Mariella Massaro

Partner

Berggren Group

Helsinki, Finland

Mariella Massaro

Partner

Berggren Group

Helsinki, Finland Suvi Julin

Partner

Berggren Group

Oulu, Finland

Suvi Julin

Partner

Berggren Group

Oulu, Finland Jennifer Burdman

Managing Director

Sauvegarder Investment Management

Boston, MA, U.S.A.

Jennifer Burdman

Managing Director

Sauvegarder Investment Management

Boston, MA, U.S.A. Robert Alderson

Partner

Berggren Group

Helsinki, Finland

Robert Alderson

Partner

Berggren Group

Helsinki, FinlandWe are now well past the one-year anniversary of the new European patent system which notably includes a new type of patent, a European patent with unitary effect, also known as a Unitary Patent, as well as a new court system, the Unified Patent Court (UPC). The new European system provides opportunities for patent prosecution strategies which can be agreed upon in advance and which are covered in the first section below. In conjunction with those prosecution strategies, patent owners should be mindful of the nuances in how the Unified Patent Court is interpreting the right to enforce those Unitary Patents. Recent interim orders and decisions from the Unified Patent Court provide guidance on how various stakeholders can control risk and uncertainty through the use of properly drafted agreements. This article addresses key aspects of license and joint ownership agreements relating to patent prosecution and litigation, including standing to sue of licensees as well as joint owners. The article also includes brief comparative information on United States law relating to standing to sue of licensees and joint owners, important for patentees seeking to engage with third parties in both jurisdictions.

Since 1 June 2023, when the UPC started to operate, and for the duration of what is referred to as the “transitional period” stipulated by Art. 83(1) UPCA, owners of European patent applications have the option of either validating the patent in the countries of interest participating in the European Patent Convention or to request unitary effect in the countries participating in the UPC system. Therefore, the transitional regime offers a number of possibilities on filing and prosecution strategies that should be considered in view of managing patent portfolios, building strong licensable patent portfolios, and drafting licensing agreements with the intended enforcement rights.1

Filing and Prosecution Strategies Utilizing Divisional Applications

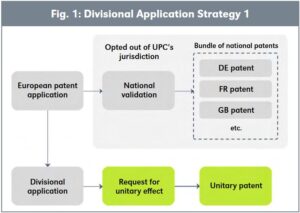

From the patentee’s point of view, the transitional regime offers a relatively long window of time during which different filing and prosecution strategies are available. Certain strategies extend beyond the transitional regime as well. One of the potentially useful strategies, which enables risk balancing in view of the Unitary Patent System, is to use a divisional application strategy shown in Figure 1.

Based on divisional applicatio strategy 1, the applicant can obtain a “parent” European patent application with a wider scope of protection and the granted European patent will be validated nationally in the selected EPC member states. The “parent” European patent will be opted out of the jurisdiction of the UPC. The divisional application(s) are strategically filed with claims targeting a narrower scope of protection to avoid a double patenting objection and when granted, the unitary effect will be requested for the divisional(s). Divisional application strategy 1 enables building a potentially stronger patent portfolio where the risk of central attack against the “parent” European patent can be effectively mitigated (because it was opted out of UPC jurisdiction) and the UPC can still be utilized, if needed, with the divisional patent(s). As discussed in more detail below, this may be beneficial from a licensing point of view but requires well-defined license management clauses in licensing agreements, and in the case of joint ownership, attention must be paid to managing decision-making contractually between joint owners. This strategy also may be beneficial, for example, if the wider scope of protection provided by the “parent” European patent may have some weaknesses (from a patentability standpoint) in comparison to the narrower divisional(s).

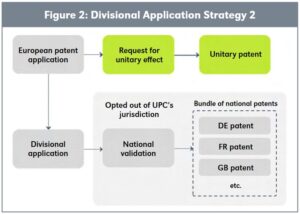

Divisional application strategy 2 as described in Figure 2 is, in practice, the inverse of the strategy presented in Figure 1. In this case, the “parent” European patent is a Unitary Patent and the divisional patent(s) are nationally validated in EPC member states. The divisional patent(s) have a narrower scope of protection to avoid any double patenting objection and are opted out of the UPC’s jurisdiction.

This strategy may be useful in various situations if the risk of central attack against the “parent” European patent can be accepted and the divisional(s) provide a preferable scope of protection in certain countries, for example. Similar to divisional application strategy 1, this option also enables the creation of a potentially stronger patent portfolio and requires well-defined license management clauses in license and joint-ownership agreements. It may also be beneficial, for example, if the wider scope of protection provided by the “parent” European patent may have some weaknesses (from a patentability standpoint) in comparison to the narrower divisional(s) and certain countries even with a narrower scope of protection are more important for the patentee than others.

