We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

No cookies to display.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

No cookies to display.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

No cookies to display.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

No cookies to display.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

No cookies to display.

Toshifumi Futamata

Visiting Senior Researcher

The University of Tokyo, Institute for Future Initiatives

Tokyo, Japan

Toshifumi Futamata

Visiting Senior Researcher

The University of Tokyo, Institute for Future Initiatives

Tokyo, Japan Kaname Matsumoto

Director of Sub-Division

Third Patent Examination Department, Japan Patent Office

Tokyo, Japan

Kaname Matsumoto

Director of Sub-Division

Third Patent Examination Department, Japan Patent Office

Tokyo, JapanThe essence of standard-essential patent (SEP) disputes boils down to how to distribute the new value created by SEPs in the newly emerging business ecosystem in various fields. To resolve this difficult issue, which oscillates between right holders and implementers, R&D incentives and market expansion, various attempts have been made by standard-setting organizations (SSOs), judicial authorities, competition authorities, arbitration bodies, and administrative bodies around the world to find a resolution mechanism. The number of lawsuits over SEPs in various countries has increased year by year, and efforts have been made to find a solution in the process.

Many disputes over SEPs have arisen mainly in the mobile telecommunications sector.1 However, with the advent of the 5G era, as various goods and services become even more connected and use cases explode, many companies have entered the market and their conflicts are expanding and becoming more complex. In addition, due to the industrial structure of each country, aspects that directly affect national interests among countries have come under close scrutiny.

For example, in the basic conflict structure between a company that develops communication technology or communication modules (patentee) and a communication terminal manufacturer that incorporates the technology (licensee), the nationality of the company is rarely discussed, and many disputes between companies in the same country have taken place. In the U.S. and Europe, there are companies on both the patentee side and the licensee side. However, with the growing presence of Chinese companies in the IT field, such as the participation of Chinese telecommunication equipment manufacturers in IoT home appliances and connected cars with the development of 5G, SEP disputes involving Chinese companies have become more frequent in countries around the world, including China. And disputes over jurisdiction in parallel litigation between courts in different countries have emerged as a new point of contention in SEP disputes.

SEPs are born out of the standardization activities of international SSOs, and their global nature has led to disputes in many countries, with the jurisdictional disputes that occurred frequently around 2020 attracting attention as a new point of contention. What triggered the discussion was the Anti-Suit Injunction (ASI)2 that was introduced by China, which is an extremely powerful defense mechanism in SEP litigation. China’s aggressive adoption of the ASI has created a new global governance competition between states in SEP disputes.

An ASI is an interim remedy issued by a court in one jurisdiction to prohibit a litigant from commencing or continuing a parallel action or applying for enforcement of a judgment in another jurisdiction or territories. Originally a common law concept originating in medieval England,3 the concept has been elaborated in the United States and has been utilized by courts as a means to deter parallel litigation, eliminate duplication of judgment, and lead to a comprehensive resolution while modestly considering the merits of the case. It has also been applied to international litigation in common law countries with broad jurisdiction, as represented by the U.S. doctrine of the long arm and has been treated in a delicate balance based on the principle of international comity and the doctrine of forum non conveniens as a means of curbing forum shopping. The Court has also applied the principle of international forum shopping as a means of curtailing forum shopping. Although there have been occasional disputes over the merits between common law states and continental law states that do not have the concept of ASI, it has never been a major international issue.4

However, in SEP disputes in recent years, which are often global in nature, there have been cases where the U.S. and U.K. courts have upheld ASIs and the German and French courts have issued Anti-Anti-Suit Injunctions (AASIs) in parallel litigation in response. For example, in the Microsoft v. Motorola case (2012),5 an ASI was issued by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington against a motion for an injunction in a patent infringement lawsuit filed by the German District Court of Mannheim in a parallel lawsuit in which a violation of the FRAND obligation was challenged. Other examples include TCL v. Ericsson (2015),6 wherein a multi-country ASI was issued by the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California; and Nokia v. Continental (2019), in which an AASI was issued by the German District Court in Munich against an ASI filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, and IPCom v. Lenovo,8 in which the French Court of First Instance in Paris and the English Court issued an AASI against an ASI filed in the U.S. Northern District Court of California (2019).

ASIs were then extended to China. Two cases are important to understand the background of ASI in China. The first case is the Unwired Planet v. Huawei case,9 which was the direct trigger for the subsequent outbreak of Chinese ASI, and the Conversant v. ZTE/ Huawei case, which was tried together with this case. The case made headlines in 2017 when the U.K. High Court ruled that the global FRAND rate could be determined and was upheld by the Court of Appeals and the country’s Supreme Court in 2020. In its decision, “This Court finds that the English courts have jurisdiction and can properly exercise these powers. Questions of domestic patent validity and infringement shall be referred to the courts of the country that granted the patent. However, the contractual arrangements made by ETSI under its IPR Policy give English courts jurisdiction to determine the terms of licenses for patent portfolios containing foreign patents.”

