We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

No cookies to display.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

No cookies to display.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

No cookies to display.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

No cookies to display.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

No cookies to display.

Ashley J. Stevens, D.Phil, CLP, RTTP

President

Focus IP Group, LLC

Winchester, Massachusetts, USA

Ashley J. Stevens, D.Phil, CLP, RTTP

President

Focus IP Group, LLC

Winchester, Massachusetts, USA John A. Fraser MA, CLP, RTTP

President

Burnside Development& Assoc. LLC

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

John A. Fraser MA, CLP, RTTP

President

Burnside Development& Assoc. LLC

Bethesda, Maryland, USA Alexandre Navarre, PhD, MBA

Vice President

Numinor Conseil Inc.

Pointe Claire, Quebec, Canada

Alexandre Navarre, PhD, MBA

Vice President

Numinor Conseil Inc.

Pointe Claire, Quebec, CanadaThe cognitive psychologist Barbara Drescher famously said: “The plural of anecdote is data.” In this article we step back from the individual cases described in the preceding articles to ask and attempt to answer questions about the history, business and funding models, strengths and challenges of multi-institutional tech transfer offices (MiTTOs). We try to draw broad conclusions, quantitatively wherever possible, supported by the experiences of the various MiTTOs described in the preceding articles. This article addresses the following issues:

We thank our outstanding group of collaborating authors of the different articles in this special issue, whose observations and accounts provided the input to this analysis: José Manuel Pérez Arce, Carlos Báez, Jaci Barnett, Catalina Bay-Schmith Cortés, Tim Boyle, Brett Cusker, Anne-Christine Fiksdal, John Grace, David Gulley, David Henderson, Tom Hockaday, Kosuke Kato, Ignacio Merino, Lasse Olsen, Jorun Pedersen, Henric Rhedin, Santiago Romo, Anil Sadarangani, Andy Sierakowski, Adrian Sigrist, Christian Stein, Koichi Sumikura, Randi Elisabeth Taxt, M. Carme Verdaguer, Vijay Vijayaraghavan and Bram Wijlands.

As discussed in the introductory background article, we identified three approaches to creating MiTTOs:

NMiTTOs are the most recent organizational structure. The structure was adopted to provide a local implementation of a national system rather than the single, centralized approach of an NTTO. From an organizational perspective, we identified 35 MiTTO organizations:

They are shown in Table 1.

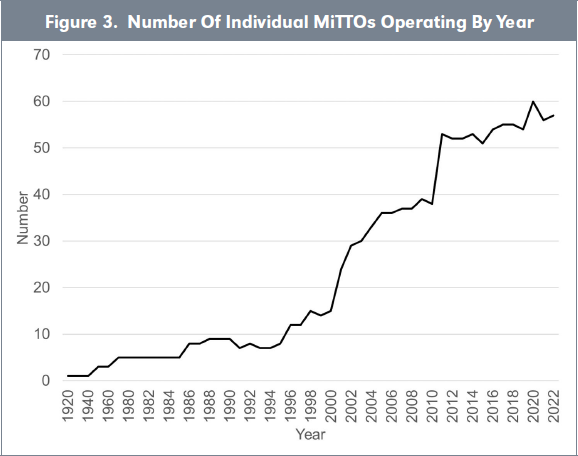

However, the number of individual MiTTOs operating is much larger than the number of umbrella organizations because the five NMiTTOs are networks of RTTOs covering entire countries.

There were originally 18 MiTTOs in the German PVA network, 14 Sociétés d’Accélération du Transfert de Technologies (SATTs) in France while the Department of Biotechnology network in India comprises seven RTTOs, the Norwegian Network currently has eight MiTTOs and the Chilean Hub network includes three organizations. Furthermore, the Quebec SVU program comprised four individual SVUs. In total, therefore, we have identified 83 MiTTOs that have been or are still in operation.

Clearly, MiTTOs have played, and are continuing to play, a major, indeed pivotal, role in the development of tech transfer around the world. We do not believe the importance and scale of this class of organization has been identified before this special issue.

