant markets indicated above, depending on whether they are more or less in competition with each other.

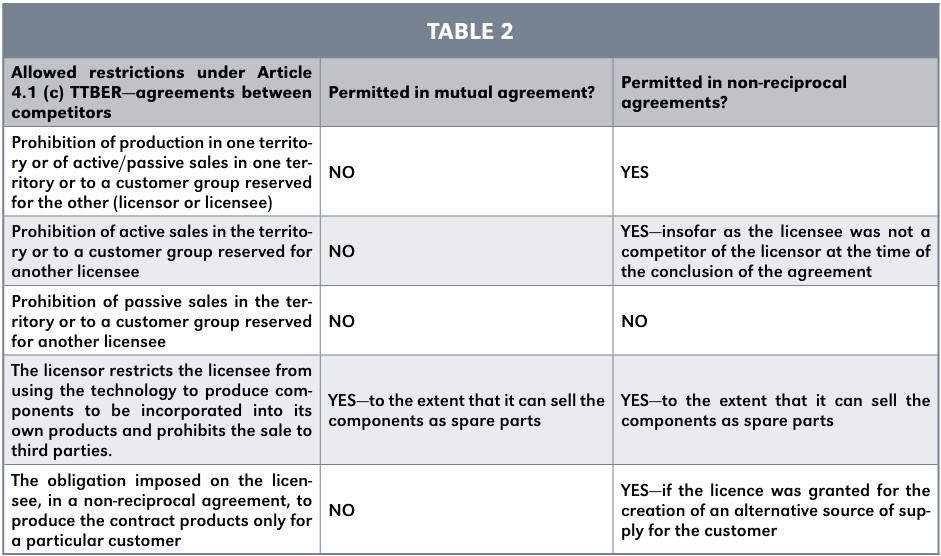

Fourth, Article 4 of the TTBER lists the always prohibited restrictions by making a distinction between the case where the parties are competitors and the case where they are not competitors. In the first case, where anti-competitive effects are more likely to occur, hardcore restrictions are those clauses that: (i) affect the ability of a party to decide on the prices charged for the sale of products incorporating the licensed technology; (ii) concern the limitation of production (with the exception of those imposed in a non-reciprocal agreement);28 (iii) have the sole purpose of sharing markets and/or customers (see Table 2); and (iv) inhibit both parties to the agreement from carrying out research and development (R&D)29 or the licensee from exploiting its technological rights.

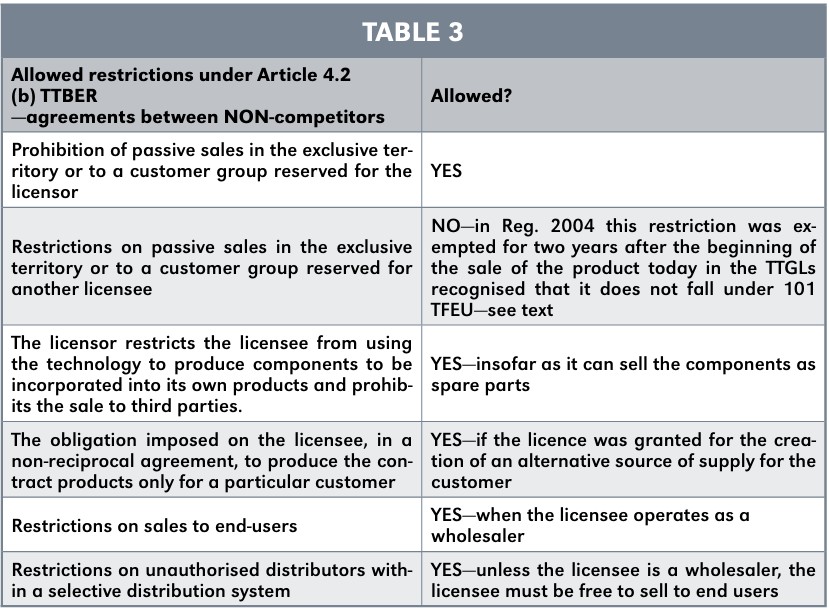

In contrast, when the undertakings concerned are not competitors, the prohibited clauses are less stringent and are:21 (i) the imposition of a minimum resale price (not the mere recommendation or indication of a maximum price as is the case with vertical agreements); (ii) restrictions of the territory (or customers) within which the licensee may make passive sales (except for a number of restrictions which are in practice necessary for the functioning of a licence agreement; see table 3);30 (iii) the prohibition of active and passive sales to end-users imposed on the licensee member of a selective distribution operating at the retail market level.

