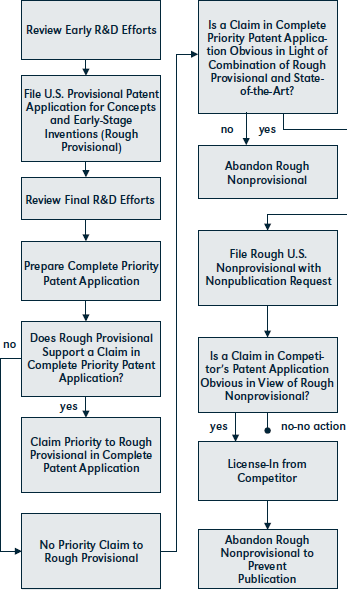

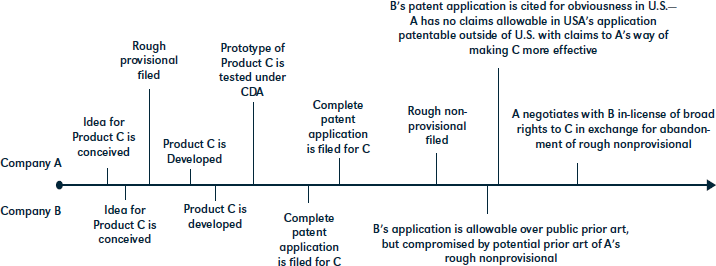

If during U.S. examination of one's complete priority patent application, or as otherwise revealed by a patent search, a competitor's patent application having an earlier filing date is discovered, the loss of patent scope in the U.S. due to the earlier-filed application will likely be more severe than in other countries. If the rough provisional pre-dates the filing of the earlier-filed application—meaning that work on the invention by one's inventor's had started before the competitor was able to file a patent application for the invention—then the consequences of being second-to-file need not be so severe in the U.S.

The analysis that concluded that the rough provisional should be filed as a rough nonprovisional can be repeated for the competitor's patent application. The claims in the competitor's application can be studied to determine if they are vulnerable to an obviousness rejection on the basis of the rough provisional's teachings and the whole prior art. If this is the case, then the rough nonprovisional has value. If it is unpublished, then the rough nonprovisional is a negotiation tool. If it was published, then it can be cited against the competitor's patent application.15

The applicant of the unpublished rough nonprovisional has control over its publication,16 and its ability to be cited as prior art against the competitor's patent application. If the rough nonprovisional is never published, it never becomes prior art and never impacts on the validity of the competitor's future patent.17

Disclosure of the unpublished rough nonprovisional to the competitor does not create any negative consequence, as for example a duty to disclose it as prior art to the USPTO, since it is not prior art yet. The competitor can take the required time to consider the potential prior art effect of the rough nonprovisional, and the value of its never becoming prior art.

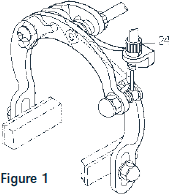

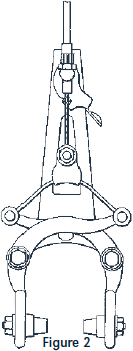

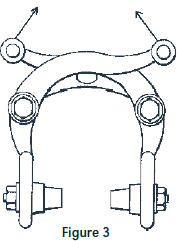

In the example of the bicycle brake, let's presume the inventor of the side-pull brake was first to file a complete application and the inventor of the centerpull brake was first to conceive the brake. Let's also presume the inventor of the center-pull brake files a rough provisional before the side-pull brake patent application is filed, and then files a complete patent application after the side-pull application. In this scenario, the inventor of the center-pull brake will enjoy certain rights outside the USA, but could see the claims granted outside the USA be rejected for obviousness in light of the side-pull application in the USA. However, the rough nonprovisional has the power to invalidate the side-pull patent application in the USA if it were published. The rough concept of the rim brake described in the rough provisional could, in combination with other prior art, render obvious the invention described and claimed in the side-pull brake application. Control over this publication is the bargaining chip that the inventor of the center-pull brake has over the inventor of the side-pull brake.

While no one is ever pleased to offer the competition a license to one's patent, avoiding the prior art effect of the rough nonprovisional, and possibly the invalidity of one's broad patent claims, is a strong incentive to license. When two applicants are close in filing patent applications for the same or similar inventions, the second-to-file applicant regularly obtains partial patent rights in First-to-File countries (outside the U.S.), and the competitor might already have accepted that the second-to-file enjoys certain patent rights for the invention. The objective of a license can be to enjoy the same effective rights as in other countries, or to enjoy a full license to competitor's patent. The ability to negotiate will depend on the potential prior art effect of the rough nonprovisional. If the potential prior art effect of the rough nonprovisional is the likely unpatentability of all meaningfully broad claims, a royalty-free, transferable license might be warranted.