Table 2 shows the number of MiTTOs in each country. Sixteen countries have had at least one MiTTO. The U.S. has implemented the greatest number, eight, of which three were attempts to do tech transfer on a for-profit basis and make a return on investment that were ultimately unsuccessful.

Canada has had four MiTTOs, nine countries have had two and five have had one.

In Table 1 we also summarize the operating history of the 35 MiTTO organizations. The columns are as follows:

If there is no year shown in either the “End Tech Transfer” or “End” columns, the MiTTO is still operating. In that case, the duration is calculated from the start date to 2022.

Sixteen of the MiTTOs are currently still operating as TTOs:

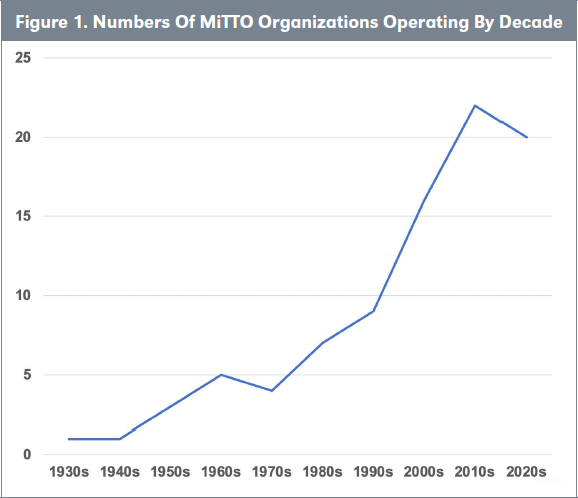

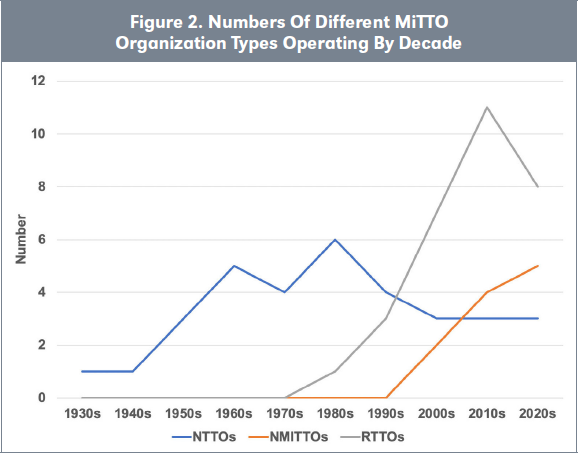

In Figure 1 we show the total number of MiTTO organizations operating by decade, and in Figure 2 we show the number of each of the three types of MiTTO organizations operating by decade. In Figure 3 we show the number of individual MiTTOs in operation by year.

Several observations are apparent from these charts:

Table 3 summarizes the number of years each type of MiTTO organization was in operation.

NTTOs show the longest duration, with an average life of 26 years, dominated by those in Canada, the U.K., and the U.S. Indeed, RCT in the U.S., successor in interest to Research Corporation, the first TTO ever to be established, is still in operation after 110 years, though its duration as an NTTO was “only” 72 years.

As discussed above, NMiTTOs are the newest implementation of MiTTOs. There are five networks, and all five are still in operation. While the members of the DBT Network in India and the HubTec Network in Chile all came into operation roughly simultaneously, the same is not true for the members of the German, Norwegian and French networks, where MiTTOs were created over a period of years and joined the network.

In both Germany and Norway, the first MiTTOs were established in 1986 and 1990, respectively, before the law was changed to require institutional ownership of academic IP. There was a substantial increase in the establishment of MiTTOs within a year or two of the law change followed by a trickle of additional establishments until quite recently. All of the Norwegian MiTTOs are still operating; three of the German PVAs ceased operation between 2015 and 2021.

RTTOs have the same duration as the NMiTTOs, with an average of 11 years, three of which have been operating for around 20 years—the network of four Sociétés de Valorisation in Québec, Canada and Tohoku Techno Arch and Techno Network Shikoku Co., Ltd. in Japan.