For example, when attempting to file a parallel lawsuit regarding royalty confirmation outside the U.K., a penalty such as an injunction in the U.K. based on a U.K. patent will be imposed. The fact that SEP global FRAND including China, despite 64 percent of Huawei’s sales coming from China or countries where Unwired Planet does not hold patents while the U.K. market accounted for only 1 percent of Huawei’s sales, that the rate has been fixed by an U.K. court, and that Huawei10 and ZTE11 were forced to withdraw or amend their parallel lawsuits in China due to ASI being virtually accepted in the course of the lawsuits had a great impact on Chinese concerned people.12

The second case is the 2018 Huawei v. Samsung case.13 In this case, contrary to the U.K. case, although Huawei, a Chinese company, obtained a ruling from the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court in China granting its request for an injunction in its capacity as the SEP right holder, in a parallel lawsuit in the U.S., the U.S. Northern District Court of San Francisco issued an ASI based on Samsung’s motion to prohibit Samsung from applying to enforce the above Chinese judgment. This case became a hot topic in China as a case in which the enforcement of a patent right in China was prevented by the U.S. ASI.

The Supreme People’s Court of China listed these cases in its commentary on the first ASI (“Jin-Su-Ling”) in China’s intellectual property lawsuits, which will be described later, stating, “Based on the deterrence of the injunction issued by the courts of other countries, the parties withdrew their lawsuits in China, or it has been partially withdrawn.” Chinese concerned people began considering the application of the ASI to the Chinese judiciary around 2018, when the rulings (including lower courts) on the above two cases were issued, and were closely watching developments in the U.S., U.K., Germany, and France.14 Then, in May 2020, Luo Dongchuan, President of the Intellectual Property Court of the Supreme People’s Court, stated at the National People’s Congress, “With IP becoming the focus of international competition, the rules of international jurisdiction in foreign-related IP litigation proceedings in China are not clear, so we will expand the application of the act preservation system to realize the function of “Jin- Su-Ling” and counter-“Jin-Su-Ling” and form a strong countermeasure against foreign parallel lawsuits.”15

3.1 Birth of the First “Jin-Su-Ling” and its Background

The first ASI (“Jin-Su-Ling”)16 in Chinese IP litigation was the Supreme People’s Court’s August 28, 2020 ruling granting the petition for maintenance of conduct in the Huawei v. Conversant case.17 The ruling, issued the day after the petition was filed, prohibited Conversant from applying for an injunction under the August 27, 2020 Düsseldorf District Court decision18 regarding a patent infringement lawsuit between the same parties, based on the “maintenance of conduct” provision under the Code of Civil Procedure.19 It is also important to note that the court introduced a hefty penalty for failure to comply with this ruling, a fine of RMB one million per day, to be accumulated daily from the date of violation.

As between these parties, in January 2018, prior to the filing of this German lawsuit (April 2018), a lawsuit was filed by Huawei with the Nanjing Intermediate People’s Court to confirm non-infringement and license fees for the SEPs to which Conversant is entitled. In September 2019, the Nanjing Intermediate People’s Court ruled to invalidate some rights and to approve the license fee rate for some rights (China’s first “top-down approach” to FRAND royalty approval). Huawei continued to file the pending China lawsuits based on the “act preservation” provision under the Civil Procedure Law. Huawei filed a “Jin-Su-Ling” with the Supreme People’s Court on the same day that the German District Court decision20 was issued, based on the “act preservation” provision under the Civil Procedure Law. This preservation of conduct is required by the Code of Civil Procedure to make a ruling “within 48 hours” from the filing of the petition if the situation is deemed urgent, and in fact, the ruling was made on the day following the filing of the petition in a procedure (ex-parte) involving only one party.

The reasons for the decision were not disclosed by the Supreme People’s Court until six months later in February.21 The Supreme People’s Court established five norms for ASI: (1) the effect of provisional enforcement of extraterritorial judgments on Chinese litigation, (2) the necessity of adopting action preservation measures, (3) the balance of profits and losses, (4) harm to the public interest, and (5) the principle of international comity.

Then the court applied the circumstances of this case to each item and ruled as follows: (1) The parties to both litigations are the same, the subjects of both litigations are also partially the same, and that Conversant’s request for enforcement of the injunction in Germany will affect the litigation and enforcement of the judgment in China. (2) If the ASI is not issued, Huawei will have no choice but to withdraw from the German market or accept a license offer from Conversant, and Huawei will suffer unbearable damage. (3) The central interest of the German litigation is to obtain economic compensation and the effect of the injunction is only a delay in the execution of the German judgment for Conversant. Moreover, Huawei has already provided security. Therefore, Huawei’s damage if the ASI is not issued far exceeds Conversant’s damage if the ASI is issued. (4) Since this case only concerns the interests of Huawei and Conversant, it does not harm the public interest. (5) Generally speaking, it is necessary to protect the country’s judicial sovereignty, security, and core interests, and to give due consideration to the national interests of the partner country. In this case, the Chinese litigation was accepted before the German litigation, and the ASI does not affect the progress of the German litigation and the legal validity of the judgment, which is consistent with the principle of international comity.