There is a good opportunity in the above-described scenario to negotiate a license or settlement amount for the abandonment of the rough nonprovisional. In the case that a competitor was the first-to-file a complete patent application for an invention, the goal of the license would be to give a second-to-file applicant (who filed an earlier rough provisional, followed up by an unpublished, rough nonprovisional) access to rights equal to, or better than, those offered in other jurisdictions. Licensing can become an integral part of patent procurement in the AIA framework!

- http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/paris/trtdocs_wo020.html.

- http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/t_agm0_e.htm, Article 2.

- This follows from Paris Convention Article 4F that permits an application to claim multiple priorities or to claim priority of an earlier patent application while describing further elements not in the earlier application. Priority is thus based on elements of the application, and claims to different elements can have different priorities.

- www.wipo.int/pct/en/texts/pdf/ispe.pdf.

- This also follows from Paris Convention Article 4F that introduces the notion that priority relates to the "elements… included in the application whose priority is claimed" as well as Article 4H (see below note) that requires specific disclosure of the elements claimed.

- Paris Convention Article 4H reads, "Priority may not be refused on the ground that certain elements of the invention for which priority is claimed do not appear among the claims formulated in the application in the country of origin, provided that the application documents as a whole specifically disclose such elements."

- The exclusion of earlier-filed patent applications from being cited for obviousness is defined by Article 56 EPC that states, "If the state of the art also includes documents within the meaning of Article 54, paragraph 3 (i.e. earlier-filed patent applications), these documents shall not be considered in deciding whether there has been an inventive step." In Canada, third party earlierfiled patent applications are novelty-destroying under Section 28.2(c),(d) and the definition of information that may be relied on for considering obviousness under Section 28.3 excludes the prior art of Section 28.2(c),(d).

- 35USC§102(a) includes earlier-filed patent applications from another inventor as prior art. 35USC§102(c) defines "another inventor" to extend to other applicants. 35USC§103 requires a claimed invention to be nonobvious in view of the prior art as defined in 35USC§102 without exception.

- Under 35USC§102(e) prior to AIA, an earlier-filed patent application was prior art if it was filed before the inventor made his invention. 37CFR1.131 allowed for an affidavit of prior invention to be submitted to dismiss as prior art a 35USC§102(e) reference.

- MPEP 2121.01 cites Beckman Instruments v. LKB Produkter AB, 892 F.2d 1547, 1551, 13 USPQ2d 1301, 1304 (Fed. Cir. 1989) as stating "Even if a reference discloses an inoperative device, it is prior art for all that it teaches." And further cites Symbol Techs. Inc. v. Opticon Inc., 935 F.2d 1569, 1578, 19 USPQ2d 1241, 1247 (Fed. Cir. 1991) as stating "A non-enabling reference may qualify as prior art for the purpose of determining obviousness under 35 U.S.C. 103."

- In this simple mechanical example, it might have been fully possible to have identified and specified the cable mount and its operation, such that a full priority would have been established. This would be beneficial to the applicant to obtain the earliest priority date. The author assumes that the elements omitted from the rough provisional were not readily available to the applicant, and would have required the effort of R&D over a number of weeks or months.

- 35USC§102(b)

- 35USC§122(b)(2)(B)(i)

- 35USC§122(b)(2)(B)(iii) states "An applicant who has made a request under clause (i) but who subsequently files, in a foreign country or under a multilateral international agreement specified in clause (i), an application directed to the invention disclosed in the application filed in the Patent and Trademark Office, shall notify the Director of such filing not later than 45 days after the date of the filing of such foreign or international application. A failure of the applicant to provide such notice within the prescribed period shall result in the application being regarded as abandoned, unless it is shown to the satisfaction of the Director that the delay in submitting the notice was unintentional."

- 35USC§122(e) allows for a published patent application to be submitted by a third party if it is done within 6 months from publication or prior to a first office action on the merits. A third party can provide prior art directly to the applicant or her patent attorney with the expectation that it will be brought to the attention of the USPTO under the duty to disclose of 37CFR1.56.

- 35USC§122(b)(2)(B)(iv) allows for the applicant to rescind the nonpublication request.

- Publication under 35USC§122 is a requirement for an earlier-filed application to be prior art under 35USC§102(a)(2).