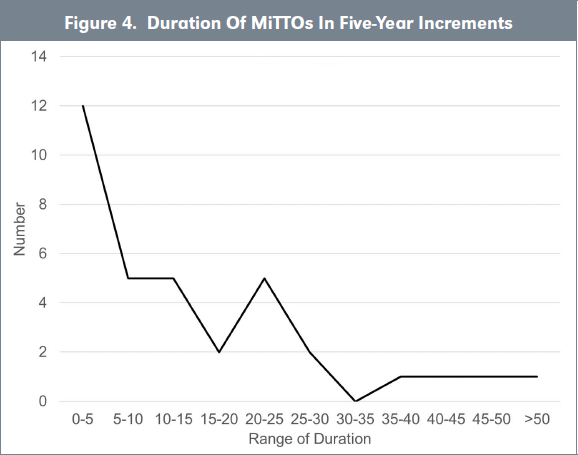

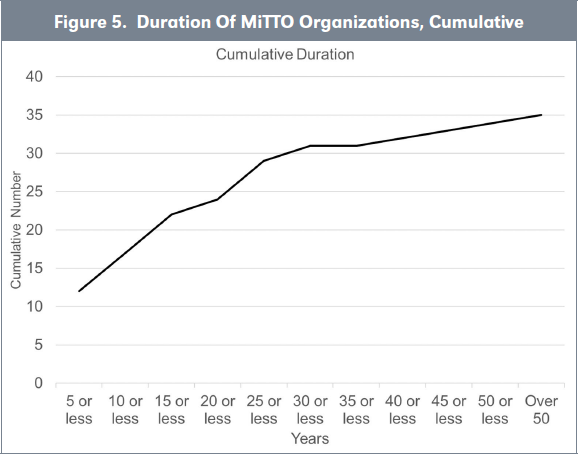

In Figure 3 and Figure 4 we plot the duration of the MiTTOs in years, respectively, in five-year increments of duration, and cumulatively.

The largest cohort, 12 or 36 percent of all MiTTO organizations, operated for five years or less, and over half of all MiTTO organizations operated for 10 years or fewer. At the other end of the duration distribution, 11 MiTTO organizations, a third of the total, have operated for 25 years or more, and 16 are currently operating.

The distribution is essentially bimodal. A large number had a short duration, while others lasted a very long time, and around a third of the cohort are still operating. This data is consistent with the accounts in the preceding articles, which make it clear that some MiTTOs served a catalytic role in kickstarting tech transfer in a particular ecosystem and were then replaced by individual institutional TTOs. Whether that limited lifetime and role was the original plan is beyond the scope of this analysis.

It is noteworthy that in Chile, tech transfer started with an NTTO, OTRI, that CORFO, the agency that funded OTRI, ended support in favor of each institution having its own TTO, but after five years realized that the demographics, geography and scale of academia in Chile made this plan unrealistic and has returned to supporting an NMiTTO of three Hubs covering the country.

Additionally, these data need to be put in the context that tech transfer only existed as an organized activity in seven countries prior to around 1990—Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Norway, Spain, the U.K. and the U.S.—so that in the rest of the world, tech transfer has only existed for 20 years or so.

Of the 16 MiTTOs currently in operation, 14 appear to represent a stable, long-term solution to their members’ tech transfer needs and appear to have an assured source of funding, either internal or external. It is not clear whether the remaining two, the DBT Network in India and the Hub network in Chile, will be funded for the long term. Both are approaching the end of their initial round of funding and the funding agencies are discussing extending the period of funding.

The vast majority of the MiTTOs reviewed in this project were newly established organizations created to carry out tech transfer activity for their member institutions.

However, five were pre-existing organizations that transitioned into MiTTOs:

All of the MiTTOs reviewed used one or a combination of the following funding models:

Next, we examine these models and their implications.

a. External Funding

In this model, the MiTTO carries out all the tech transfer functions for the member institutions using funding provided by a third party, generally with all the revenues generated flowing back to the inventing institutions.

