We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

No cookies to display.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

No cookies to display.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

No cookies to display.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

No cookies to display.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

No cookies to display.

Véronique Blum

Associate Professor, University of Grenoble Alpes

Founder of StradiValue

France

Véronique Blum

Associate Professor, University of Grenoble Alpes

Founder of StradiValue

France Maxime Mathon

PartnerFigure

Ascend

Paris, France

Maxime Mathon

PartnerFigure

Ascend

Paris, FranceUnder the presidency of Ichiro Nakatomi, LESI has set the basis for a project titled “SDG IP-Index,” which was already described in the Part 1 article of this series: “LESI’s SDG-IP Index: Using Quality of Life Aspects—and Intellectual Property—as an Indicator of a Company’s Future Success” (Nakatomi et al., 2023). This second part exposes how the SDG-IP Index Committee1 approached the following question: how can we effectively capture the sustainability impact embedded in innovations? In order to address that issue, we opted for a qualitative analysis in a supplement to the quantitative analysis exposed in Part 1. Also, during the last LES Winter Planning Conference in Geneva, and in the same vein, someone raised their hand and asked, “By the way, what is ESG?” This article sheds light on those two questions and justifies the methodological choices made to build LESI’s SDG-IP Index.

This second part develops as follows: first, we come back to the roots of ESG-oriented investment to discover how ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) and SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) are two acronyms that resonate, yet that still seek paths for a better interconnection. Second, while data is perceived as instrumental for addressing SDGs, its current usage, and specifically in ESG ratings, has become controversial and insufficient to address the goals developed by the United Nations. Finally, we examine how combining IP and SDGs can be beneficial, and why LESI’S SDG-IP Index methodology includes a second layer.

1.1 The Rise of Awareness

The origin of Environmental (E), Social (S) and Governance (G) concerns remains fuzzy, but it certainly stems out of a series of U.S. initiatives, when ethical funds or funds managed by trade unions decided to focus on social progress as a means to foster growth. This took place a century ago, but a more radical change occurred in the 1960s and 1970s; it was a change of paradigm.

In 1962, Rachel Carson published “Silent Spring,” a lyrical and scientific study of the decline in biodiversity in Pennsylvania. For the first time, she observed that spring had become silent due to the collapse of populations of insects, birds, fish and even livestock, creating a threat to the entire food chain, up to human beings. This raises the further issue: how can we represent the effects of human activities on our planet? In 1966, Stewart Brand rephrased this question as follows: why have we still not seen a complete picture of the Earth? In other words, and in order to represent the impacts of our activities on Earth, it may be useful to share a common representation of the Earth. NASA responded to his request the following year with the release of a legendary snapshot described by some as “one of the most important photographs ever taken:” “Earthrise from Apollo 8” by William Anders, who commented, “We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered Earth.” The image of our Earth seen from space triggers an immediate and global awareness: our earth is vulnerable, in the middle of the void. Environmental awareness was then ready to grow. But the early social concerns are not forgotten. In 1970, the apartheid regime in South Africa fostered the need for Codes of Conduct such as the Sullivan principles of General Motors. Codes of conduct are soft, non-binding laws that set rules and that also avoided a complete disinvestment in South Africa.

1.2 Institutionalization of Environmental and Social Awareness

After half a century of increasing environmental and social awareness, the “responsible” movement was being institutionalized. In 1968, the first United Nations conference using the term “ecologically sustainable development” took place; it is the “Intergovernmental Conference for Rational Use and Conservation of the Biosphere” organized by UNESCO. The establishment by the OECD polluter pays principle (PPP) followed, with OECD adherents having to comply with the “Guiding Principles on the Economic Aspects of International Environmental Policies.” The same year, the first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) was held in Stockholm and the “Limits to Growth” report, also known as the Meadows Report was published.

It is in that context that a series of industrial accidents occurred that questioned the concept of responsibility: the Seveso industrial accident in Italy (1976), a series of shipwrecks and oil spills—Amoco Cadiz (1978, 1,600K bbl), SS Atlantic Express (1979, 2,015K bbl) Exxon Valdez (1989, 260K bbl)—the Three Mile Island accident (1979), followed by Chernobyl in 1985. In the midst of a high inflation period, taxpayers understood that they are the payers of last resort and brought pressure for more urgent responsible investments.

