We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

No cookies to display.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

No cookies to display.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

No cookies to display.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

No cookies to display.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

No cookies to display.

Juergen Graner

Founder and CEO

Globalator

San Diego, California, U.S.A.

Juergen Graner

Founder and CEO

Globalator

San Diego, California, U.S.A.Operational excellence is probably the most undervalued intellectual asset in business practice when compared to technology and brand. However, building a business with strong operational excellence has the potential to create a sustainable competitive advantage.

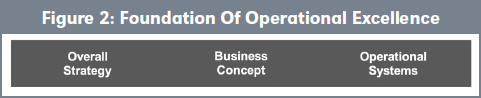

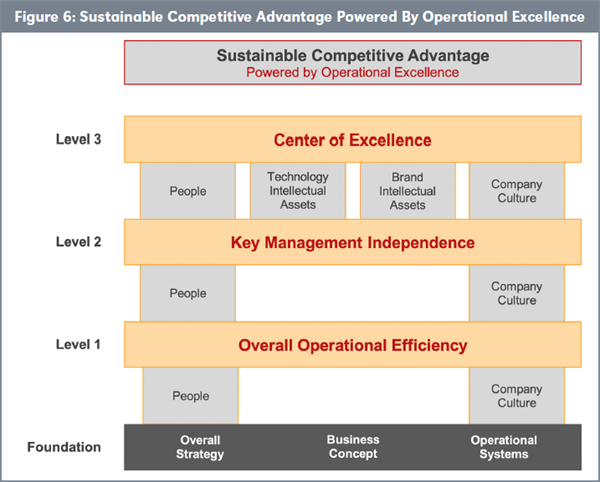

The foundation to building operational excellence consists of the following elements: a solid overall strategy, a well-defined business concept, and operational systems that support the business. The three levels of operational excellence are overall operational efficiency, key management independence, and a center of excellence. Those levels are supported by people with their capabilities and an overall enabling company culture.

The two intellectual assets, technology and brand, are further important support elements, especially for a center of excellence within an organization. For true sustainable competitive advantage, all levels and support elements of operational excellence need to be established.

Sustainable competitive advantage is considered by many CEOs as the Holy Grail of business advancement. It is achieved by not only focusing on gaining a temporary edge, but also effectively managing a company or organization in ways that enable it to maintain a long-term advantage over competitors. Unfortunately, the pressure for business decision-makers is often more focused on the short term, rather than on the long term. Incentive schemes for CEOs as well as employees are regularly driven by next-quarter results instead of value generation that lasts. Operational excellence is a key component—if not the most important one—to creating sustainability and long-term value.

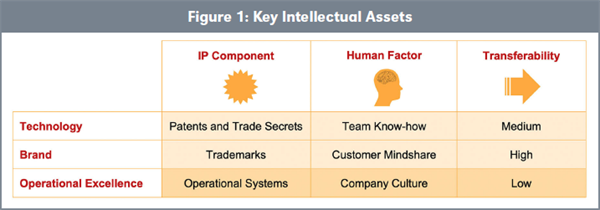

Operational excellence is a key intellectual asset that works in conjunction with technology (typically supported by patents and trade secrets as the key intellectual property (IP) component) and brand (supported by trademarks as the key IP component). While intellectual assets and IP in general are unfortunately already undervalued as an important part of business strategy (especially at small and medium-sized entities), operational excellence is probably the least appreciated intellectual asset. Part of this is probably rooted in the fact that there are no standardized protection mechanisms available, like patent or trademark registrations. Operational excellence is all about management, skill and people—all elements that are often considered the “fluffy stuff” that is difficult to put into numbers (except that those enterprises that master operational excellence can usually show higher profitability). It seems to be easier for CEOs to announce how many patents they have and what the brand value of their business is, than to talk about their operational excellence.

Moreover, operational excellence is also highly misunderstood by business decision-makers. Many CEOs believe that simply having documented standard operating procedures (SOPs) or ISO 9000 certification will take care of it. The purpose of this article is to provide a simple strategic model for operational excellence that on the one hand is easy to apply, but that also captures the breadth of the subject. It should illustrate how powerful operational excellence can be in building value within a company and how it has the potential to become the core driver of sustainable competitive advantage.

The model presented in this article includes a foundation (consisting of overall strategy, business concept and operational systems) upon which the following three levels of operational excellence are built:

Each level is supported by pillars that enable the individual level to be built and sustained. These pillars include people, company culture, technology intellectual assets and brand intellectual assets (see Figure 6 at the end of this article for an illustration of this model).