The funding provider is most often the central government, though TULCO in North Carolina in the United States was funded by the Triangle Universities Center for Advanced Studies Inc., whose mission was to support the three universities in the Research Triangle, and the Washington Research Foundation in the state of Washington was funded by a line of credit guaranteed by 35 companies in Seattle. The National Research Development Corporation in the U.K. was an independent public corporation, not a government department, and did not receive annual grants but was financed from government loans under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Technology and was required to balance its books in the long term. The corporation’s borrowing powers were initially set at £10 million, which was increased to £25 million in 1965. PRSTRT in Puerto Rico is funded by excise taxes on Puerto Rican rum sold in the U.S. and a pharma /medical device manufacturers tax and funds its TTO out of these revenue streams.

Obviously, an external funding model is extremely attractive to the member institutions, who get all of the benefits of a tech transfer capability without having to bear any of the costs. Equally obviously, the main issue with such a model is sustainability. If the external provider of funds decides to stop providing the funding, the MiTTO will either cease to operate, must find a new funder, or must transition to the second and/or third models.

b. Member Funding

In this model, the member institutions agree to provide the funding for the MiTTO’s operations and receive all of the income generated from their inventions.

Institutions generally commit to this model to achieve economies of scale and to be able to share access to specialized skills that no one institution could afford individually.

Several of the MiTTOs that seem to have been most successful (as measured by their duration and on-going operations)—Unitectra and Ascenion—fall in this category.

In four other cases, rather than a new MiTTO being created, a larger institution with an established TTO secured funding to expand its activities to provide tech transfer services to a number of smaller institutions.

— Research Corporation used the income from the electrostatic precipitator and the vitamin B1 patents to offer tech transfer services to other institutions and received a revenue share from new commercialized technologies.

— In South Africa, Nelson Mandela University secured external funding to allow it to establish the Eastern Cape RTTO and serve three additional, smaller institutions.

— Technology and Innovation Management used internal funding to turn West Australian Product Innovation Centre into an RTTO serving Western Australia.

— UniQuest, also in Australia, was a hybrid of two models, with the eight partner organizations providing some of the funding for UniQuest’s activities on their behalf and with UniQuest also receiving a share of revenues from deals.

c. Revenue sharing

In this model, an independent MiTTO provides tech transfer services for the member institutions and keeps a share of the revenue generated to fund future activities.

Tech transfer inevitably takes time to generate revenues, as licensees need to be found, agreements negotiated and products developed, tested and sold by the licensee based on the technology licensed. Studies in the U.S. by the University of California system and Columbia University have shown that technologies take a median of four years just to be licensed. This means that half of the licenses take MORE than four years to be signed, and additional time will be needed for product development, testing and market introduction until royalties are received. Therefore, MiTTOs operating on this model will likely need start-up funding to sustain their operations until income starts to be generated that they will share in, but, hopefully, they will achieve sustainability in the longer term.

Another issue with revenue sharing as a route to sustainability is that it can result in the MiTTO being under pressure to be highly selective in the technologies that are accepted for commercialization. This in turn results in those faculty members whose technologies are not selected feeling disenfranchised and excluded, weakening support for the MiTTO. Additionally, with the benefit of hindsight, the member institutions may resent the share of income retained by the MiTTO.

In Table 4 we show the funding sources used by the MiTTOs we identified. External funding was the source used by over half of the MiTTOs, followed by a share of royalty income. Only five MiTTOs have been internally funded—Ascenion in Germany, Technology and Innovation Management in Australia, Tohoku Techno Arch and Techno Network Shikoku Co., Ltd. in Japan, and Unitectra in Switzerland. As we have noted, this appears to be a successful, stable, long-term model. UniQuest was funded internally but also included a revenue share, as did the SVUs in Quebec and the SATTs in France.

A royalty sharing model was the dominant model in the U.S., being used by five of the eight MiTTOs, including the three attempts at a for-profit model. The remaining two—TULCO and the federally funded Tech Link, which supports federal laboratories—used external funding.