Filing and Prosecution Strategies Utilizing National Applications

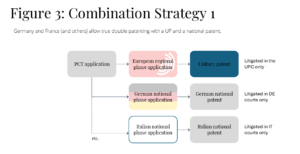

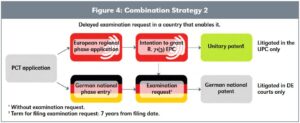

Certain EPC and UPC member states such as Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Finland allow literal double patenting. While the opt out-based divisional strategies 1 and 2 described above remain useful for the duration of the transitional regime, national applications based on combination strategies remain applicable after the transitional regime as well. Figures 3 and 4 provide examples of combination strategies where a European patent application/Unitary Patent is combined with national patent applications/patents by utilising a PCT application and entering the regional phase before the European Patent Office and selected national offices in parallel within the time limits of the PCT (where such route is not blocked).

Generally, combination strategies utilising national patent application filings may be beneficial for building stronger portfolios and balancing risks but require particular attention to relevant contract provisions in license and joint ownership agreements, as discussed above. Utilising national patents in combination with Unitary Patents is especially beneficial if there are certain countries that are particularly commercially important for the patentee and where double patenting is permitted. Also, if variation in the scope of protection possibly resulting from national patents can be accepted, national patents in combination with a Unitary Patent can be an alternative that may increase the value of licensable patent portfolios. Of particular note, in Germany, delaying examination requests up to seven years from the date of filing is also possible and would allow optimization of prosecution and scope of protection in view of the claims already granted in the European patent application (Fig. 4).2

During the transitional regime as stipulated by Art. 83(1) UPCA, an action for infringement or for revocation of a European patent may still be brought before national courts in case of European patents validated traditionally in UPC member states. Further, Art. 83(3) and 83(4) UPCA establish so-called opt-out and opt-in procedures together with Rule 5 of Rules of Procedure (“RoP”).

Unless an action has already been brought before the UPC, a proprietor of or an applicant for a European patent granted or applied for prior to the end of the transitional period shall have the possibility to opt out from the exclusive competence of the UPC by notifying the Registry by the latest one month before expiry of the transitional period (Art. 83(3) UPCA). Rule 5 of the Rules of Procedure for the UPC stipulates that the proprietor of a European patent (including a European patent that has expired) or the applicant for a published application for a European patent who wishes to opt out that patent or application from the exclusive competence of the UPC can lodge an application to opt out with the Registry.

Art. 83(4) UPCA further stipulates that unless an action has already been brought before a national court (of a UPC member state), proprietors of or applicants for European patents who have made use of the opt-out procedure in accordance with Art. 83(3) UPCA shall be entitled to withdraw the opt out at any moment by notifying the Registry accordingly. Opting out and withdrawing an opt out (“opting back in”) can only be done once pursuant to Rule 5(10) RoP. Further, where an application for a European patent that has been opted out proceeds to grant as a European patent with unitary effect, the opt out shall be deemed to have been withdrawn. At the end of the transitional period, the European patents that have opted out will remain opted out, and thus they will be subject to the jurisdiction of the respective national courts.

The UPC has already issued orders related to the validity of opt outs and withdrawals of opt outs and, although not specifically related to joint ownership, certain aspects should be considered. In the matter Mala Technologies v Nokia Technology (UPC_CFI_484/2023) the Paris Central Division as a first instance held that there is no general principle within the UPCA that precludes the UPC from asserting jurisdiction in revocation proceedings merely because other proceedings relating to the same patent are pending before other courts. The Court indicated that the interests of claimants filing revocation lawsuits before and after the entry into force of the UPCA are distinct. The Court stated that a party which filed a lawsuit in a national court before the entry into force of the UPCA should not be barred from filing a lawsuit before the UPC because, at the time of filing the national lawsuit, the UPC was not yet operational. The Court reasoned that at that time a claimant could not make a choice between the UPC and a national court. In contrast, a claimant which files a lawsuit during the transitional period can make such a choice.3

It should be noted that a previous decision by the Helsinki Local Division in the matter AIM Sport Vision v Supponor (UPC_CFI_214/2023) as a first instance court determined that withdrawal of an opt out was ineffective due to the national infringement and invalidation proceedings before the German courts and, as a result, the UPC lacked competence. The Court considered that reading of Art. 83(4) UPCA and Rule 5.8 RoP causes a withdrawal of an opt out to be irrespective of whether the national action is pending or it has been concluded, and in this case the German national action was still pending on the date of withdrawal of the opt out.4

Presumably, the different approach taken by these two courts will be resolved by subsequent UPC jurisprudence.