Intellectual assets are key value drivers of business success. This article builds upon the understanding that an intellectual asset consists of an IP component enabled by a human factor.1 Ultimately, people are the most important asset of a company, so CEOs should make sure that they are managed well. Figure 1 provides an overview of the key intellectual assets. The intellectual assets technology and brand can not only be value drivers themselves, but, also play an important support function for operational excellence, as this article will elaborate on later.

Operational Systems—The IP Component

The IP component of operational excellence is fundamentally different from that of technology or brand. A technology can be protected by patents, trade secrets and similar instruments, and companies have defined mechanisms for protecting those against violators. Similarly, a brand can be protected by trademarks, and those can be defended accordingly. For both technology and brand, governments around the world have established organizations that will certify the rights defined by a patent or trademark (e.g., the EPO and the EUIPO in Europe, or the USPTO in the U.S.A.), and businesses are well advised to take advantage of that. However, the IP component of operational excellence is arguably represented by the operational systems that a company follows (e.g., standard operating procedures). It should be part of any trade secret protection policy (which is also a tool for protecting elements of technology IP in conjunction with patents), yet there is no register for it. Claims that operational systems have been copied by competitors can often be rather difficult to prove in legal proceedings.

Company Culture—The Enabling Human Factor

Company culture refers to a shared set of beliefs, values and behaviors that people within a company generally subscribe to. No two company cultures are ever the same, since the individual culture depends on surrounding cultural factors (e.g., the country where an organization is located) and intrinsic cultural factors (the way founders, CEOs and senior managers have run the business on a day-to-day basis). To some degree, culture as the enabling human factor of operational excellence also has an impact on technology and brand intellectual assets. While the team know-how is primarily what enables the technology intellectual asset, it makes a difference under what company culture that team know-how is put to use. For example, a company where part of their culture is to include outside sources for technology innovations (open innovation) will likely be able to develop a stronger and wider technology base than a company where the culture dictates that everything should be invented only within the company. Similarly, while it is primarily the customer mindshare that enables the brand intellectual asset, a strong corporate culture that focuses the entire team on putting customers first will likely build a stronger, more reputable brand than a company where employees believe customer complaints are simply annoying.

While it may be difficult to prevent the copying of the operational excellence IP component, the good news is that the real value in operational excellence lies in the company’s culture—something that is rather complex and difficult if not impossible to copy. True operational excellence is difficult to achieve, since company culture is the enabling human factor. Every company has a culture. The only question is if the culture just happens, or if it is managed proactively and systematically. A culture is usually built from the top down. Symbols and active examples by leaders and managers play an important role in shaping it, willingly or unwillingly.

Company culture consists of two components. First of all, there is the overall culture element that cuts across all departments and functions. Second, any company forms sub-cultures to a higher or lesser degree as it grows. Typically in science- and engineering-driven companies, for example, the R&D and/or manufacturing departments of the company have a different culture from the marketing and sales department. Sometimes there are different cultures that cut across departments when, for example, those people that smoke meet regularly outside the building (in many countries, smoking inside buildings is no longer permissible) and establish a special bond around their cravings. There are numerous examples of sub-cultures that form within a company, and as long as they are brought together in a productive way under an overall culture, it is fine to have them. Unfortunately, many CEOs do not pay enough attention to managing their overall culture and the sub-cultures. Moreover, company cultures evolve and change as companies grow, and this is a process that is often not proactively managed by business decision-makers.

Transferability

There is a fundamental difference between technology, brand and operational excellence in terms of transferability. Transferability is important when it comes to strategic transactions (e.g., alliances, licensing, spinoffs, acquisitions, and divestments).

Brand intellectual assets are generally the easiest to transfer and therefore offer high transferability. While there are exceptions, in most circumstances for customers it does not really matter who actually provides them with a product or service as long as it continues to fulfill or exceed their expectations.

Technology intellectual assets can be transferred easily only insofar as the patent rights alone are concerned. However, it gets more difficult when trade secrets and know-how also need to be transferred, which is common. Therefore, transferability of technology intellectual assets should be considered medium.

Operational excellence intellectual assets are by far the most difficult to transfer. Some would even argue it is impossible to transfer such assets entirely. Almost everything that a company does can be copied by another entity, except its culture. This is not only a problem in transfers between different companies, but also between different locations of the same company, especially when they are in different countries. This illustrates well that culture is not only company-specific, but also location-specific. The upside of this is that operational excellence, to some degree, has a natural built-in protection mechanism.

In order to achieve ultimate operational excellence, not only does the foundation with its operational systems have to be considered, but also overall operational efficiency (level 1) and key management independence (level 2), as well as a center of excellence (level 3).

3.1. Foundation

The foundation of operational excellence consists of the overall strategy, the business concept, and the operational systems (see Figure 2).