The most common reason for establishing a MiTTO is to kick-start commercialization in the member institutions. By making the MiTTO’s services available to the member institutions at no cost, acceptance of tech transfer is generally greatly accelerated.

MiTTOs, particularly NTTOs and NMiTTOs, provide a convenient pathway for government to support tech transfer in an entire ecosystem, either initially to kick-start it, or as an ongoing provider of support.

Obviously, most MiTTOs are created with a commercial orientation and culture, not an academic one. They can immediately introduce this commercial orientation and culture to their member academic institutions, whose internal, traditional academic culture would adapt to commercialization more slowly.

One of the major benefits of a MiTTO is that it provides skills the member institutions could not justify individually and can immediately provide access to a critical mass of personnel, resources and, hopefully, experience.

Another benefit is that a MiTTO has the potential to create more viable start-ups and licenses by aggregating complementary technologies it sees coming from different member institutions.

Finally, an NTTO and even an RTTO will provide an early vehicle to communicate with government about the importance of tech transfer to the government and to lobby for support. Later in the evolution of the ecosystem, this role will generally transfer to a tech transfer association that will have been created as more institutions create their own individual TTOs.

These benefits are summarized in Table 5.

Many of the MiTTOs discussed in the articles in this special issue were established at the inception of tech transfer in their particular ecosystem.

In Canada, France, the U.K. and the U.S., tech transfer got started with NTTOs doing the tech transfer for the whole country. In the U.S., Research Corporation resulted from private sector activity, while CPDL in Canada and NRDC in the U.K. were the result of government initiatives, as were first ANVAR in France and more recently the SATTs. In each country, the NTTO was the primary vehicle for tech transfer for 40-50 years until the 1980s, when legislative changes led to their roles being replaced by TTOs established by individual research institutions. RTTOs in the states of North Carolina (TULCO) and Washington (WRF) were established to jump-start tech transfer in those states and have since been supplanted by individual institutional TTOs.

The German and Norwegian NMiTTO networks were largely established after the ownership paradigm for academic IP was changed to ensure that the benefits of the change were realized. The DBT network in India was established in 2020 and was clearly motivated by a desire to jumpstart tech transfer in India. The Quebec SVUs and the French SATTs have had a similar motivation.

Tech transfer is a challenging undertaking in the best of circumstances, involving attempting to commercialize early stage, unproven technologies of unknown market potential created by independent, strong-willed faculty members, with inadequate human and financial resources.

Assigning responsibility for this activity to an unaffiliated, external organization only adds to these challenges.

In Table 6 we categorize the challenges identified by the various MiTTOs into four categories:

Not all of these challenges are encountered by each MiTTO, but the table perhaps explains why 19 of the 35 MiTTOs we identify are either no longer carrying out tech transfer or are no longer in existence at all. The accounts of individual MiTTOs in the articles in this special issue frequently identify the MiTTO as experiencing one or more of the issues listed below.

Some of these challenges are:

Most externally funded MiTTOs have been funded for a defined period. The World Bank appears to have provided the shortest duration of funding, for three years to the Indian DBT project, though there has been a one-year, no-cost extension because of pandemic delays and a further extension of funding is being discussed. Biotectra was funded by the Swiss government for three years and was superseded by individual institutional TTOs and one RTTO, Unitectra. In Chile, CORFO initially funded OTRI for three years starting in 2005, with subsequent extensions until 2011. It has subsequently funded the three HubTech MiTTOs for five years starting in 2016, which was the initial funding term for TULCO in North Carolina in the late 1980s. Five years appears to be as long an initial duration as most governments will be prepared to fund an activity, though the French government initially committed to fund the SATTs for 10 years, as did the Quebec Government. Frequently, government has an unrealistic expectation that the MiTTO can be self-sustaining after five or even 10 years of support.

That said, it currently appears that the French government is prepared to partially fund the SATTs on an on-going basis as well as the Quebec Government with Axelrys, the successor to the four SVUs. In Canada, other provincial governments have had programs or grants supporting TTOs as well as the maturation and early-stage development of technologies. Those have recognized the high-risk nature of such activities and stepped-up to compensate for the reluctance of universities to invest in what is deemed commercial activities.