3.2 Subsequent Series of Injunctions by Lower Courts in China

The Huawei v. Conversant decision of August 28, 2020, was selected by the Supreme People’s Court as one of the “Ten Major Cases of the People’s Court in 2020,”22 “Ten Major Technological Intellectual Property Cases in 2020,”23 and “Ten Major Intellectual Property Cases of the Chinese Court in 2020.”24 The case was positioned as a normative case in the judgment of “Jin- Su-Ling.” After this ruling, a series of “Jin-Su-Ling” were issued by lower courts in China.25 At the time of this writing, the Supreme People’s Court has issued “Jin-Su- Ling” only in the Huawei v. Conversant case. Others have been issued in the Sharp case (October 2020),26 the ZTE v. Conversant case (August 2020), and Lenovo v. Nokia case (dismissed in January 2021)27 in Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court, and the Xiaomi v. InterDigital case (September 2020)28 and Samsung v. Ericsson case (December 2020)29 for a total of six cases identified (see Table 1 on page 11, which also lists global FRAND rate jurisdiction disputes and other cases closely related to the ASI cases).

China’s “Jin-Su-Ling(禁诉令)” can be divided into two types. The first type is “Jin-Zhi-Ling(禁执令),” which prohibit only applications for enforcement of specific foreign judgments, such as the Huawei v. Conversant and ZTE v. Conversant cases. The second type prohibits not only the applications for enforcement, but also filing new lawsuits concerning infringement injunctions and SEP license terms, and new ASIs and AASIs all over the world. For example, the Xiaomi v. InterDigital, Samsung v. Ericsson, and OPPO v. Sharp cases fall into this type. This type is also unique in that it is combined with a lawsuit seeking to establish global FRAND rates. In addition, the two cases at the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court are extremely wide-ranging, even ordering the withdrawal or suspension of foreign infringement lawsuits, ASIs, and AASIs that have been filed so far. The reason for the difference between the first and the second types is that, excluding the difference in the content of the claims made by the parties, in the first type, the first ASI judgment by the Supreme People’s Court, which has de facto normativeness, and carefully considers factors such as international comity and damages to the parties, but in the second type, although the Intermediate People’s Court followed the decision of the Supreme People’s Court on (2) and (3) in section 3.1 above for Huawei v. Conversant as a factor to consider, it can be read from the judgment text that the analysis was rough and made with the predetermined conclusion.

In addition, as the basis for the issuance of the ban on prosecution by China, one of the points is whether the Chinese lawsuit or the foreign lawsuit was accepted first. In the Huawei v. Conversant case, the Supreme People’s Court held that the Chinese lawsuit was filed before the German lawsuit as one of the grounds for issuing an injunction against the motion to enforce the German judgment. In Xiaomi v. InterDigital and Samsung v. Ericsson, the Chinese lawsuit was filed first, and in the former case, the Supreme People’s Court even found “bad faith” on the part of InterDigital in filing the foreign lawsuit with knowledge of the Chinese lawsuit. However, in the OPPO v. Sharp case, parallel lawsuits were filed in Japan (Tokyo District Court) and Germany (Munich and Mannheim District Courts) prior to the China lawsuit, indicating that consideration was given to the principle of international comity by prohibiting only the filing of new lawsuits, “Jin-Su-Ling,” and counter-” Jin-Su-Ling.” This case shows that the filing of a Chinese lawsuit prior to a foreign lawsuit is not a necessary condition for the issuance of a “Jin-Su-Ling,” but it does affect the decision on its admissibility.

Here, we would like to mention the Lenovo v. Nokia case, which is the only case in which the “Jin-Su-Ling” has been dismissed at this time. In this case, the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court denied Lenovo’s motion for an ASI in January 2021 on the grounds that the court had not yet issued judgments on parallel lawsuits in Germany, India, Brazil, and other foreign countries, that Lenovo had a chance of winning its case, or that the case could be settled through arbitration, and that the damage caused by not issuing ASI could not be assessed. The court denied Lenovo’s motion for the ASI.