In 1987, the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development published its final report titled “Our Common Future” that included the first occurrence of the term “sustainable development.” The so-called “Brundtland” report argued that future generations will suffer from uncontrolled development: thus, “Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Five years later, in 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) was held in Rio de Janeiro. It brought together political leaders, diplomats, scientists, representatives of the media and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from 179 countries for a massive effort to reconcile the impact of human socio-economic activities on the environment. UNCED proclaimed the concept of sustainable development as an achievable goal for everyone around the world, whether at the local, national, regional or international level. It recognized that combining and balancing economic, social and environmental concerns in meeting our needs is vital to sustaining human life on the planet and that such an integrated approach is achievable if minds and hands work together. This included the need to re-think our lifestyles (production, consumption, coordination and decision-making).

1.3 Time for Action and Tools Development

Action followed the institutionalization period. In 1994, Elkington called for a Triple Bottom Line (TBL), i.e., a triple profit and loss end line, in order to capture social equity environmental practices as a supplement to the profit bottom line, also coined as “People, Planet and Profit.” However, if the initial idea means to encourage companies to manage their impact on people and the planet, many early users argued in favor of a compensation (doing harm to the planet is, for example, covered by financial profits), and find there an “alibi for inaction” (Elkington, 2018). To cope with its vulnerability, the TBL was later extended by the Triple Depreciation Line by Rambaud and Richard (2015).2

The same year, the Caux Roundtable produced a “simple, universal and voluntary commitment framework” based on the statement of the “Principles for Responsible Business.” Developed from the framework of the “Minnesota Center for Corporate Responsibility (MCCR),” they aimed to involve companies in global cooperation for the preservation of the environment. The voluntary and non-binding nature of the initiative encouraged the inauguration of a virtuous cycle that demonstrated exemplary behavior rather than being limited to compliance. It is on the basis of this work that the U.N. Global Compact issued its 10 Principles in 2000:

Also, in the year 2000, 193 Member States of the United Nations as well as 20 international organizations met at the Millennium Summit at the organization’s headquarters in New York. It is the largest gathering of heads of state and government of all time: 189 of them signed the Millennium Declaration,3 which set out the Millennium Development Goals for the period 2000-2015. They will serve as a framework for the construction of future Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The term ESG was coined in the 2004 report “Who Cares Wins,” which was intended to be the expression by the financial community of a set of recommendations for integrating CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility), as proposed by the UN Global Compact, within business lines: “asset management, securities brokerage services and associated research functions.”

This shaped the then-upcoming United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI) that sought to empower the shareholders of the largest global companies and to accelerate the adoption by companies of behavior compatible with sustainable development. UNPRI was launched with 100 investor signatures; there are currently 4,902, with about USD $121.3 trillion assets under management.

In 2010, experts from 99 countries produced the ISO 26000 standard that provided guidelines to help companies and organizations with their implementation of the principles of sustainable development. The text was approved by 93 percent of the participating countries with the exception of India, Luxembourg, Turkey, Cuba and the United States. Notably, ISO 26000 is not certifiable. This leaves room for other initiatives to flourish. In California, the B Corp label is one of the initiatives that fills the gap.

Finally, in 2015 and as part of the 2030 Agenda, the United Nations promoted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that superseded the Millennium Development Goals and constitute “a global call to action to eradicate poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people live in peace and prosperity by 2030.” With 17 holistic goals and 169 targets, the SDG agenda aspires to stimulate action in areas of crucial importance for humanity and the planet (United Nations, 2015). It is in this extension that on August 2, 2015, 193 countries adopted the 17 SDGs, issued by the UN Department of Social Affairs.

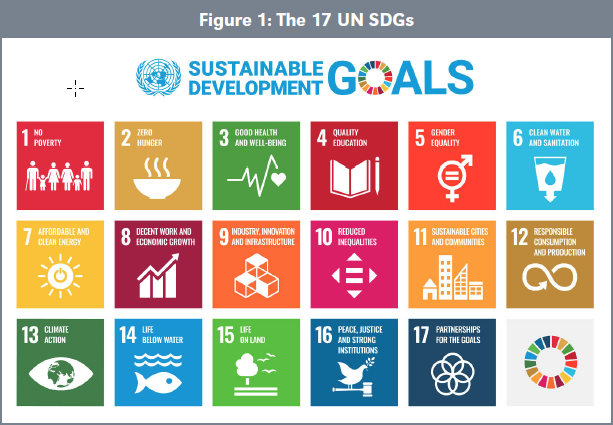

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals are: 1) Eradication of poverty; 2) Fight against hunger; 3) Access to healthcare; 4) Access to quality education; 5) Gender equality; 6) Access to safe water and sanitation; 7) Use of renewable energies; 8) Access to decent jobs; 9) Build resilient infrastructure and promote sustainable industrialization that benefits everyone and encourages innovation; 10) Reduction of inequalities; 11) Sustainable cities and communities; 12) Responsible consumption and production; 13) Fight against climate change; 14) Aquatic life; 15) Earth life; 16) Justice and peace; 17) Partnerships for achieving the goals.