This section will provide some basic information regarding the legal principles governing patent licensing and the ability to bring infringement actions in the United States and Europe before reviewing recent cases of the Unified Patent Court relating to similar issues.

Standing to Sue of the Licensor and Licensee under United States Law

In order to sue for patent infringement in the U.S., the plaintiff must meet jurisdictional requirements to show that it has been injured by the defendant’s alleged infringement (referred to as standing under Article III of the U.S. Constitution) and that it has the right to exclude the use of the technology as the “patentee” (35 U.S.C. § 281).5 The U.S. Patent Act defines a “patentee” here as the party to whom the patent was issued and the successors in title to the patentee, but it does not include mere licensees. Nevertheless, it is recognized that “[a] patent owner may transfer all substantial rights in the patents-in-suit, in which case the transfer is tantamount to an assignment of those patents to the exclusive licensee,” who may then maintain an infringement suit in its own name.6 In many cases, the analysis of “injury by defendant” has been collapsed into the discussion of whether the plaintiff has the right to exclude the use of the technology by that defendant as an exclusive licensee/“patentee” under § 281.

In order for an “exclusive licensee” to be able to sue for infringement (without having the patent owner licensor joined in the lawsuit), the licensee must have “all substantial rights” including the “exclusionary right” to sue for alleged infringement. If a license does not explicitly transfer the right to sue to the licensee, the licensee may not have the right to sue on its own. This necessarily impacts how patent owners structure and phrase their license agreements that include the U.S. territory, particularly where, as discussed above, patent owners may choose to reserve key rights to their licensed patents for strategic reasons.

While the U.S. courts have not established a brightline rule for language that must be included in the contract to provide an exclusive licensee with sufficient rights to bring an infringement action (without including the licensor in the suit), they have provided the following criteria to be examined under the “totality” of the license agreement. That list of criteria includes: (1) the scope of the licensee’s right to sublicense, (2) the nature of license provisions regarding the reversion of rights to the licensor following breaches of the license agreement, (3) the right of the licensor to receive a portion of the recovery in infringement suits brought by the licensee, (4) the duration of the license rights granted to the licensee, (5) the ability of the licensor to supervise and control the licensee’s activities, (6) the obligation of the licensor to continue paying patent maintenance fees, and (7) the nature of any limits on the licensee’s right to assign its interests in the patent. Among these factors that are to be considered, the exclusive right to make, use, and sell, as well as the nature and scope of the patentee’s retained right to sue accused infringers are the most important considerations in determining whether a license agreement transfers sufficient rights to render the licensee the owner of the patent and confer standing to sue in U.S. federal court.7

Standing to Sue of the Licensor/Patent Owner before the Unified Patent Court

The licensor’s entitlement, as the patent owner, to file suit and to join actions started by its licensee is expressly provided for by Article 47 (Parties) of the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA):

1. The patent proprietor shall be entitled to bring actions before the Court.

(…)

4. In actions brought by a license holder, the patent proprietor shall be entitled to join the action before the Court.

In the now well-known case 10X Genomics and Harvard v Nanostring, which resulted in the first preliminary injunction granted based on a Unitary Patent, the Munich Local Division addressed the issue “whether the formal legal position according to the entry in the register is sufficient for entitlement under Article 47(1) UPCA, or whether the substantive entitlement is ultimately decisive,” affirming that this question can remain open for decision in the proceedings on the merits, while the formal entitlement was deemed sufficient in the urgent proceedings (10X Genomics and Fellows of Harvard College v NanoString Technologies).8

This approach was upheld in the appeal phase, where the UPC confirmed that

“The concerns raised in the Appeal against the entitlement of Applicants 2 [Harvard] to file the application are not justified. Due to their corresponding entry in the Register for Unitary Patent Protection, Applicants 2 are to be treated as the proprietor of the patent at issue, in accordance with R. 8.4 RoP. As such, they are entitled to apply for provisional measures in accordance with Art. 47(1) UPCA.” 9

In this regard, the Court of Appeal referred to Rule 8.4., which provides:

For the purposes of proceedings under these Rules in relation to the proprietor of a European patent with unitary effect, the person shown in the Register for Unitary Patent protection [Regulation (EU) No 1257/2012, Article 2(e)] as the proprietor shall be treated as such.

A subsequent decision of the Düsseldorf Local Division in the 10X Genomics v Curio Bioscience case clarified that

“If in the case of a European patent a person is registered as the patent proprietor in the respective national register, there is a rebuttable presumption that the person recorded in the respective national register is entitled to be registered (R. 8.5(c) RoP). The result of such a legal presumption is to reverse the burden of explanation and proof with regard to the presumed fact. If the Applicant can refer to his listing in the registers relevant to the respective dispute, it is up to the Defendant’s side to set out and, if necessary, prove that the Applicant is not entitled to be registered.” 10

Standing to Sue of the Licensee before the Unified Patent Court

Article 47 UPCA also recognizes the entitlement of the licensee to file suit, but makes a distinction between the position of an exclusive and a non-exclusive licensee:

2. Unless the licensing agreement provides otherwise, the holder of an exclusive license in respect of a patent shall be entitled to bring actions before the Court under the same circumstances as the patent proprietor, provided that the patent proprietor is given prior notice.