The longest duration of direct government support documented in this special issue is in Norway, where the Norwegian Government has funded the official Norwegian TTOs through the Norwegian Research Council continuously since 1995, although the rules and framework conditions for this funding have changed periodically and are now again in flux after 2023.

The desire to avoid depending on potentially fickle external sources of funds is the motivation for revenue sharing business models, but these come with their own challenges. For revenue sharing models to be successful, they need a critical mass of commercially successful technologies to generate an adequate cashflow to support ongoing operations, and will generally need a grant to fund their initial activities until significant income starts to be received. As an example, Washington Research Foundation’s initial activities were funded by a $1 million line of credit guaranteed by 35 companies in Seattle.

MiTTOs appear to have on-going viability in smaller ecosystems, such as the Hub network in Chile, or when serving smaller institutions in larger ecosystems, such as the Japanese and Swedish RTTOs that serve smaller institutions in the same region. Bulgaria, with a population of only seven million, is currently establishing an NTTO.

The collective experiences and demise of the three organizations reviewed in this special issue that were set up as for-profit entities—University Patents, University Technology Corporation and University Science, Engineering and Technology—seem to conclusively answer the question of whether tech transfer can be a for-profit activity in the negative. University Patents lasted close to 50 years until it finally faded into the sunset, but the other two each lasted less than five years.

On the other hand, two not-for-profits which followed a revenue share business model—Research Corporation Technologies and Washington Research Foundation—were highly successful financially, generating respectively billions and hundreds of millions of dollars in income, and are still operating, albeit not as MiTTOs but as venture funds, investing the surpluses their tech transfer activities generated back into the innovation ecosystem.

What explains the difference between the for-profit failures and the not-for-profit successes?

The answer is probably a combination of luck and critical mass. University Patents started out with a few highly profitable technologies, but had an inadequate technology flow from the relatively small number of universities that it served and failed to replace the profitable initial technologies with equally profitable new technologies when the original patents expired. It eventually started to cut back and be more and more selective in the technologies it took on, starting a downward spiral.

Research Corporation Technologies, as successor to Research Corporation, was in a unique place and had enjoyed essentially monopoly access to U.S. academic technologies for decades. It was good at picking winners, so it systematically replaced its expiring revenue generators with new sources of income. WRF on the other hand was just plain lucky. It came into being just as the genetic engineering revolution was in full swing and quickly came up with a few highly profitable technologies. The history of the issuance of the Hall yeast patents also worked in its favor, as more products were in the market when the patents finally issued.

A 2009 study,2 based on a survey carried out in 2006, showed that 52 percent of U.S. TTOs had operating expenses (personnel, patent and all other costs) that exceeded the gross income they received, and only 16 percent of TTOs retained enough of the income they received after distributions to inventors and for research to cover their operating expenses. Periodic modeling of sustainability carried out using AUTM Annual Survey data, which collects data on patent expenses and reimbursements, staffing levels and income, combined with AUTM Salary Survey data, show that these 2006 results are still broadly applicable today. Tech transfer is quite simply not a predictably and reliably profitable business. The reasons are well known to all practitioners:

There are occasional home runs, but they occur in unpredictable places—City of Hope Hospital, Northwestern, UCLA, Emory, New York University, Florida State University, etc. The strategic plan for all TTOs— both MiTTOs and individual institutional TTOs—must be simply to take as many shots on goal and to get on base (to mix sporting metaphors!) as often as possible, by licensing as many technologies as possible, and not treating every invention as a home run and trying to squeeze the last nickel out of it.

MiTTOs that attempted to fund their on-going activities through retaining a share of revenues—Research Corporation, University Patents, University Technology Corporation, WRF, etc.—retained 40 to 50 percent of the revenues. UTC retained the most, 58 percent—16 percent to cover patent expenses and 42 percent to fund UTC’s operating expenses and profit—leaving only 42 percent to the university.