Overall Strategy

It makes a difference if a company is built as a generational business (build-to-grow) or built towards an exit (build-to-sell).2 Many high-growth technology businesses follow a build-to-sell strategy. They often have risk capital (from business angels and/or venture capital funds) to fund their growth, and who require an exit. There are also founders that simply decide themselves that selling their business is what they would like to do for a number of personal reasons. Therefore, the business needs to be prepared to work in the hands of a much larger organization at some point in time. The overall strategy of a company entails much more than the general direction (e.g., build-to-grow vs. buildto- sell). Depending on the business, it includes choices like what markets to serve, products and services to be offered, goals to be achieved within a defined time frame, and much more. A strategy should be adjusted annually or when certain events arise that require a change in direction.

It is actually mind-boggling when individual people in the vast majority of companies are interviewed about the strategy of their business, especially at small and medium-sized enterprises (SME). Individuals within different units of the same company often either have a completely different view of the strategy, or do not know certain key elements. However, a company can only grow quickly and efficiently if everyone moves in the same direction. Nevertheless, corporate strategy is usually not communicated well, or is only present in the minds of the leadership team. A good way to overcome this is to create a well-defined strategy that fits on a single page, has some graphic elements that enhance the message (the saying “a picture says more than a thousand words” definitely applies here), and everyone in the company from the CEO to people working at the bottom of the organizational chart knows the strategy and applies it. Having such a graphically enhanced strategy is actually a good starting point for fixing deficits in operational excellence.

Business Concept

Somehow related to the overall strategy is the business concept, since it also provides direction. While many companies establish a clear vision, mission and value statement, they fall short in defining how they make money. The business concept does exactly that. It defines how a company operates by defining in broad strokes what the company does and how it does it. For example, the business concept might entail that a company does not manufacture its products in its own facilities, but outsources that activity to longterm alliance partners. Alternatively, a business concept might entail that it owns and operates its own warehouses with a proprietary system for managing the flow of goods. If a company uses open innovation as part of its R&D efforts, then this is also something worthwhile to include in the business concept.

Contrary to a company’s vision, mission and values, the business concept is usually only shared internally and with potential investors, and is a simple way to understand in broad terms how the business operates. It also has a big impact on operational excellence, because if many elements of the value chain within an organization are outsourced to third parties, then those elements by definition are out of scope of the active management and therefore much more difficult to influence.

Operational Systems

Almost any company, if prompted, will be able to claim that they have some form of operational systems. An operational system is usually documented in SOPs and ensures consistent management of all day-to-day activities of a company: from product/service ideation right through until the product/service has reached the customer and beyond. This also represents the core IP component of operational excellence.

Smaller companies and startups in their early years may have very basic systems that use simple spreadsheets. Others use a sophisticated ISO 9000, Six Sigma and/or total quality management (TQM) process, which is supported by a fully-fledged enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. These systems really need to evolve properly along with the growth of a business, always having the next two iterations of growth in mind. Changing operational systems completely through a reengineering process has the potential to impact business growth for one to two years.

3.2. Overall Operational Efficiency (Level 1)

Achieving operational efficiency is probably the most logical first level of operational excellence that most business managers would say they engage in, to some degree. It is important, however, especially for small and medium-sized businesses with limited resources, to define what level of operational efficiency is needed in which company function. It is simply not realistic to have the highest possible operational efficiency throughout the entire value chain of a company, so setting priorities is important.

For a company in a build-to-sell setting, operational efficiency can have a significant impact on the valuation of a business. While it is not visible as a separate line item on the financial statements, it impacts the metrics of the business. Most acquirers have a rather key-financials- focused valuation approach to determining their offer price. The three key financial performance drivers for valuations are high growth rate (top-line), high gross margin and high profitability (bottom-line). Various functions can have an impact on each of these parameters, as outlined by the following examples:

Operational efficiency is built on the foundation of operational excellence (overall strategy, business concept, operational systems; see Figure 6), and it has two pillars that support it: people and company culture (see Figure 3). However, without the right foundation, operational efficiency can become like a drone where the remote control fails and the owner simply hopes for the best.

The first pillar of operational efficiency consists of the people within the organization that have the capabilities to support it. Those capabilities, especially in relation to operational efficiency, are highly impacted by experience in combination with creativity. These are basic traits that a person needs to have in order to create high value for a company. When it comes to fine-tuning the operational systems to the highest level of efficiency, experience becomes very important. The issue with experience is that experienced people require higher remuneration and a capabilities audit often reveals that the required experience level might not be available within an existing team. This necessitates hiring outside talent for new key functions, or replacing those people who simply lack the experience needed to drive company growth. Evaluating the experience part of a new key hire to improve operational efficiency is rather easy. More complex is the task of understanding if someone also has the creativity needed. Often, new hires from large corporations do not do well in smaller high-growth company settings. They have great experience in managing one little component within a well-established system that consists of a multitude of specialists. SMEs often cannot afford to hire individuals for each function, therefore cross-functional training and creative thinking is a must, which is often lacking in individuals whose sole experience has been in large corporations.