3.3 Overseas Reactions

In response to a series of “Jin-Su-Ling” issued in China, a series of AASIs were issued by courts in Germany, the U.S., India, and other countries. For example, in the InterDigital v. Xiaomi case,30 the Munich District Court of Germany issued AASI and AAAASI against the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court’s “Jin-Su-Ling” (equivalent to ASI and AAASI), as well as the European Standard Essential Patents. The court even stated that Xiaomi’s application for an injunction in China would not be treated as a “willing licensee,” which is a key factor in determining whether or not to grant an injunction in a dispute over a standard essential patent in Europe. This is in direct conflict with the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court’s finding of “bad faith” in Inter- Digital’s lawsuit in another country. Furthermore, the court even granted a precautionary AASI application in anticipation of the filing of parallel lawsuits and ASI petitions in other countries with China in mind (i.e., at a stage when parallel lawsuits have not yet been filed in China). For example, the Munich District Court of Germany in IP Bridge v. Huawei granted AASI (2021),31 the Düsseldorf District Court of Germany in HEVC v. Xiaomi granted AASI (2021),32 and the U.K. High Court in Philips v. Oppo granted AASI (2022),33 affirmed by the U.K. High Court in the case of Philips v. Oppo.

If ASI is issued, the fine is one million yuan (20 million yen) per day in China, and in other countries, for example, 200,000 euros (27 million yen, IPCom v. Lenovo case) per day in France. AASI exchanges pose significant economic risks for both parties. Therefore, all of the six cases in which ASI was challenged in China resulted in early settlements. While some in China positively evaluated the ASI as having the effect of facilitating settlements, others remained negative about the ASI as forcing foreign firms to settle under extremely unfavorable conditions.

Against this backdrop, concerned about a series of lawsuits over ASI, European industry participants approached the European Commission. First, on July 6, 2021, the European Commission filed a request with the WTO under Article 63 “Ensuring Transparency” of the TRIPS Agreement, requesting disclosure of information on China’s ASI case. The Commission claimed that only the “Jin-Su-Ling” ruling text in the Huawei v. Conversant case was available on the Chinese government’s official website, China judgments online (中国裁判⽂ 书⽹).34 In response, the Chinese government submitted a response dated September 7 of the same year,35 stating that China was not obliged to respond under the TRIPS Agreement. In response, on February 18, 2022, the European Commission filed a WTO dispute settlement complaint against the Chinese government on the grounds that the Chinese government was pressuring patentees who had filed lawsuits outside China to settle for below-market license fees through “Jin-Su-Ling” and fines, thereby unfairly restricting the enforcement of patent rights by EU companies. A request for consultations under the procedure was subsequently filed.36,37 Following this request for consultations, Japan, the U.S., and Canada requested third country participation.38 The Chinese government’s Ministry of Commerce expressed regret on the day of the consultation request.

In the United States, ASI has further become a political issue in the composition of the U.S.–China confrontation. The U.S. Trade Representative’s (USTR) Special Section 301 Report for 2021 and 2022,39 with China’s prohibition of lawsuits in mind, discussed the broad prohibition on asserting rights in the world as well as the prohibition on the enforcement of certain foreign lawsuits, and the concerns of rights holders about high fines. The report mentioned General Secretary Xi Jinping’s comments on the application of the law, as well as the relationship between the CCP and the courts. Also, on March 8, 2022, bipartisan legislator(s) introduced a bill to limit enforcement of ASI issued by foreign courts, including China, on the grounds that China is attempting to interfere with patent litigation in the U.S. in an effort to steal U.S. technology and to have Chinese courts resolve IP disputes worldwide. The Defending American Courts Act has been introduced in the Senate.40 The bill includes, among other things, that a finding of patent infringement by a party asserting an ASI in a foreign country would be presumed to be willful and subject to punitive damages.

3.4 The Nature of the Problem of ASI in China

The direct impetus for the Chinese ASI was what China viewed as an infringement of its own sovereignty with respect to the ASI and global FRAND rate judgments by the U.K. and the U.S. against Chinese companies and by courts in other countries. However, we believe that China’s ASI was not done on an ad hoc basis, but with careful preparation. This is because, looking at China’s basic strategy, we can see that China has placed innovation at the center of its policy, and that, with intellectual property policy and standardization policy as the two wheels of its policy, there is an underlying trend toward establishing a dominant position in global governance, and that China is using this as leverage in its core technology fields to finalize a framework within the Chinese category. This is because it can be read as an attempt to use this as a lever to finalize a framework in the category of China in the field of core technology.