3. The holder of a non-exclusive license shall not be entitled to bring actions before the Court, unless the patent proprietor is given prior notice and in so far as expressly permitted by the license agreement.

Notwithstanding the default position of Article 47 UPCA, it is important to understand that the licensor and the licensee are free to negotiate additional or different contractual requirements. In particular, the license agreement can include an obligation for the exclusive licensee to request the licensor’s consent before bringing an infringement action at the UPC.

In the dispute involving 10X Genomics and Harvard University v Nanostring before the Munich Local Division, referenced above, the defendant Nanostring contested the exclusivity of 10X Genomics’ license, and thus its right to bring actions before the Court. In particular, the defendant pointed out that Harvard’s research that resulted in the patent at issue was financed by the NIH and that the funding was subject to certain contractual obligations under the Bayh-Dole Act, including the obligation to grant non-exclusive licenses to third parties to the results of the funded activities. However, notwithstanding this obligation, Harvard University granted two exclusive licenses to 10X Genomics covering different territories.

The Munich Local Division decided that

“In the event that Claimant 2) [Harvard University] has made a commitment to the NIH to grant non-exclusive patent licences with respect to the patent at issue, the Local Division cannot be convinced with sufficient certainty in the summary proceedings that it was possible to grant an exclusive licence contrary to this commitment; this question is therefore reserved for a detailed examination of the relevant US law in the proceeding on the merits in the event that it is relevant for a decision.”

However, this issue did not have any practical impact on the proceedingss, because, as the Munich Court pointed out

“According to Article 47(3) UPCA, the holder of a non-exclusive licence is also entitled to file a request if the patent proprietor has been informed of the seizing of the court by said holder and the licence agreement expressly allows the request to the court. The court is convinced that both are the case here: Claimant 2) [Harvard University] was informed of the seizing of the court by Claimant 1) [10X Genomics]; the request was filed together with Claimant 1). According to the submission in the written statement of 11 August 2023, both Claimants also agree that there is at least a non-exclusive licence agreement between them concerning the patent at issue, which allows Claimant 1) to bring the matter before the court in the sense of the asserted request. It is also neither apparent nor submitted by the Defendant side that any infringements of NIH funding conditions resulting from the grant of an exclusive licence prevent a later agreement on a simple licence.”

These principles were upheld by the Court of Appeal and are currently under the consideration of the judges in the proceedings of the merit.

Counterclaim for Revocation by the Defendant in UPC Infringement Actions brought by the Licensee

In the framework of a UPC litigation including a counterclaim for revocation, Article 47.5 of the UPC Agreement provides the following:

“The validity of a patent cannot be contested in an action for infringement brought by the holder of a licence where the patent proprietor does not take part in the proceedings. The party in an action for infringement wanting to contest the validity of a patent shall have to bring actions against the patent proprietor.”

This provision along with Rule 25.2 of the RoP appears to force the defendant to bring a separate revocation action before the Central Division, unless the patent owner joins the original infringement proceedings brought by the licensee.

If this interpretation is confirmed by UPC case law, it would be preferable to allow some flexibility in license agreements so that the licensor and licensee are not bound to bring infringement actions jointly but are free to evaluate the litigation strategy based on the concrete circumstances of the case.

First FRAND Issues at the Unified Patent Court

In 2023, Panasonic filed a number of SEP infringement actions against Xiaomi, OPPO and other parties before the Mannheim LD. Although these proceedings have not yet reached a decision on the merits, the UPC has already issued several orders concerning the submission of evidence which gives some indication of how it will evaluate these cases.

The Mannheim LD followed the principles set forth by FRAND case law of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), in particular the leading case Huawei v ZTE, which defined the “negotiation program that outlines the steps that the parties must take on the path to result-oriented negotiations of a fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory license agreement.” 11

Referring to the CJEU’s ruling, the Court noted that the patent owner is required, under EU law, to “submit a specific written license offer on FRAND terms and, in particular, to specify the license fee and the method of calculating it (ECJ Huawei v. ZTE, ECLI: EU:C: 2015:817 para. 63).”