With those 17 SDGs to be addressed (Figure 1, page 194), it appears that the current data abundance could support this endeavor.

2.1 The Promises of Data

Starting in 2005, Big Data unfolded, bringing with it new promises for understanding all kinds of phenomena, including sustainable development. Thanks to the availability of open source software, it is now possible to manage large amounts of data. In 2009, the United Nations launched an innovative laboratory, the UN Global Pulse, to better envision a world where responsible and inclusive digital innovation would advance sustainable development and protect the planet. The laboratory becomes a meeting place for digital innovation and human sciences. To anticipate, respond and adapt to future challenges, the UN Global Pulse brings together multidisciplinary teams from data sciences, strategic foresight, behavioral sciences and digital technologies.

In 2012, a first report “Big Data for Development: Challenges & Opportunities” specified how to fully integrate digital technology into the global strategy of the United Nations, which will lead to the creation, by Ban Ki-moon in 2014, of an independent group (Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable development, IEAG) responsible for putting Big Data at the service of sustainable development. This group of experts is behind the publication of the report “A World That Counts,” which precedes the publication of the SDGs.

The data revolution is expected to become a revolution for equality. Open data ensures that knowledge is shared, accessible and creating a world of informed and empowered citizens that are capable of holding decision-makers accountable for their actions.

With the creation of a “Global Data Ecosystem” based on a “Global Consensus on Data,” each country is expected to have the means to measure its progress towards sustainable development and to create the conditions for all empowered actors. An essential idea is the following: the global effort around sustainable development can only be effective if it is measured and measurable. Measurability becomes a necessary condition for transparency that allows the actors to align themselves. The United Nations thus takes data as the heart of the SDGs. To foster the movement, a list of categories of actors involved in the contribution to the SDGs was identified: the public/civil sphere (international organizations, national statistical agencies, ministries, territories and satellite programs, NGOs), the private sector (business) and the world of research (scientific and academic). Those multiple sources yet need to interconnect and measure overall progress, likely with novel approaches to data combination. This is the biggest challenge currently faced by scholars and practitioners and the role of instruments like the IP/SDGs award participate in that endeavor.

2.2 What Data Already Teaches Us

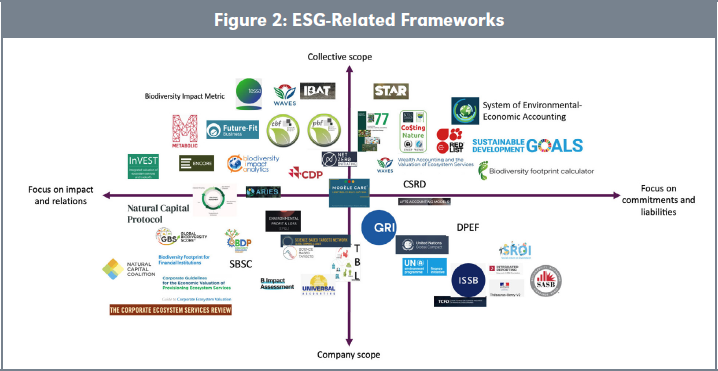

Before the adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Disclosure in Europe in January 2023, and which will be applicable in 2024, there exist no mandatory ESG standards that companies should apply to inform about their relationship with people and the planet. However, a long list of possible frameworks (initiatives) is available for companies desiring to serve sustainability goals. Blum and Russel (2022)4 identified more than 40 of them that they classified along two axes, depending on whether they address collective or entity-based goals, and on whether they appear in financial statements, or aim at testifying of commitments (Figure 2, page 195). Most of the frameworks are specialized on a particular topic (climate change, biodiversity, etc.). Amongst what is often coined an “alphabet soup,” a question follows: Which frameworks are adopted by companies in their corporate reports?

Many recent academic research works provide us with a deeper analysis on how often companies adopt those frameworks. Globally, although they differ in level estimations, they show a consistent picture of the preference for frameworks. They all converge in eliciting that the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI, founded in 1997), the SDG, and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD, issued in 2015) are the most used frameworks.

In its Sustainability Counts II report that surveys the 50 largest companies in 14 jurisdictions in the Asia-Pacific region, PwC observes that 78 percent of companies use SDGs as a framework for corporate reporting, while 81 percent refer to the (GRI), 69 percent use ISO, and 28 percent use UNGC.

Another survey conducted by IFAC5 (International Federation of Accountants) examines 1,350 companies across 21 jurisdictions, selected because they belonged either to the 50 biggest market capitalization of 15 jurisdictions or to the top 100 companies in the six largest economies (the U.S., Germany, the UK, China, India, Japan). Results show that 79 percent of the companies refer to SDGs, and 74 percent of them refer to GRI.