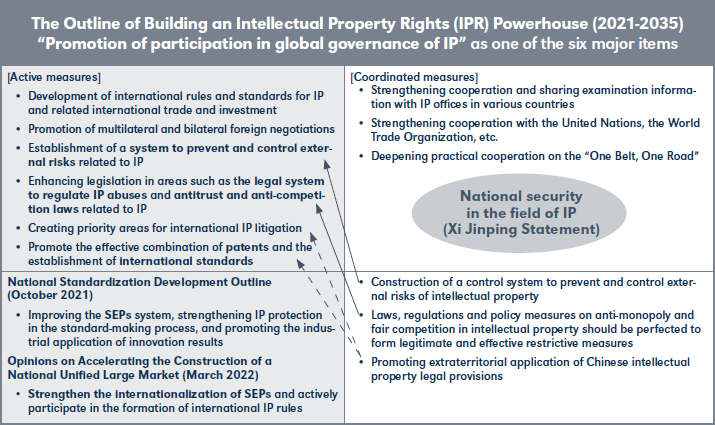

To understand this trend, we would first like to introduce “Xi Jinping’s Discourse at the 25th Collective Study of the Central Political Bureau” of November 2020. This is President Xi Jinping’s discourse on the topic of intellectual property protection at the Communist Party of China’s collective learning sessions, which are held several times a year. In this “Discourse,” one of the six main points of IP policy was presented: “national security in the field of intellectual property rights. In the context of this national security, legal regulations and policy measures on IPR antitrust and fair competition must be fully implemented, and legitimate and influential means of constraint must be formed,” and “China’s legal provisions on IPR must be promoted for extraterritorial application and cross-border judicial cooperation arrangements must be fully implemented.” This is a directive to position SEP disputes, the leading theme of antitrust in global IP disputes, as a national security issue and to ensure “extraterritorial application,” i.e., that global IP disputes can be settled in China in accordance with Chinese law. The “Jin-Su-Ling” can be seen as adopted as a concrete means of this.41

This direction can also be read from a series of important policy documents issued jointly by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council in recent years. China’s first long-term plan for intellectual property policy in 13 years, “The Outline of Building an Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Powerhouse (2021-2035)” (September 2021),42 the long- term plan for standardization policy known as “China Standard 2035,” the “National standardization development outline” (October 2021)43 and “Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of the National Unified Great Market” (March 2022) mentions active involvement in global governance and institutional improvements in SEP (see Table 2 on page 13).

To summarize, in China, the handling of SEP disputes is a national security issue, and in preparation for the critical milestone of 2035 for China, it is important to prevent foreign interference with judicial sovereignty44 and return the grand “Chinese dream” of establishing dominance in global governance by taking full advantage of its huge market power and promoting the extraterritorial application of Chinese laws can be seen as the background of the issuance of the “Jin-Su-Ling” as a legal weapon against foreign countries.

So far, all of the disputes related to the “Jin-Su-Ling” issued by China have involved Chinese companies in their capacity as implementers. However, a more bird’seye view of industry trends shows that Chinese companies are accelerating their aggressive R&D investment and involvement in standardization activities, and are strengthening their position as SEP rights holders, for example, by announcing that 40 percent of 5G-SEPs are already owned by Chinese companies.45 SEP license agreements are usually for three years (five years for the longest), but it is easy to imagine that Chinese companies, which have become powerful SEP right holders in the midst of portfolio expansion, will change their position toward FRAND rates to a more aggressive one. Chinese companies may, contrary to the past, utilize ASI in the future from the standpoint of a right holder, prevent the other party from seeking confirmation of the FRAND conditions in the other countries’ courts, and file patent infringement suits in China as a right holder to obtain a global FRAND rate decision favorable to their company. In this scenario, a Chinese company may seek a decision on the global FRAND rate in its favor from a Chinese court.

This is similar to the current Unwired Planet v. Huawei case. The point that ASI can be favorable to the right holder also undermines the Commission’s argument at the WTO that ASI is a restriction on patent enforcement or an obstacle to remedies for patent infringement. In addition, it is extremely difficult to establish strict and detailed common rules regarding the conditions for granting ASI on a uniform international basis in SEP disputes, which have a large case-by-case element due to differences in contractual negotiation situations. Therefore, unless countries, including Anglo- American law countries, abandon ASI in IP lawsuits, it will be difficult to settle ASI abuses through hard law, such as the WTO forum or treaties.

Given this background, it appears difficult to abandon the “Jin-Su-Ling” under external pressure in China, which is tackling SEPs as a high-level policy issue. However, it is very interesting to note that, although not well known outside of China, there is a strong cautious argument against ASI among Chinese domestic experts from the viewpoint that it infringes on the jurisdiction of other countries, and there are conflicting opinions within China. For example, “It is not appropriate to establish offensive ASI in China because ASI is suspected of infringing on the jurisdiction of other countries. There should be a defense system to prevent ASIs in other countries, for example, a safeguard system that would allow the party filing an ASI in another country to demand compensation for fines for ASIs in that country.”46 Also, “Where patent rights are independent of each country, it is an infringement of sovereignty for another country to restrict the exercise of rights with respect to the rights of a country with which no contract has been concluded. In addition, the right to file a lawsuit for the protection of rights is a fundamental constitutional right and an important part of human rights, and there is no clear constitutional basis for limiting this right under the ASI. While populist- backed ASI may create false innovation prosperity in the short term, in the long term it will ground the value goal of promoting innovation and creation through intellectual property and withdraw from international competition.”47 At a closed symposium in China, which the author was the only foreigner to attend in June 2022, there was a heated debate among Chinese judiciary officials.