With respect to the latter requirement, the UPC also clarified that

“For the explanation of the manner in which the license fee is calculated, as required by the ECJ, it is not sufficient to simply state the mathematical factors on which the calculation is based. Rather, the ratio on which the ECJ is based must be made transparent as to why the SEP holder believes that the offer it is making to the alleged infringer complies with FRAND conditions. The necessary justification can be provided, for example, by reference to a licensing practice already established in the market in the form of a standard licensing program. If no such program exists, specific individual license agreements can be used as a benchmark if it is explained why the SEP holder believes that they can use these as a suitable reference point in comparison with the alleged infringer.” 12

Another issue addressed by the UPC, in relation to the submission of SEP license agreements by Panasonic as the SEP holder, was how to reconcile the requirements set forth by EU antitrust law with confidentiality provisions typically drafted under U.S. law, which subject the disclosure of the license content only upon the consent of the contractual party, compelling legal reasons or a court order. In this respect, the Court noted that “as a result, the corresponding clauses only incompletely take into account the mutual transparency obligations of the parties arising from EU antitrust law.”

On a separate note, the Court also pointed out the conflict between U.S. style confidentiality provisions and UPC procedural law, in particular

“when disclosure is only permitted to the respective party representatives, but not to a natural person of the party concerned (attorneys’ eyes only confidentiality club)” and thus concluded that “in this respect, the party’s obligation under EU antitrust law to behave transparently when negotiating a FRAND license and enforcing patent rights from an SEP outweighs the conflicting clause and its application by the contracting party concerned. This is because anyone who includes confidentiality clauses in a contract that also concerns standard-essential patents that are enforceable in the European Union, which are in conflict with the EU antitrust law requirements for transparency, cannot generally refuse consent on sufficiently worthy legal grounds.” 13

Standstill Agreements and Jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court

The effect of a standstill agreement on UPC jurisdiction was discussed in a recent decision issued by the Paris Central Division (CD) in proceedings including both a revocation action and an action for declaration of non-infringement.14

In particular, the defendant argued that the Court lacked jurisdiction to decide the case due to the breach by the plaintiff of a standstill agreement between the parties according to which a party has to give notice to the other party of its intention to file a lawsuit at least 90 days before any lawsuit is filed.

The first issue addressed by the Court was whether the standstill clause actually concerned the court jurisdiction or related only to the use of confidential information received from the other party. The Court decided that the wording of the clause at issue included an obligation to provide the other party with a prior written notice in relation to any “proceeding arising from or relating to a dispute over intellectual property” and thus rejected the plaintiff’s interpretation according to which the standstill clause applied only to proceedings using the other party’s confidential information.

The plaintiff also contested the validity of the standstill clause itself, claiming that it was contrary to the right of access to court and to a fair trial. The UPC disagreed with this argument providing a list of all the elements that were favorably considered when evaluating its legitimate purpose:

“it is aimed at giving the parties a ‘cooling-off’ period in order to enhance and enable an out-of-courtsettlement, is proportionate, as it is limited in time and appropriate to verify if an out-of-court settlement is possible, and does not undermine the rights of the parties (and of the claimants, in particular), as the wait for the lapse of the 90-days period does not appear to be detrimental to its interests and, in any case, no allegation has been made by the claimant on that point.”

Finally, the Court considered how a lack of jurisdiction can only occur

“when a different court or a different body (as an arbitration board) which is part of a different judicial system have the power to address the dispute (‘relative’ lack of jurisdiction) or when the situation brought to courts is not even abstractly configurable as a protectable right, pertaining to the administrative or the legislative power (‘absolute’ lack of jurisdiction).”

Based on these considerations, the Paris CD affirmed that “none of these situations is present in the situation at hand” and therefore concluded that “the violation of a standstill agreement does not constitute grounds for challenging the jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court.”

Basic Principles of Jointly Owned Patents under United States Law

In contrast to certain UPCA provisions and/or European national law when the UPCA may not apply (according to the criteria set forth by Article 7 of Regulation (EU) No 1257/2012), in the United States the rights of joint owners of a patent are governed by 35 U.S.C. § 262 which provides that “[i]n the absence of any agreement to the contrary, each of the joint owners of a patent may make, use, offer to sell, or sell the patented invention within the United States, or import the patented invention into the United States, without the consent of and without accounting to the other owners.” Subsequent and well-settled case law extends this right to allow joint owners to license the patent to third parties without obtaining the consent of or accounting to other joint owners.15

There is also substantial case law in the United States concerning the need to join all joint owners in patent litigation.16 Under such case law, a joint owner acting alone lacks standing to sue. As a result, by not joining a litigation one joint owner can disrupt the plans of another joint owner seeking to enforce a jointly owned patent against an infringer. U.S. courts have noted that the rule against involuntary joinder is well-established, and a contrary decision would upset the expectations of the parties.