Whereas in the VGL they represent a hardcore restriction, in the TTA restrictions on passive sales by licensees into an exclusive territory or to a group of customers assigned to another licensee may fall outside the scope of Article 101.1 TFEU, and thus are permissible, if limited to a certain period31 and if they are objectively necessary for the protected licensee to enter a new market by making substantial sunk investments.

Finally, Article 5 lists the restrictions excluded from the TTBER for which a case-by-case assessment is required:32 (i) grant backs (exclusive grant backs) whereby the licensee of a “basic” technology undertakes to assign to the licensor, or to grant under exclusive licence, rights to improvements or new applications developed subsequently, whereas non-exclusive grant back clauses fall under the TTBER exemption;33 (ii) no challenge clauses whereby the licensee undertakes not to challenge the validity of the licensed IPRs;34 (iii) restrictions on R&D when the agreement is entered into between non-competing undertakings.

Exclusive retrocessions require a case-by-case assessment because it is argued that insofar as they prevent licensees from exploiting realised improvements, they deprive the licensee of the incentive to innovate. Some clarifications are needed on this point: (i) exclusive grant back clauses do not always have an overall negative impact on innovation because the licensor, without a contractual mechanism to counterbalance future competition or a strong grant back clause, would not fully license a state-of-the-art technology;35 in such cases, therefore, the benefits that can be achieved in terms of inter-technology competition through the agreement should be weighed as carefully as the possible negative effects in terms of intra-technology competition; (ii) the risk of disincentives to innovation is very low in situations of strong inter-technological competition and multiple competing research poles; (iii) in view of the rationale of the exclusion it can reasonably be argued that the licensor’s co-ownership of improvements is normally not an excluded clause;36 (iv) the payment of a royalty by the licensor makes it less likely that an exclusive grant back obligation leads to a disincentive for the licensee to innovate, even if the legislator does not give any indication as to the extent to which this correspondent must have (§130 TTGL).

In conclusion, both exemption regulations should mark the transition from a legalistic and formalistic European approach to a more economic one. However, on the evidence of the facts, this desirable objective does not seem to be adequately achieved. In the regulation of vertical agreements, in fact, even in the last regulation, apart from a deserving effort to provide more clarification in several crucial areas (such as for instance on the positive effects on competition generated by fixed price policies; §197 VGL), it may be perceived a certain “basic rational of hesitation” in not recognis

ing the positive effects in terms of increased inter-brand competition gathered by certain restrictions on online sales, especially the ones aimed at preserving the value of brands and the substantial investments necessary to face the competition of a digital market. The same can be alleged for TTBER, which needs some important adjustments, especially with a view to favouring those clauses that, while constituting restrictions within the same technology, are nevertheless functional to the development of robust inter-technology competition.

Table 1:

Table 2:

Table 3:

Flow Chart:

1. This article is the English translation with some amendments and updates of a contribution of the same authors published as part of the “Intellectual property: new perspectives for sustainable growth” edited by LES Italy and Netval, 2023 available at https://les-italy.org/pubblicazioni/proprieta-intellettuale-nuove-prospettive-per-una-crescita-sostenibile

2. OJEU L89, 28.3.2014, pp. 3-50, §7.

3. DOJ and FTC, “Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property,” §1, p. 2, available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/guidelines-and-policy-statements-0/2017-update-antitrust-guidelines-licensing-intellectual-property (last accessed 17.3.2023). For an in-depth discussion of the U.S. discipline, see G. COLANGELO, “The Innovation Market: Patents, Standards and Antitrust, in Quaderni di Giur. Comm.,” 397, 2016, pp. 123 et seq. and A. DEVLIN, “Antitrust and Patent law,” OUP, 2016, pp. 407 et seq.

4. European Court of Justice, judgment 11 September 2014, C-67/13, available at www.curia.eu (last accessed 17.3.2023), para. 50.

5. § 21, Communication from the Commission, “Guidelines on the application of Article 101.3 TFEU,” OJEU no. C 101 of 27/04/2004 pp. 97 - 118.