Shami (2023) examined a sample of 1,018 companies that belonged to more than 50 industries in 27 European countries (before Brexit), with at least 20 companies in each sector. Those were randomly drawn from the Eikon database. Thus, the sample includes relatively smaller size companies. His results suggest that 48 percent of the listed European companies mentioned some SDG in their annual reports. GRI again appears second with 31 percent of adopters, before the 21 percent of adopters of TCFD.

The narratives and quantitative information relating to the SDGs are included in different reports, according to jurisdictions. In the Americas, the preference goes to the sustainability report, with the exception of Brazil where integrated reports are favored. In Europe, the securities market authority encourages the publication of a Universal Registration Document (an exhaustive financial and extra-financial annual report) but it is not mandatory. In some jurisdictions, the sustainability report may be more exhaustive than the annual report.

3.1 ESG Raters: Who Are They?

Because ESG covers various areas of expertise, all remote from the usual financial know-how, intermediaries services providers have addressed the challenge of making the ESG information intelligible and useful to stakeholders. The most prominent service providers are ESG rating agencies such as MSCI, Eikon, S&P Global, DBRS Morningstar, ISS, London Stock Exchange Group and Moody’s ESG Solutions. The sector has dramatically shrunk in the past years, as a result of the consolidation of about 30 raters. The role of an ESG rating agency is very similar to that of a credit rating agency: it consists in providing a relative grade/score based on a series of indicators related to Environmental (E), Social (S), and Governance (G) metrics, or their aggregation (ESG). The sustainability metrics are most likely produced and aggregated in accordance with a proprietary. The ESG scores use the same substrate of public information, but also information collected through questionnaires or estimates made using proprietary algorithms. However, there is a significant difference between credit ratings and ESG ratings: if the first ones tend to converge across raters, the latter do not. Hence, recent research has scrutinized the important discrepancies between ESG rating agencies in order to explain those.

3.2 Divergence in ESG Ratings

A developing thread of research compares the ESG scores provided by various rating agencies in order to measure their divergences or convergences and explain those. Results concur in demonstrating the divergence in ratings. In their seminal work, Chatterji et al. (2009, 2016) demonstrated the lack of convergence between the six main social responsibility rating agencies. They pioneered a stream of academic research that has since then developed significantly and examined the consequences of the ratings divergences. Other authors pursue their work with the examination of a large number of ratings, whose names often changed due to the sector consolidation: KLD/MSCI Statts, MSCI, Asset 4/Refinitiv, S&P Global, Inrate, S-Ray/Arabesque, Truevalue Labs/Truvalue, IVA, Thomson Reuters/Eikon, Sustainalytics/ Morningstar, Moody’s/Vigeo Eiris, ISS, QS Investor, Bloomberg, Reprisk, Innovest, DJSI, FTSE4Good, Calvert, RobecoSam/S&P Global, and GES. Most studies examine correlation across ratings and break their analysis to the E, S or G levels or to the sector level; for example, Lopez et al. (2020) find that the energy sector experience a higher level of disagreement, whereas high levels of agreement among ratings are observable in activities such as financials, technology, and cyclical consumer goods and services.

Studies evidence several shortcomings of ESG ratings; some relate to the nature of the data, others to the construction of the rating instruments:

Close to the latter modeling issue, Berg et al. (2019) have observed a “rater effect,” describing the fact that a firm receiving a high score in one dimension is more likely to receive high scores in other dimensions.

3.3 The Constrained Reliance on ESG Ratings…

Berg et al. (2023) show that the individual scores of all rating agencies significantly correlate with the holdings of ESG funds in the U.S. (ESG ownership), with MSCI’s score showing the highest correlation coefficient, which is persistent and increasing over time. The authors examined a sample of 3,665 listed U.S. corporations, with 4,679 rating changes that take place between February 2013 and September 2020, and show that ratings downgrades lead to an abnormal return of -2.37 percent, whereas upgrades have a positive but weaker effect. Hence, ESG information has become instrumental in investment decision-making. LaBella et al.’s analysis (2019) further shows that there is less risk among companies that scored higher on ESG metrics. Those facts evidence that the market is pricing in company-specific ESG risk. Hence, despite the imperfections of the available ESG ratings, and knowing that initial data is seldom accessible (Blum and Mathon, 2023), ESG ratings remain the main source of sustainability diagnosis.