Indeed, the requirement that all joint owners must join a patent infringement action trumps Rule of Civil Procedure 19 concerning required joinder of parties. In the Ethicon v U.S. Surgical case a joint owner of the patent did not consent to the suit against U.S. Surgical and as such Ethicon’s complaint did not include one of the joint owners of the patent.17 Thus, the Federal Circuit in a 2 to 1 decision dismissed the suit for lack of standing. Interestingly, Judge Newman in her dissent indicated that she would have applied Rule 19 to the facts of the case.

In light of the above, licensing and litigation issues related to jointly owned patents in the United States can and should be governed by agreement, so the wishes of all parties can be agreed upon in advance.

Joint Ownership of Unitary Patents

The Unitary Patent System has significant implications on jointly owned patents and certain aspects need to be considered at the time of filing an application for a European patent as significant issues extend beyond the grant procedure for European patents. Joint ownership, or co-ownership, is relatively common in many jurisdictions and also across jurisdictions especially in various

types of research collaborations and publicly funded research and development programs.

The Unitary Patent System provides which national laws will apply to a Unitary Patent as an object of property. However, joint owners can contractually establish the specific rights and obligations they prefer. Joint ownership agreements, of course, have been an essential tool to manage co-ownership of European patents before the start of the Unitary Patent System but their role have become even more critical now.

Representation of Joint Owners before the European Patent Office and the Unified Patent Court

In case of representation before the European Patent Office, if no common representative is appointed by joint applicants or proprietors, the first-named applicant or proprietor is considered to be the representative (Rule 151 EPC). Thus, the order of the listed joint applicants may become decisive early in the patent prosecution process.

It also should be noted that during the grant procedure, a formal request for unitary effect for obtaining a Unitary Patent must be filed by the proprietor of the European patent before the European Patent Office. In the case of joint ownership, the joint owners should have agreed on a common representative and whether to obtain a Unitary Patent. Even if the joint owners have agreed on a common representative, all the patent proprietors must duly sign the request for unitary effect.

Also, representation of joint owners in any proceedings before the UPC should be taken into account in agreements involving joint ownership. There are extensive rules on representation of the parties provided by the UPC Rules of Procedure under Chapter 3, which also apply to joint owners.18

Laws Applicable to European Patents as an Object of Property

The laws applicable to a Unitary Patent as an object of property is defined so by Art. 7(1) and 7(3) of EP-UE Regulation,19 which defines which national law shall be applied to a Unitary Patent as follows:

i. If the applicant of a European Patent as recorded in the European Patent Register had their residence or principal place of business in a UP/UPC member state on the date of filing of the European patent application, the national laws of that UP/UPC member state will apply.

ii. If i. above does not apply, but the applicant of a European Patent as recorder in the European Patent Register had their non-principal place of business in a UP/UPC member state on the date of filing of the European patent application, the national laws of that UP/UPC member state will apply.

iii. If i. or ii. above does not apply, then the German laws regarding a patent as an object property will apply (as the headquarters of the European Patent Office is located in Munich, Germany).

The order in which the joint applicants are listed is decisive beyond the grant procedure in terms of Unitary Patents. Namely, the order of in which the joint applicants are listed determines which national law is applicable to the Unitary Patent as an object of property according to Art. 7(2) of EP-UE Regulation.

The national law will then determine how the Unitary Patent can be assigned to other proprietors, what requirements and effects granted licenses will have, and what rights and obligations the joint owners have. Specifically, the firstly listed applicant is important. The firstly listed applicant in the European Patent Register in conjunction with its residence or place of business at the filing date will determine the applicable national law, which will impact all other joint applicants in accordance with Art. 7(2) of EP-UE Regulation. If neither the first nor any of the further applicants (in their listed order) are domiciled within the territory of the states participating in the Unitary Patent System nor have any place of business in the UPC territory, then German law will apply.

By the wording of Art. 7(2) of EP-UE Regulation, the applicable national law as determined on the date of filing cannot be changed. It will stay the same even if the order of joint applicants would for some reason be altered, if the applicant transfers the Unitary Patent to a third party or to an already listed joint applicant with residence or place of business in a different country, or later changes its place of business. Therefore, attention should be paid to the order of listing the joint applicants already at the time for filing a European patent application in order to avoid potential issues related to the applicable national law relating to a European patent as an object of property.

Opt Out from the UPC Jurisdiction by All Joint Owners

As discussed above, Art. 83(3) and 83(4) UPCA together with Rule 5 of the RoP, during the transitional period, establish so called opt out and opt in procedures enabling proprietors of European patents validated nationally in the UPC member states to choose whether or not their European patents remain in the competence of the UPC. Rule 5 RoP also stipulates that where the patent or application is owned by two or more proprietors or applicants, all proprietors or applicants must lodge the application to opt out.