6. As for the motor vehicle sector, the Commission opted for a special regulation whereby the general exemption regulation applies only to agreements related to the distribution of new motor vehicles, while agreements related to aftermarkets are covered by both the general exemption regulation and specific

exemptions set out in Reg. (EU) No 461/2010, which includes a complementary list of prohibited hardcore restrictions (Article 5) justified by certain peculiarities of the aftermarkets and which is accompanied by additional specific guidelines for the sale and repair of motor vehicles and for the distribution of spare parts (OJEU C138, 28.5.2010, p. 16). This regime has been extended until 31 May 2028 by Reg. (EU) 2023/822 (OJEU L 102I, 17.4.2023) amending the 2010 regulation. For a more detailed exam of this specific regime see A. FRIGNANI M. NOTARO, “Il Regolamento 461/2010 di esenzione per categoria degli accordiverticali nel settore automobilistici: la saga dei pezzi di ricambio

non sembra aver ne,” in Dir. Comm. Int., 2010, 4, p. 715 and A. PAPPALARDO, “Il diritto della concorrenza dell’Unione Europea - profili sostanziali, II ed,” UTET, p. 441 et seq.

7. Regulation (EU) No 2022/720, 10.5.2022, OJEU L 134, 11.05.2022.

8. OJEU C 248, 30.6.2022, pp. 1-85.

9. European Court of Justice, judgment of 13 October 2011, “Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmétique,” C-439/09, cited above.

10. European Court of Justice, judgment of 6 December 2017, “Coty Germany,” C-230/16, cited above.

11. See §99 VGL indicating a list of information to which the exemption applies and §100 containing a list to which it does not apply.

12. The public document can be found here https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-11/contributions_summary_draft_revised_VBER_and_VGL.pdf, page 9-10.

13. For a more detailed exam of the new RPM rules in the VBER 2022, see B. ROHRßEN, “VBER 2022: EU Competition law for Vertical Agreements,” Springer 2023.

14. An interesting approach to RPM, which differs from both the U.S. and EU law is the one adopted by Australia. While per se illegal, the Australian Competition law contains processes which can provide legal immunity to practices including RPM. Prior to recent amendments to the Australian Competition &

Consumer Act (ACCA), parties could only seek authorisation for RPM conduct on public benefit grounds. Recent amendments to the ACCA allow parties to also seek RPM immunity through a notification process, which is a significantly simpler process than the authorisation process. For both authorisation and notification processes, the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) will consider whether the public benefits of the RPM conduct outweigh any public detriments. For more details about

the ACCC approach to RPM, see ACCC, “Resale Price Maintenance Notification Guidelines,” 2022, available at https://www.accc.gov.au/about-us/publications/resale-price-maintenance-notification-guidelines (last accessed 06.8.2024).

16. European Court of Justice, judgement C-211/22, “Super Bock Bebidas SA, AN, BQ v Autoridade da Concorrencia,” dated 23 June 2023 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:62022CJ0211 (last accessed 06.8.2024).

17. A “restriction of competition by object” is either a conduct or an anti-competitive practice that is intrinsically damaging competition to the point where no further assessment in regard to their impact or effect on competition is deemed necessary.

18. “(..) as the Commission observed in its written observations before the Court, the concepts of ‘hardcore restrictions’ and of ’restriction by object’ are not conceptually interchangeable and do not necessarily overlap. It is therefore necessary to examine restrictions falling outside that exemption, on a case-by-case basis, with regard to Article 101(1) TFEU.” (ECJ, Judgement C-211/22, “Super Bock Bebidas SA, AN, BQ v Autoridade da Concorrencia,” dated 23 June 2023 § 41).

19. ECJ, judgement C-211/22, “Super Bock Bebidas SA, AN, BQ v Autoridade da Concorrencia,” dated 23 June 2023, § 35.

20. Article 1.1 lett c. (ii) Reg. no. 316/2014.

21. Reg. (EU) No 316/2014, 21.5.2014, OJEU L 93, 28.3.2014, p. 17-23. The current regulation is due to expire on 30 April 2026 and the Commission has started the consultation process ahead of this deadline see https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/13636-EU-competition-rules-on-technology-transfer-agreements-evaluation_en (last accessed 06.8.2024).

22. See Com. Commission “De minimis,” OJEU C 291, 30.8.2014, pp. 1-4, §13.

23. The inclusion in a licence agreement of one of the restrictions set out in the article does not prevent the application of the block exemption to the remainder of the agreement, if that remainder is severable from the excluded restrictions. Only the individual restriction is not covered by the block exemption, which requires an individual assessment (§3.5 TTGL).

24. In antitrust law, in particular European antitrust law, the notion of undertaking is reconstructed in functional terms so that it “encompasses any entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of the legal status of that entity and the way in which it is financed” (See Court of Justice, judgment of 23 April 1991, C-41/90, Höfner and Elser v. Macrotron, §21). For a more detailed discussion of the concept of undertaking see A. FRIGNANI S. BARIATTI, “EU Competition Law, in Trattato di dir. Comm. and Dir. Pub. Econ.” (edited by F. GALGANO), Vol. LXIV, 2016, Cedam, pp. 83 et seq.