This level of revenue diversion seems to have been a driver for institutions to believe they could do the work themselves at a substantially lower cost. This, together with the desire to have more control over their tech transfer activities, appears to have been the driver for most institutions in developed economies to stop using an MiTTO and set up an internal tech transfer capability, which is certainly the norm in most major ecosystems today.

Experience seems to have validated this expectation. There are two broadly followed income distribution models used in institutions today:

Another interesting analysis is whether the MiTTO just does tech transfer for its member institutions or whether it is also involved in other stages of the innovation ecosystem. In some cases, the MiTTO does more than just tech transfer:

Several of the MiTTOs whose tech transfer business slowly disappeared as their member institutions took over responsibility for their own tech transfer utilized their share of the revenue stream from their past deals to create early-stage venture funds, several of which continue today, long after the MiTTO’s tech transfer activities have gone away:

This review has identified the important role that MiTTOs have played and are continuing to play in the development of tech transfer globally. Some key conclusions are:

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=4255250.

Ashley Stevens is President of Focus IP Group, a consulting company providing consulting, educational and legal services in IP, technology commercialization, tech transfer and valuation. Previously, he was Executive Director of Boston University’s Office of Technology Transfer for 17 years, following four years in a similar role at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. He teaches and publishes extensively on various issues affecting the tech transfer ecosystem and is a Past President of AUTM.

John A. Fraseris President of Burnside Development & Assoc., LLC, a company providing consulting, educational and legal services globally in IP, technology commercialization and financing, technology transfer and knowledge exchange. Previously, he was Assistant Vice President of Florida State University’s Office of Technology Commercialization for 18 years, as part of his career of heading four academic TTOs— two in Canada and two in the United States. He cofounded three start-up companies and was the VP of a private venture capital firm after a decade as a senior officer of the Canadian counterpart of the National Science Foundation. He holds a master’s degree in biochemistry from the University of California Berkeley. He is also a Past President of AUTM.

Alexandre Navarrehas had a career dedicated to innovation in industry with Dow Chemicals, with the Canadian Federal Government, and with university tech transfer offices as director (McGill and Western Ontario) and as founder and CEO of one of the French SATTs. He was also Quebec manager of the Canadian Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), a founding member of ACCT Canada and a long time chair of the Development Committee of the Canadian AUTM section. Actively retired, he currently consults on innovation and IP policy issues and writes articles on innovation challenges.

Table 1. Key Dates Of MiTTO Operations |

|||||

| Precursor | Start | End of TT | End | Duration | |

| Single NTTOs | |||||

| Research Corporation / RCT, US | 1912 | 1937 | 2009 | 72 | |

| Canadian Patents and Development Limited (CPDL) | 1947 | 1990 | 43 | ||

| National Research Development Corporation / BTG, UK | 1949 | 1985 | 2020 | 36 | |

| University Patents, Inc., US | 1964 | 2010 | 46 | ||

| ANVAR, France | 1967 | 1979 | 2005 | 26 | |

| University Technology Corporation, US | 1986 | 1989 | 3 | ||

| University Science, Engineering and Technology, Inc., US | 1986 | 1990 | 4 | ||

| Biotectra, Switzerland | 1996 | 1999 | 3 | ||

| Tech Link, US | 1996 | 26 | |||

| Oficina de Transferencia de Resultados de Investigación, Chile | 2005 | 2011 | 6 | ||

| Ascenion GmbH, Germany | 2001 | 21 | |||

| UNIVALUE, Spain | 2011 | 2015 | 4 | ||

| National Center for Technology Transfer, Bulgaria | 2022 | 0 | |||

| Network of MiTTOs | |||||

| PVAs, Germany | 2001 | 21 | |||

| Norwegian Network | 2004 | 18 | |||

| Sociétés d’Accélération du Transfert de Technologies, France | 2011 | 11 | |||

| Chilean Technology Transfer Hubs | 2016 | 6 | |||

| DBT Network, India | 2020 | 2 | |||

| RTTOs | |||||

| Washington Research Foundation, US | 1981 | 1992 | 11 | ||

| Triangle Universities Licensing Consortium, US | 1988 | 1995 | 7 | ||

| Unitectra, Switzerland | 1999 | 23 | |||

| Technology and Innovation Management Pty Ltd, Australia | 1984 | 1990 | 1998 | 2013 | 8 |