The UPC Court of Appeal has already issued a decision confirming that a valid opt out application must be filed by or on behalf of all proprietors of all national parts of a European patent to be effective in Neo Wire-less v Toyota.20 In this case Neo Wireless LLC was the owner of European application EP 3 876 490 for all designated states. The German part of the application was transferred to Neo Wireless GmbH & Co KG in February 2023. Neo Wireless LLC filed an opt out for “all EPC states” in March 2023. The opt out application was not filed on behalf of Neo Wireless GmbH & Co and no consent was provided by Neo Wireless GmbH & Co in connection with the opt out application.

Toyota filed a revocation action against the German part of EP 3 876 490 before the Paris Central Division of the UPC. Neo Wireless GmbH & Co KG filed a preliminary objection on the grounds that EP 3 876 490 had been validly opted out from the jurisdiction of the UPC, and the UPC therefore lacked jurisdiction and competence to decide on the revocation action. The Paris Central Division as the first instance court held that the opt out filed by Neo Wireless LLC was invalid, because not all proprietors of all national parts had lodged the application as required by Article 83(3) UPCA and Rule 5.1(a) RoP.

Neo Wireless GmbH & Co KG argued that, according to the wording of Art. 83(3) UPCA, an opt out by any one applicant for a European patent should be sufficient. The UPC Court of Appeal found that Art. 83(3) UPCA required interpretation and determined that the object and purpose of Art. 83(3) UPCA make clear that the opt out application must be lodged by or on behalf of all proprietors of all national parts if there are more validations. Thus, the appeal by Neo Wireless GmbH & Co KG was rejected by the Court of Appeal, which held that the patent had not been validly opted out from the competence of the UPC as required by Article 83(3) UPCA and Rule 5.1(a) RoP.

Contractual Implications of Joint Ownership in Europe

It is obvious from the above that joint ownership of European patents whether traditionally validated or with the unitary effect raises a number of issues that must be considered in relevant agreements. Great variation regarding national laws and relevant caselaw applicable to joint ownership exists between different UP/UPC member states, which, if not understood early enough, can cause complexity in joint ownership and exploitation of jointly owned European patents.

At an early stage, joint owners should agree on the order that they will be listed as applicants on the European patent application, on appointing a common representative and how decisions regarding applying for national patents, a classical European patent with national validations and/or requesting unitary effect are made. It is also advisable to contractually set forth in detail matters related to prosecution and maintenance of patent applications including, for example, who will control prosecution and, if this is managed by one of the joint owners, how the other joint owners are informed and consulted and their rights and options related to prosecution and how costs are shared. It is also recommended to agree on what happens and what are the conditions that must be met in the event that one of the joint owners wishes to leave the joint ownership and/or wishes to assign its rights to a third party.

Rights regarding use and exploitation of the patent should be agreed upon as well including, for example, rights to grant licenses and sub-licenses, possible exclusivities and agreeing on fields and/or territories of use as well as potential revenue sharing. In terms granting licenses and sub-licenses, it should be agreed if a consent of the other joint owner(s) is needed as well as

possible conditions that must be met when granting any licenses.

Finally, rights and obligations to enforce, in particular jointly owned Unitary Patents but also classical nationally validated European patents, should be agreed upon including decisions to opt out and opt back in classical nationally validated European patents, keeping in mind that an application to opt out (and also the application to opt back in) must be done by all joint owners. In terms of enforcement, attention should be paid to who has a right to enforce, how the joint owners will cooperate in enforcement, how the burden of costs is carried, and how the possible damages will be shared.

The early case law of the Unified Patent Court is still based mainly on decisions and orders issued in the context of preliminary proceedings. While significant guidance can be gleaned already, future decisions on the merits will provide more specific information about how patent related agreements should be drafted in order to navigate the new European patent system effectively.

1. Filing and prosecution strategies in connection to the Unitary Patent System have been discussed in different contexts. See, for example, Hutterman, “Unitary Patent and Unified Patent Court, 2nd Edition,” 2023, p. 436-437, and Hoffman-Eitle, “The Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent: A Practitioner’s Handbook, 2nd Edition,” 2022, p. 24-30.

2. See also, for example, Hutterman, “Unitary Patent and Unified Patent Court, 2nd Edition,” 2023, p. 436-437, and HoffmanEitle,“ The Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent: A Practitioner’s Handbook, 2nd Edition,” 2022, p. 25-28.