More surprisingly, ESG disagreement seems to be an advantage for some companies. Gibson et al. (2021) show that equity returns and ESG rating differences between the various agencies are positively correlated. Thus, the greater the disagreement between the ratings, the higher the profitability. Christensen, Serafeim, and Sikochi (2021) also demonstrate that the higher the number of data points published by companies, the higher the discrepancies across ratings. However, some high sustainability performance also results from an inflation of the ratings that they assign to companies (Bams & Van der Kroft, 2022). The authors even add that “Refinitiv, MSCI, and FTSE ESG ratings are inversely correlated with sustainable performance.”

It follows that in the absence of a clear view, and in the absence of ESG information standards, there remains for significant “greenwashing” that can lead to misallocation of capital and missed opportunities (Antoncic, 2021).6 To assess the effective impact of companies, responsible investors resort to a set of ESG rating providers that collects, gathers, estimates and processes ESG data provided by the rated companies or other external sources of information. Why do investors rely on multiple ratings?

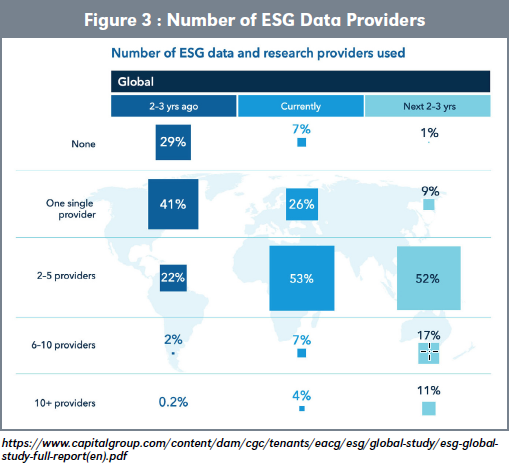

As a consequence of those imperfections and inefficiencies, more and more responsible investors now resort to several providers. Figure 3 shows the result of a survey of 520 global institutional investors (pension funds, family offices, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, endowments and foundations) and 520 global wholesale investors (funds of funds, discretionary fund managers, private banks, broker/ dealers, registered investment advisors, independent advisories and investment divisions of insurance). The multiple procurements are a direct consequence of the lack of harmonization of global standards, taxonomies and metrics, something that 45 percent of the surveyed practitioners deplore.

3.4 …to Assess the Reach of SDGs

Recent research by Bekaert et al. (2023) establishes a positive connection between a portfolio’s ESG ratings momentum and its SDG footprint. Hence, the authors suggest that there exists a positive relation between ESG ratings (and thereby their components) and the portfolio’s SDG footprint. In order to measure the SDG footprint, the authors use Global AI Corp.’s (GAI) SDG scores. The score uses artificial intelligence to extract, screen and clean considerable amounts of structured and unstructured data. This includes self-reported company data, press and blog articles, NGO communication and surveys, and unstructured social media information. The data is collected in more than 100 countries and in 60 languages. Artificial intelligence algorithms map this large variety of data to associate it with companies and their subsidiaries. Combinations are driven thanks to company names, tickers, and ISINs. The output consists of 17 SDG scores for each company, and a score measuring the overall SDG footprint of a company. The scores reflect sentiment or SDG fitness.

This approach is in line with the work from Kimbrough et al.( 2022) who show that voluntary ESG reports resolve disagreement among ESG raters. Using textual analysis, authors show that longer (more disclosure), less positive (better textual quality), and less sticky ESG reports contribute to reducing disagreement among ESG raters. This also improves when firms obtain assurance from accounting firms. In the same vein, Shami (2023) shows that companies referring to double materiality tend to display less disagreement in their ESG ratings.

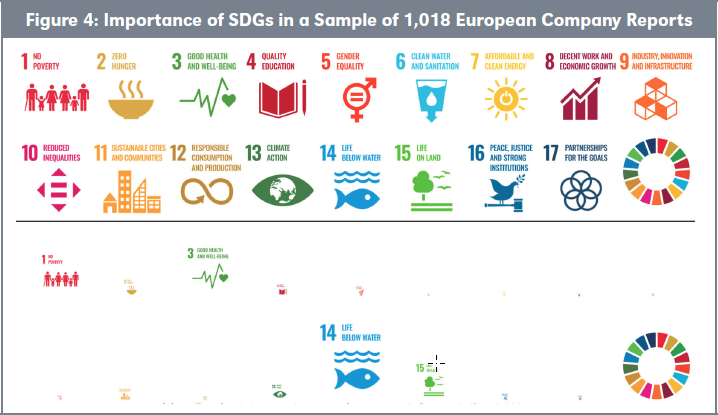

It is indeed relevant to break down the footprint for each of the 17 goals, as companies unequally communicate about those. Blum and Russell (2022) have examined the data collected by Shami (2023) to represent the presence of the 17 SDGs in companies’ reports. In 2020, SDG number 14—Life Under Water—was the most cited in the examined sample of 1,018 companies (Figure 4). This can be explained by the global abandonment of plastic packaging that is aimed at reducing the amount of plastic that finds its way to the ocean. In our figure, the relative size of SDG14 is used as a benchmark, and the size of the other SDGs are proportional to their relative comparable presence in companies’ reports.