While the discussion of reviewing the operation of ASI is progressing, the focus of attention is on the Anti-Monopoly Law. In China, there was a period in the early 2010s when the Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) was used to enforce the operation of SEPs by foreign companies (InterDigital, Qualcomm) and to settle SEP disputes. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which was in charge of Anti-Monopoly Law at the time, was active and successful in this regard, but the active application of Anti-Monopoly Law to SEPs has since become less common. However, the Anti-Monopoly Law has been revised for the first time since 2008 and will go into effect in August 2022.

In January 2019, the Antitrust Committee of the State Council formulated the “Guidelines on Antitrust in the Intellectual Property Rights Sector,”48 which specifically stipulates the anti-competitive and restrictive acts related to SEPs. In June 2022, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR, with the State Antitrust Bureau under its umbrella) released a draft revision of the “Regulation on Prohibition for Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights to Exclude or Restrict Competition” which added SEP-related provisions, for example, treating the exercise of injunction rights in violation of FRAND and good faith negotiation obligations as an abuse of dominant market position.49 The departments jointly announced the improvement of the SEP system and the promotion of the realization of a mechanism to link standards and IP in the action plan of the above-mentioned “National Standardization Development Guidelines.”50

In addition, in some antitrust litigation cases, not only SEP implementers but also SEP right holders have alleged that implementers with large market shares are abusing their dominant market positions to force unreasonably low license fee rates.51 (see Table 1 on page 11). Anti-Monopoly Law is a powerful defense mechanism, as is ASI, and as the presence of Chinese companies in the SEP market grows, the Chinese government is expected to support the global expansion of Chinese companies through various means, not limited to ASI operations.

5.1 Proposal for a Hybrid Solution Mechanism

ASI is by no means a legally illegitimate framework. However, it goes without saying that the exchange of ASIs and AASIs is a huge burden for both parties involved and, from the perspective of the international community as a whole, a waste of judicial costs in the public and private sectors. As the importance of “good faith” of both parties increases in SEP disputes, the situation that the filing of parallel lawsuits in another country is considered “bad faith” and is grounds for ASI in a lawsuit in one country, and the application for ASI itself is regarded as “bad faith” and is the basis for an injunction in the other country will lead to a divergence of judgments among the courts of each country, and will have a negative impact on the formation of a common understanding of how rights holders and implementers should behave.

Finally, we would like to consider possible ways to create a framework to deter such ASI abuse. Proposals have been made to establish a new independent third-party SEP dispute resolution body52 and to have governments first organize best practices from a soft law perspective.53 However, the authors believe that a hybrid solution mechanism should be sought instead of a court, etc. in violation of FRAND without conducting good faith negotiations.

There is likely no single-layer solution mechanism because the issues to be resolved in ASI are multi-layered as described in this paper. In other words, the issues to be resolved in ASI can be roughly summarized into two points: (1) whether an injunction should be granted based on a patent infringement suit and what damages should be awarded, and (2) how the global FRAND rate that could not be agreed between the parties should be determined. We believe that separate resolution mechanisms may be necessary to address these issues.

1. As for the “patent infringement lawsuits,” it seems reasonable to continue to follow this route in the future, considering that such lawsuits have been handled efficiently in the framework of traditional patent infringement lawsuits in the framework of domestic judicial proceedings by national courts under the patent laws of each country.

2. In addition, the global FRAND rate for a FRAND contract should be determined by a global framework, rather than by a court in a single country based on its individual judgment. In this case, SSOs, international arbitration organizations, etc. could be considered as a global framework instead of national courts. Each of these has its advantages and disadvantages, but what the authors expect is a hybrid combination of SSOs and arbitral institutions.54

In considering a solution mechanism, SSOs should not only formulate standards but also play a more advanced role. This is because standards are an important foundation for innovation creation for both right holders and implementers, and since the business and technological environment has changed significantly over the past decade, it is necessary to further update the existing IP policy. In the revised IP policy, both right holders and implementers should assume the FRAND obligation to negotiate in good faith when using standards, and it is desirable to incorporate rules on ASI in the policy.

Arbitration institutions are strong candidates as third-party institutions for setting global FRAND rates.55,56 Experts (technology, economists, etc.) can participate in the arbitration process, making it suitable for flexible agreement formation. As for enforcement, the New York Convention (Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards)57 exists to ensure enforceability. Therefore, it is conceivable that if the parties cannot reach an agreement on the global FRAND rate, the SSO’s IP policy should stipulate that the matter be resolved through international arbitration and leave it to that mechanism. However, the disadvantage of arbitration is its openness. In this regard, in view of the public interest of the global FRAND rate, the agreement on the rate should, in principle, be open to the public, and this should be clearly stated in the revised IP Policy. On the other hand, the resolution of infringement, injunction, and validity of rights through arbitration is not realistic in terms of cost due to the large number of SEPs and the number of issues. Here, the amount of damages determined in an infringement lawsuit should not affect the conclusion of future license agreements, and if a judgment is rendered that conflicts with the amount of damages, an ASI may be issued by the court of the place of arbitration to give priority to the arbitral award and limit the enforcement of the judgment.