25. As recognised by the Commission itself, technology pools can be either simple arrangements between a limited number of parties or complex organisational arrangements whereby the organisation of the licensing of the pooled technologies is entrusted to an independent body. In both cases, the pool may allow licensees to operate on the market on the basis of a single licence. For an in-depth discussion of the European regulation of patent pools, see A. FRIGNANI, “Patent pools after EU Reg. no. 316/2014 providing for a block exemption of categories of technology transfer agreements,” in Dir. Comm. Int., 2016, no. 2, p. 343.

26.The Commission draws two basic distinctions, between: a) complementary technologies, both of which are necessary for the production of the product, and substitute technologies, which individually allow the holder to produce the product; b) essential and non-essential technologies, depending on whether or not there areno substitutes, inside or outside the pool, for the production of the product or are an essential element to meet the standard followed by the pool (technologies essential to the standard). While pools of complementarytechnologies generally have positive effects for competition, the massive inclusion of substitute technologies in pools makes an exemption unlikely.

27.A trademark licence agreement will only be assessed under the TTBER if it relates to goods or services obtained from technologies covered by agreements falling within Regulation No 316/2014. When, on the other hand, such agreements are part of a distribution agreement (e.g., a commercial affiliation such as a franchise agreement) or selective distribution agreement, they will be assessed in light of the provisions set out in VBER.

28.For the definition of reciprocal and non-reciprocal TTAs, see Article 1.1(d) and (e) TTBER.

29. This is except where such a restriction is ‘indispensable to prevent disclosure of the licensed know-how to third parties.’

30. Unlike in the case of vertical agreements, in the case of licence agreements not only restrictions on active (i.e., solicited) sales are permissible, but also certain restrictions on passive (i.e., unsolicited) sales.

31. The TTGLs indicate that in most cases two years are sufficient to recover the investment, but also recognise that in certain cases, the licensee may need a longer protection period to recover the costs incurred (§ 126).

32. In the consultation process concerning the evaluation of TTBER 2014 LES Italy expressed the view that in the new TTBER “should be clarified that being the co-owner of the improvements is not an exclusive grant-back. Often when two companies cooperate and the IP under license (i.e., trade secrets protecting data) is used to create further technical results which are eligible for IP protection in many cases the licensor and licensee agree to be co-owners of the IP rights insisting on such improvements. LES Italy also suggests to clarifying what consideration for exclusive grant back is able of offsetting pro-competitive effects as stated in the current §130 of TTGL or, in case, to provide more guidance in order to allow companies to assess what is the level of consideration that is the relevant factor in the context of its individual assessment under Article 101.” For more detail please see the full contribution at the following link https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/13636-EU-competition-rules-on-technology-transfer-agreements-evaluation/public-consultation_en (last accessed 06.8.2024).

33. In the 2004 Rules it was different: exclusive grant back obligations on non-separable improvements were exempted in the same way as non-exclusive grant back clauses. Exclusive grant back obligations on severable improvements, on the other hand, were already excluded from the exemption. See J. MARKVART, “The Treatment of Exclusive Grant Backs in EU Competition Law,” in Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 2018, Vol. 9, No. 6, p. 361. It is important to point out that the grant back obligation is essential for the operation of a patent pool as it precludes holders of fundamental rights from benefiting from the single licence offered by the pool’s administrator and at the same time from engaging in hold-up practices to the detriment of the other pool members. Without an obligation of retrocession on the part of all breeders, the patent pooling agreement would hardly be concluded. On this point see O. BORGOGNO, “Il contratto di patent pooling: tra antitrust e proprietà intellettuale,” 2015, pp. 191 available at the following link https://www.studiotorta.com/tesi-contest/ (last accessed 6.8.2024).

34. This is not an absolute prohibition. Article 5.1(b) itself states that it is “without prejudice to the possibility, in the case of an exclusive licence, to terminate the technology transfer agreement if the licensee contests the validity of any of the licensed technology rights.” For a more detailed discussion of the scope of the exclusion see §133 et seq.

35. In this case, the licensor would at most license a ‘slightly obsolete’ technology. The licensor would then have to spend resources to develop technologies that bridge the gap between the licensor’s cutting-edge technology and the licensed technology before being able to develop new technologies. In this scenario, therefore, an exclusive grant back clause can contribute to the dissemination of innovative knowledge and accelerate the overall innovation process of the system, especially in cutting-edge technology sectors.

36. Provided that the by-laws governing the community do not provide for mechanisms that effectively exclude the exploitation of the improvements also by the licensee.