3.5 ESG, SDGs and Innovation

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) is also of the following opinion: “Intellectual property is an essential driver for innovation and creativity which, in turn, are necessary for the success of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations. The examples of solutions imagined by inventors, companies and other organizations to meet social, economic, health and environmental challenges are powerful reminders of our collective capacity to achieve the SDGs and the role that intellectual property rights play in achieving this.” 7 The SDGs, linked to innovations, provide a goal to “build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialization and foster innovation.” WIPO’s former Director General Francis Gurry highlighted the relationship between the two and said that intellectual property “exists to create an enabling environment and to stimulate investment in innovation.”.8 WIPO has identified that innovation is key to meeting SDGs 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 11 and 13, while SDG 9 directly addresses innovation.9 Furthermore, the HRC and WIPO, in their joint publication, i.e., “IP and Human Rights,” have concluded that “appropriate protection of intellectual property can contribute to the economic, social and cultural progress of the diversity of the world’s population.”

Also, given the critical importance of the SDGs, the UN initiative has attracted considerable attention in policy debate and research in academia (for a meta literature review, see Pigatto et al., 2022). However, despite a call for researchers (Bebbington and Unerman, 2018), the academic literature on corporate reporting remains very limited relative to SDG-related research in disciplines other than financial reporting (Bebbington and Unerman, 2020).

Beyond Global AI’s tools that we exposed herein, new tools are developing that approach capturing these impacts in a different manner than ESG ratings do. For example, InTraCom examines the relationship between sustainability goals and intellectual property,10 and LexisNexis maps patents that are explicitly related to the targets and indicators mentioned in SDGs in order to assess the sustainability compliance of entities from the perspective of patents.

LESI’s SDG-IP Index addresses those gaps. Considering the limited scientific knowledge relative to the link between innovation, sustainable development and SDGs, and aware of the risks induced by data and rating models’ inconsistencies, it was important to the committee that the identified and here before exposed pitfalls in data manipulation were avoided. It is in that mindset that the SDG-IP Index Committee decided not to rely exclusively on quantitative data.

Hence, the SDG-IP Index is built in two stages: 1) a quantitative process described in Nakatomi et al. (2023) was employed as a first filter, and 2) a qualitative assessment refines the findings and verifies their robustness.

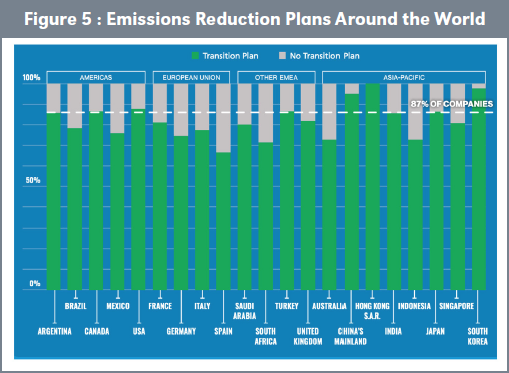

To circumvent possible greenwashing in reported and declarative information, the committee reunited several times during the winter 2022/2023 to identify methodological means to address the issue. The committee opted for an extended collection of information that aims at testifying to an effective ESG/SDG impact concern. The committee identified surveys in the form of interviews as the most appropriate approach to collect the required data. Because this is time-consuming and there is a will not to add to the burden of the multiple raters, the survey is only directed to companies that were well ranked in the quantitative stage of our selection. The questionnaire (see below) includes several themes in 24 questions: i) the existence of an alignment between R&D or R&I and SDGs, and the demonstration of proofs of such an alignment (in the budget, number of projects, the use of indicators or models targeting the SDG), ii) the link between IP strategy and SDGs, and iii) the link between IP exploitation and SDGs. Weights are associated to those dimensions. They were allocated on the basis of the committee members’ relative perceived importance of each item after conducting pair comparisons. Notably, some of the questions survey the existence of baseline or roadmaps or trajectories. Indeed, it is now generally accepted that only baseline must constitute a reference point to an improved reduction of the impact on people and the planet, where a roadmap indicates some reflections and the existence of an action plan likely to allow the company to achieve its goals. Nevertheless, this point of attention is not expected to exclude companies: according to IFAC (2023), on average, 87 percent around the world have a transition plan with respect to emissions (Figure 5).