3. Mala Technologies v Nokia Technology, Paris Central Division, UPC_CFI_484/2023, order of 2 May 2024, points 58-59.

4. AIM Sport Vision v Supponor, Helsinki Local Division, UPC_CFI_214/2023, decision of 20 Oct 2023, section 1.6 federal courts’ requirement that a plaintiff possess sufficient exclusionary rights in the patent to bring suit, and the Commission’s rule that the complainant must be an owner or exclusive licensee.

5. Alfred E. Mann Found. for Sci. Rsch. v Cochlear Corp., 604 F.3d 1354, 1358–59 (Fed. Cir. 2010); Ridge Corp. v. Kirk National Lease Co., No. 2024-1138 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 1, 2024) citing Univ. of S. Fla. Research Found., Inc. v. Fujifilm Med. Sys. U.S.A., Inc., 19 F.4th 1315, 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2021). The requirements to bring a patent infringement action at the US International Trade Commission do not require Article III standing. “Certain Active Matrix Organic Light-Emitting Diode Display Panels and Modules for Mobile Devices, and Components Thereof, Inv.” No. 337-TA-1351 Comm’n Op. at 13 (May 15, 2024) (“Insofar as the Commission has previously applied a constitutional standing requirement in the past or suggested that it applies to section 337 investigations, that precedent is hereby overruled.”). The ITC has recently reaffirmed that at least one complainant in every case must be an owner or exclusive licensee of the asserted patent and that “it is appropriate to consider precedent as to whether [complainant] is a ‘patentee’ who can bring a patent infringement action under 35 U.S.C. § 281.” Although the Commission noted that “[t]he terms ‘owner or exclusive licensee’ have been interpreted to be the same as the term ‘patentee’ in 35 U.S.C. § 281” by the federal courts, it left unanswered whether there is any difference between the federal courts’ requirement that a plaintiff possess sufficient exclusionary rights in the patent to bring suit, and the Commission’s rule that the complainant must be an owner or exclusive licensee.

6. Alfred E. Mann Found. for Sci. Rsch. v Cochlear Corp., 604 F.3d 1354, 1358–59 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

7. Ridge Corp. v Kirk National Lease Co., No. 2024-1138 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 1, 2024) citing Univ. of S. Fla. Research Found., Inc. v Fujifilm Med. Sys. U.S.A., Inc., 19 F.4th 1315, 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

8. 10X Genomics, Inc and President and Fellows of Harvard College v NanoString Technologies Inc., NanoString Technologies Germany GmbH and NanoString Technologies Netherlands B.V., Munich Local Division, UPC_CFI_2/2023, order of 19 September 2023

9. NanoString Technologies Inc, NanoString Technologies Germany GmbH, NanoString Technologies Netherlands B.V. v 10X Genomics, Inc., and President and Fellows of Harvard College, Court of Appeal of the Unified Patent Court, UPC_CoA_335/2023, order of 26 Feb 2024

10. 10x Genomics Inc. v Curio Bioscience Inc., Düsseldorf Local Division, UPC_CFI_463/2023, order of 30 April 2024.

11. Panasonic Holdings v Xiaomi Technology France, Beijing Xiaomi Mobile Software, Xiaomi Communications, Xiaomi H.K., Shamrock Mobile GmbH, Xiaomi Technology Netherlands, Xiaomi Technology Italy, Odiporo GmbH, Xiaomi Technology Germany, Mannheim Local Division, CFI_219/2023, CFI_218/2023 and CFI_223/2023, orders of 30 April 2024.

12. Panasonic Holdings v Guangdong OPPO Mobile Telecommunications, OROPE Germany, Mannheim Local division, CFI_216/2023, orders of 16 May 2024 (Machine translation from original in German language).

13. Panasonic v Xiaomi, cited in note 11.

14. Tandem Diabetes Care, Inc., Tandem Diabetes Care Europe B.V. v Roche Diabetes Care GmbH, Paris Central Division, UPC_CFI_589997/2023, decision of 10 May 2024.

15. Schering Corp. v Roussel-Uclaf SA, 104 F. 3d 341 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

16. STC.UNM v Intel Corp., 767 F.3d 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

17. Ethicon Inc. v U.S. Surgical Corp. 135 F.3d 1456 (Fed. Cir. 1998).

18. Regarding representation, in a recent decision by the Paris Central Division UPC_CFI_164/2024 on 2 July 2024, the court noted that “the fact that a party’s representative also carries out active administration tasks on behalf of the represented party and that he may be directly interested in the outcome of the case is not decisive in order to consider that the representative is not independent for the purposes of the application of Rules 290, 291 and 292 ‘RoP’.”

19. Regulation (EU) No 1257/2012 regarding implementing enhanced cooperation in the area of the creation of Unitary Patent protection.

20. Neo Wireless v Toyota, Court of Appeal of the UPC, UPC_CoA_79/2024, order of 4 June 2024.