5.2 Avoid Making This a Nation-to-Nation Political Issue

Finally, it is important to avoid making the conflict over SEPs into a state versus state construct. The Chinese government’s recent policy on SEPs is closely related to IP security and global governance, as noted above, and is beginning to be treated as an issue pertaining to the expansion of China’s “Hua-yu-quan(话语权).”58 The EU’s WTO complaint can be taken as an indication that this issue is becoming an international political issue. However, SEPs are a private-public (business-to-business) issue, not a state-to-state issue. The situation where the number of SEP holders in China is increasing means that there is a conflict-of-interest structure among companies even within China. However, if the Chinese companies that are rights holders and implementers join hands with each other and their interests are separated along with their supply chains, it will become increasingly difficult to solve problems on a global scale. We should consider bringing Chinese companies with various interests into the international cooperation framework, establish a basic stance that ASI should be used modestly in relation to respect for “integrity” as a rule between the parties, and guide them in a direction that will contribute to global problem solving and the development of innovation.

Since the Samsung v. Ericsson decision in the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court on December 25, 2020, no ASI has been issued. Indeed, there has been a severe confrontation taken by the U.S. and Europe over the ASI. As already mentioned, the European Commission submitted a petition for investigation to the WTO (February 18, 2022), a German court ruled that AASI was issued as a countermeasure to ASI, and a number of rulings have been issued, such as one recognizing the act of filing an ASI as an act of “unwillingness” (by the implementer). There have also been a number of court decisions recognizing the act of filing an ASI as an act of unwillingness. Meanwhile, in the U.S., on March 8, 2022, a bipartisan group of U.S. Senators introduced the “Defending American Courts Act,” which would penalize Chinese ASI as an obstruction of law enforcement in U.S. courts. At first glance, it would appear that both Chinese courts and the Chinese companies that file ASIs have become more cautious about the use of ASIs.

However, if we look at the ASI (“Jin-Su-Ling”) from the perspective of 2022, when considering it in connection with the revised Anti-Monopoly Law and related provisions that came into effect on August 1, 2022, the ASI (“Jin-Su-Ling”) may have ended its role as a preliminary battle and passed the baton to the revised Antitrust Act. Professor Mark Cohen (Berkeley Center for Law and Technology), an expert on the policy situation in China, also published an article describing the transition from the ASI to the AML (Anti-Monopoly Law).59

For the authors, who have been following China’s trends for many years, the ASI (“Jin-Su-Ling”) is accompanied by a claim of global FRAND rate jurisdiction, and for China, it is a “China’s dream” to create global rules from a party that follows global rules. It looks like a party taking the first step toward realization. This is clearly reflected in Xi’s active involvement in the global governance of intellectual property, which General Secretary Xi himself refers to, including the “The Outline of Building an Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Powerhouse (2021-2035).” It will be necessary to consider whether we will come closer to realizing that dream by adding the revised Antimonopoly Act as the next weapon, including how to deal with it.

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=4337698.

Table 1. Representative SEP Related Lawsuits in Recent Years (China/Jurisdiction-Related) |

||||||

| Nature | Practitioner | Right holder | Chinese lawsuit | Major parallel lawsuits | Remarks/ Whether or not ASI decision is disclosed | |

| UK ASI Global Rate | Huawei | Unwired Planet | July 2017 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Violation of the Antitrust Act Oct. 2017 Withdrawn | March 2014 [UK High Court] Infringement lawsuit April 2017 [UK High Court] Infringement found (Global rate jurisdiction accepted) October 2017 UP applied for ASI October 2018 [UK Court of Appeal] Appeal dismissed (first instance upheld) August 26, 2020 [UK Supreme Court] Appeal dismissed | ||

| Huawei/ ZTE | Conversant | Refer to the following (In 2018, ZTE limited the Shenzhen Intermediate Lawsuit to confirming FRAND conditions in China) | 2017 [UK High Court] Infringement lawsuit April 2018 [UK High Court] Jurisdiction objection dismissed (Global rate jurisdiction accepted) July 2018 Conversant applied for ASI January 2019 [UK Court of Appeal] Appeal diSmissed (first instance upheld) August 26 , 2020 [UK Supreme Court] Appeal dismissed * Merge with the UP case | |||

| US ASI | Samsung | Huawei | 2016 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Infringement lawsuit* cross license FRAND violation 2018 Infringement Findings 2018 [Guangdong High] Infringement Certification | 2016 [SF Northern District Court] Infringement lawsuit In April 2018, Samsung applied for ASI → ASI (prohibition of execution of the Shenzhen ruling) | settlement | |

| ASI | Huawei | Conversant | January 2018 [Nanjing Intermediate] Non-infringement confirmation/Rate confirmation litigation September 2019 [Nanjing Intermediate] Partially invalid, partly infringing (top-down rate) August 27, 2020 Huawei applied for ASI → [Supreme Court] ASI (prohibition of application for execution of German judgment) | April 2018 [Düsseldorf District Court] Infringement lawsuit August 27 , 2020 [Düsseldorf District Court] Finding of infringement *See above for UK litigation | 2020 _ 10 Supreme Court Cases 10 major IP proposals settlement |