| The Qualitative SDG-IP Index Questionnaire | |||||

| (1) | Best | Strong | Intermediate | Low | |

| Link Between R&I And SDG Strategy | |||||

| How much is your R&D/R&I aligned with your SDG strategy? | 1 | Fully 4 |

Strongly 3 |

Half 2 |

Moderately 1 |

| % of R&D budget spent on projects contributing to one or several SDG goals | 1 | 90% 4 |

70% 3 |

50% 2 |

30% 1 |

| % of R&D projects contributing to SDG goals | 1 | 90% 4 |

70% 3 |

50% 2 |

30% 1 |

| Do you use a scoring model to rank your R&D projects according to their societal and environmental impacts/alignment with SDGs? | 4 | Yes 1 |

Yes 1 |

Yes 1 |

No 0 |

| What is the share of projects selected according to that ranking ? | 1 | 100% 4 |

80% 3 |

60% 2 |

40% 1 |

| Do you use individual project indicators explaining which SDG the projects help attain? | 2 | Yes 1 |

Yes 1 |

Yes 1 |

No 0 |

| In case the answer to the previous question is “yes,” how many indicators do you use? | 0.5 | >3 4< |

2 or 3 3 |

1 2 |

0 1 |

| Are there other procedures in your company to identify or link SDGs to its R&D projects? | 2 | Yes 1 |

Yes 1 |

Yes 1 |

No 0 |

| In case the answer to the previous question is “yes,”please describe | 0.5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| How do you measure the commercial, societal and environmental impacts of your R&D/R&I? | 1 | Through a specialized 3rd party 4 |

Internally, quantitatively 3 |

Internally, qualitatively 1 |

(Mostly) Not measured 0 |

| Link Between IP Strategy And SDGs | |||||

| How do you manage your IP with SDG potential? | 1 | We protect by patents 4< |

We protect as trade secrets 3 |

We publish and promote 2 |

We publish 1 |

| When protecting your IP by patents, do you take the SDG potential of your IP into account when selecting its geographical scope of protection ? (e.g., filing patents in Africa) |

1 | We systematically obtain and maintain IP in SDG relevant territories. 4 |

Only if additional cost is minimal 2 |

Not at all 0 |

|

| If you decide not to protect IP by patents in SDG-relevant jurisdictions, would you still consider valorizing it there? | 1 | We systematically look for alternative ways of protection in those jurisdictions. 4 |

Maybe as a trade secret 2 |

No because it cannot be valued anymore 0 |

|

| Do you repurpose (some of) your IP to attain SDG goals? | 1 | This is part of our SDG evaluation strategy 4 |

Only if the original IP is not compromised 3 |

Only if suggested by stakeholder 2 |

Never 1 |

| Do you ensure equitable access to IP protection to women inventors? | 0.5 | It’s one of our strategy points 4 |

Sometimes 3 |

Only if required by stakeholder 2 |

Never 1 |

| Do you pay special attention to the respect of grassroots inventors and creators? | 0.5 | It’s one of our strategy points 4 |

Sometimes 3 |

Only if required by stakeholder 2 |

Never 1 |

| Link Between IP Exploitation And SDGs | |||||

| How do you make a useful IP available? | 3 | Via impact licensing through an independent Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) 4 |

Via external licensing to arm’s-length third parties 3 |

Only via internal licensing to local affiliates 2 |

Publishing (and promotion) 1 |

| Grant of exploitation rights made conditional to commitments in terms of gender equality, human rights and inclusion? | 1 | Yes and check by independent 3rd party 4 |

Yes and check by yourself 3 |

Yes, included in the agreements 2 |

No 0 |

| Grant of exploitation rights associated to commitments in terms of working conditions | 1 | Yes and check by independent 3rd party 4 |

Yes and check by yourself 3 |

Yes, included in the agreements 2 |

No 1 |

| Criteria: % Licenses with SDG contractual obligations for licensees | 3 | 80% 4< |

60% 3 |

40% 2 |

20% 1 |

| How do you differentiate the SDG goals in your licensing fee strategy | We license out for free to an SPV with the right o sublicense against a fee. 4 |

We license out to a third party at a lower fee ith the right to sublicense. 3 |

We charge a lower fee for SDG beneficiaries. 2 |

We charge the same fees 0 |

|

| How much of your SDG-IP is licensed out to 3rd parties? | 1.5 | 80% 4 |

60% 3 |

40% 2 |

20% 1 |

| Do you license out IP facilitating circularity, decreasing resource consumption, decreasing CO2 emissions, decreasing impact on biodiversity, increasing the use of green energy? | 1 | Systematically 4 |