| Tohoku Techno Arch, Japan | 1998 | 24 | |||

| Sociétés de Valorisation, Québec, Canada | 2001 | 2020 | 19 | ||

| Techno Network Shikoku Co., Ltd. , Japan | 2001 | 21 | |||

| Consorci de Transferencia de Coneixement, Spain | 2004 | 2010 | 5 | ||

| C4 Ontario, Canada | 2005 | 2010 | 5 | ||

| UniQuest, Australia | 1996 | 2005 | 2013 | 8 | |

| Innovation Office West, Sweden | 2009 | 13 | |||

| Innovation Office Fyrklövern, Sweden | 2009 | 13 | |||

| Serbian Innovation Fund | 2011 | 11 | |||

| Eastern Cape RTTO, South Africa | 2007 | 2011 | 2014 | 3 | |

| KwaZulu-Natal RTTO, South Africa | 2014 | 2019 | 5 | ||

| Puerto Rico Science, Technology and Research Trust TTO | 2004 | 2017 | 5 | ||

| Axelrys, Canada | 2020 | 2 | |||

Table 2. Number Of MiTTOs By Country |

|

| Country | No. of MiTTOs |

| US | 8 |

| Canada | 4 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Chile | 2 |

| France | 2 |

| Germany | 2 |

| Japan | 2 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Spain | 2 |

| Sweden | 2 |

| Switzerland | 2 |

| Bulgaria | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| Serbia | 1 |

| UK | 1 |

Table 3. Number Of Years MiTTO Organizations Were In Operation |

|||

| NTTO | RTTO | NMiTTO | |

| Number | 13 | 17 | 5 |

| Min | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 72 | 24 | 21 |

| Average | 26 | 11 | 12 |

| Median | 26 | 8 | 11 |

Table 4. Funding Models Used By MiTTOs |

|

| External | 17 |

| Internal | 5 |

| Royalty share | 6 |

| Not Available | 2 |

| External plus Royalty | 5 |

Table 5. Benefits Of MiTTOs |

| Kick-starts member institutions in commercialization |

| Establishes a pro-commercialization culture immediately |

| Provides a critical mass of personnel and resources |

| Provides access to a greater skill set than individual member institutions could afford / justify |

| Makes services available at no or reduced cost to member institutions, reducing barrier to entry |

| Allows for aggregation of complementary technologies from different sources |

| Provides a focal point for lobbying the importance of tech transfer to government at an early stage |

Table 6. Challenges Encountered By MiTTOs |

|

Category |

Issue |

| Financial: | Scheduled expiration of funding |

| Unscheduled loss of funding | |

| Insufficient external funding to support operations | |

| Retained revenues inadequate to support operations | |

| Member institutions resent MiTTO’s retained revenue share | |

| Strategic: | Control – a natural transition from an external MiTTO to individual in-house TTOs |

| Lack of commitment to commercialization by member institutions | |

| Change in member institution’s objectives with respect to commercialization | |

| Unrealistic expectations by member institutions of the timelines for commercialization success | |

| Operational: | Member institutions’ researchers feel inadequate attention from MiTTO |

| MiTTO perceived as too selective in disclosures pursued / rejected | |

| Institutions keep the best disclosures to market themselves and send inferior ones to MiTTO | |

| Inadequate effort in training researchers, promoting commercialization and seeking out inventions | |

| Cultural: | Competition between MiTTO and research office established at member institutions |

| Conflict of values, culture and priorities between MiTTO and member institutions | |

| MiTTO too remote geographically from member institutions | |

| Inadequate communication from MiTTO to member institutions | |

| Member institutions feel inadequate ability to input into MiTTO personnel and operational choices | |

| Personnel in MiTTO lack pertinent qualifications and appropriate attitudes | |

| Researchers uncomfortable dealing with an external entity | |