Published on the official website |

| ASI | ZTE | Conversant | January 2018 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Lawsuit for rate confirmation and FRAND condition confirmation January 2019 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Jurisdiction objection dismissed August 21, 2020 [Supreme Court] Dismissal of objection to jurisdiction August 28 , 2020 ZTE applied for ASI → [Shenzhen Intermediate] ASI(prohibition of application for enforcement of German judgment) | April 2018 [Düsseldorf District Court] Infringement lawsuit August 27 , 2020 [Düsseldorf District Court] Finding of infringement *See above for UK litigation | November 2020 _ _ dismissal of the lawsuit, settlement |

Published on an unofficial site |

| ASI Global rate | OPPO | Sharp | March 2020 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Global Rate Confirmation Lawsuit and ASI October 2020 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Jurisdiction objection dismissed and ASI (Worldwide) August 2021 [Supreme Court] Dismissal of objection to jurisdiction (affirmation of global rate jurisdiction) | January/March 2020 [Tokyo District Court] Infringement lawsuit March 2020 [Munich/Mannheim District] Infringement lawsuit April 2020 [Taiwan] Infringement lawsuit October 2020 [Munich] AASI/AAAASI Judgment | 2020 _ 10 major IP proposals October 2021 _ _ settlement |

Published on an unofficial site |

| ASI Global Rate | Xiaomi | InterDigital | June 2020 [Wuhan Intermediate] Global Rate Confirmation August 2020 Xiaomi applied for ASI December 2020 [Wuhan Intermediate] ASI (Worldwide) | July 2020 [Delhi High Court] Infringement lawsuit September 2020 IDC applied for AASI October 2020 [Delhi High Court] AASI Judgment * Others; Germany | August 2021 _ _ settlement |

Published on an unofficial site |

| ASI Global Rate | Samsung | Ericsson | December 7, 2020 [Wuhan Intermediate] Global Rate Confirmation Lawsuit December 25, 2020 [Wuhan Intermediate] ASI (Worldwide) | December 11, 2020 [East District Court of Texas] Infringement lawsuit December 25 , 2020 Ericsson applied for AASI January 17, 2021 [East District Court of Texas] AASI Judgment | May 2021 _ _ settlement |

Published on an unofficial site |

| ASI (Denied) | Lenovo | Nokia | November 2020 [Shenzhen Intermediate] China Rate Verification Lawsuit & ASI January 27 , 2021 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Lenovo‘s application for an ASI dismissed | September 2019 [North Carolina Eastern District Court] Infringement lawsuit July 2020 [US ITC] Injunction application September 2020 [Munich District Court] Recognition of infringement *Others; Brazil, India, etc. | April 2021 _ _ settlement |

Published on the official website |

| Global Rate | OPPO | Nokia | 2021 [Chongqing Intermediate] Global Rate Verification Litigation September 2022 [Supreme Court] affirmation of global rate jurisdiction | July 2022 [Mannheim District Court] Infringement *Others; UK, France, Spain, India, Indonesia, Russia, etc. | ||

| Global Rate | Tinno / WIko | ZTE | September 2021 [Shenzhen Intermediate] Global Rate Confirmation Lawsuit | The first case in China where a right holder of a Chinese company requested a judgment on a global rate. Tinno is an ODM manufacturer. | ||

| Antitrust law foreign jurisdiction | OPPO | Sisvel | Sept., Dec. 2019 [Guangzhou IP] Rate confirmation, antitrust lawsuit July 2020 [Guangzhou IP] Jurisdiction objection dismissed Dec. 2020 [Supreme Court] Jurisdiction objection dismissed | 2019 [UK, Netherlands, Italy] Infringement lawsuit | 2020 _ 10 major antitrust cases Settlement in July 2021 (mediation) |

|

| Antitrust law | Apple | Western Electric | April 2016 [Shaanxi High] Infringement Lawsuit (Plaintiff Western Electric) Oct. and Dec. 2016 [Beijing IP] Rate Confirmation and Antitrust Violation (Plaintiff Apple) July 2018 [Beijing IP] Antitrust violation counterclaim (plaintiff Western Electric) → Not accepting July 2022 [Beijing High] Support of the first instance counterclaim (not accepting Western Electric’s application | March 2018 [Hong Kong Arbitration] Arbitration for rate determination filed December 2019 [Hong Kong Arbitration] Arbitration Tribunal Has Jurisdiction →Continued refusal on the grounds that the arbitrator designated by Western Electric was unfairly excluded | ||