Often 3 |

Sometimes 1 |

No 0 |

| Licensing-in strategy: Do you select technologies according to SDG criteria? | 1 | Systematically 4 |

Often 3 |

Sometimes 1 |

No 0 |

| Authors: Andreas Zagos, Bruno Vandermeulen, Thierry Van Beckhoven, Véronique Blum. | |||||

The main conclusion from this second entry in the series is that the assessment of sustainable IP value can only be properly assessed when one collects supplemental qualitative data. Because ESG ratings are not a reliable solution, and declarative information can be biased, a qualitative assessment has to be conducted. The data is collected thanks to surveys that cover and seek evidence of effective integration of SDGs as piloting tools and, moreover, with references to baselines, roadmaps or targets. Our dual approach makes the LESI SDG-IP Index a unique measure of companies’ sustainability and innovation performance and impact. A third entry to this series of articles will cover concrete examples of the application of our Index.

Antoncic, D. M.,“Is ESG Investing Contributing to Transitioning to a Sustainable Economy or to the Greatest Misallocations of Capital and a Missed Opportunity?,” Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions, 15 n°1, (2021), 6–12.

Bebbington, J., & Unerman, J., “Advancing Research into Accounting and the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33, n°7(2020): 1657–1670.

Bebbington, J., & Unerman, J., “Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals,” Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31, n°1 (2018): 2–24.

Bekaert, G., Rothenberg, R., & Noguer, M., “Sustainable Investment—Exploring the Linkage Between Alpha, ESG, and SDGs,” Sustainable Development, (2023): 1– 12.

Berg, F., Fabisik, K., Sautner, Z., “Is History Repeating Itself? The (Un)Predictable Past of ESG Ratings,” European Corporate Governance Institute—Finance Working Paper 708/2020 (2021).

Berg, F., Heeb, F. and Kölbel, J., “The Economic Impact of ESG Ratings” (2023) Available at SSRN: https:// ssrn.com/abstract=4088545.

Berg, F., Lo, A., Rigobon, R., Singh, M., Zhang, R., “Quantifying the Returns of ESG Investing: An Empirical Analysis with Six ESG Metrics,” MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 6930-23 (2023b).

Berg, F., Kölbel, J., Rigobon, R., “Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings,” Review of Finance, 26, n°6 (2022): 1315-1344.

Blum, V., Mathon, M., “Le Numérique au Service d’un Futur Durable (Digitization for a Sustainable Future),” Digital New Deal, (2023) Forthcoming.

Blum, V., Russell, S. “Regards sur les Comptabilités ‘Vertes’ Actuelles, Proposition d’un Grille d’Analyse,” Programme de Recherche Économie & Société, Entreprises Humaines : Ecologie et Philosophies Comptables, Collège des Bernardins et Agro-ParisTech (2022).

Capizzi, V., Gioia, E., Giudici, G., Tenca, F., “The Divergence of ESG Ratings/an Analysis of Italian Listed Companies,” Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions, 9, n°2 (2021): 21p.

Elkington, J., “25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase ‘Triple Bottom Line.’ Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It,” Harvard Business Review Digital Articles, (2018):2–5.

Kimbrough, M. D., Wang, X., Wei, S., Zhang, J. (Iris). “Does Voluntary ESG Reporting Resolve Disagreement Among ESG Rating Agencies?,” European Accounting Review, 1–33 (2022).

Kotsantonis, S., Serafeim, G., “Four Things No One Will Tell You About ESG Data,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 31, n°2 (2019): 50-58.

LaBella, M., Sullivan, L., Russell, J., Novikov, D., “The Devil is in the Details—Divergence in ESG Data,” QS Investors, ESG Investing (2019): 11p.

Lopez, C., Contreras, O ; Bendix, J., “ESG Ratings: The Road Ahead,” (2020) Available at SSRN: https://ssrn. com/abstract=3706440 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ ssrn.3706440.

Nakatomi, I., Zagos, A., Colarulli, D. “LESI’s SDG-IP Index: Using Quality Of Life Aspects And Intellectual Property As An Indicator Of A Company’s Future Success (Part I),” les Nouvelles (March 2023).

Rambaud, A., Richard, J., “The Triple Depreciation Line Instead of the Triple Bottom Line: Towards a Genuine Integrated Reporting,” Critical Perspectives on Accounting. 33 (2015): 92–116.

Shami, A., “Double Materiality: From Theory to Practice,” CSEAR Montpellier, (June 2023).

Stackpole, B., “Why Sustainable Business Needs Better ESG Ratings,” MIT-Ideas that matter (2023).

Widyawati, L., “Measurement Concerns and Agreement of Environmental Social Governance Ratings,” Accounting & Finance, 61 (2021): 1589–1623.