Having the right people for the right function for the right company size is only one-half of the equation. People also need to fit the company culture. As mentioned before, no two cultures are really the same, but some are more similar than others. Therefore, it is important to spend time evaluating the cultural fit when recruiting, which is an important function for a growing business. Conducting extensive personal interviews with assessment centers utilizing specific standardized tests and hiring professional recruiters can help with this. Things get even more complicated when a company finds itself in a situation where it requires a cultural shift while growing. This means that someone needs to be hired who not only fits the current culture, but also has the capabilities to support the shift to a new one. One should keep in mind that company culture drives behavior and behavior impacts motivation and performance, both positively and negatively.

3.3. Key Management Independence (Level 2)

Having key management independence is an important risk management tool for companies to ensure that they do not go under if key people leave. There are two dimensions to key management independence. First of all, there is independence from the founder or founding team. Second, there is independence from key functions or know-how carriers within the organization. Basically, any person in a company that could not take a three-month vacation without the company being seriously affected falls into that latter category.

Successful companies are usually founded by entrepreneurially-minded individuals or small teams that have the ability to create excitement for others to join them; otherwise, they would not be successful. This is often combined with very deep know-how in one area of technology and/or business. For example, life science companies are often founded by outstanding scientists and engineers with deep knowledge in one aspect of technology. While this is a major asset during the formation and the initial growth phase of a company, it may become a major liability as the business grows when this knowledge is not transferred to others. To make matters worse, some entrepreneurs have the tendency to associate their personal brand with the company brand, so the company is seen by customers to be synonymous with the founder or founding team. The dependence on the founder(s) is so common that many potential purchasers of a business would generally require the founder(s) to stay on board several years after an exit.

Besides the founder(s), there are many other functions within a company that are run by individuals who are very important to the business. At the management level, this dependence is mitigated if the individual manager actually delegates well (which, by the way, is also a good practice for founders to follow). Unfortunately, in many companies strong leaders in management functions establish their own “kingdoms” within the company, which creates a high dependence on those managers. At the individual level, many companies have employees who may not have a management function, yet they possess know-how that no one else has and which is critical for successful continuation of the business.

Reducing key management dependence is the second level of operational excellence, and it is rarely addressed in small to medium-sized companies. This level is also supported by the same two pillars as the previous level: by people and company culture (see Figure 4).

From a people pillar perspective, a business can be glad to have great leaders, managers and subject-matter experts. As long as those individuals are with the company, everything works well. From a founder(s) perspective the issue arises when they transfer the business to someone else, either from one generation to another within the family, or through an exit process (the latter is common for high-growth technology businesses). It is therefore important to establish a strong professional management team early on as the company grows. The founder’s function then becomes more that of a visionary and leader, rather than a CEO running daily operations. Individuals with critical know-how need special attention from a management perspective to ensure that any kind of dissatisfaction that could lead to a departure from the business can be mitigated early on. However, people may also have accidents or serious illnesses that take them out of the workforce suddenly, and a business needs to be able to handle that by capturing such expert know-how as much as possible in writing and by training others, thereby building up potential successors.

The issue with company culture is that it is shaped through the omnipresence of the founder(s). They shape what the culture looks like, and that shape often reflects their own personality, instead of having established a professionally managed culture that is independent of the founder(s). A good way of training a business to shape its own culture is usually for the founder(s) to take extensive vacations during which they are not reachable. For key individuals within the company, a positive company culture that encourages them to stay and perform is the best guarantee of keeping them onboard, and at least mitigates the risk of them voluntarily leaving or, even worse, joining or becoming a competitor.

3.4. Center of Excellence (Level 3)

Building a center of excellence is the third level in the operational excellence spectrum. This means that a company establishes itself to hold a position in one market niche or function where it can perform better than most of the competition, and in a best case scenario strive for “best in the world” performance. In order to achieve true center-of-excellence performance, physical assets as well (e.g., locations, machinery, and equipment) often need to be expanded. A common mistake made by CEOs is to believe that their whole company needs to consist of centers of excellence. This is missing the point, especially for SMEs. It is about focusing on and dominating one segment, while allowing others just to be good.

Even large companies show that one center of excellence can carry a company a long way. For example, while Amazon is probably good at many things, their true center of excellence that has continued to provide them with a sustainable competitive advantage in the e-commerce space is arguably their capability to get the right products to the right customers in the shortest period of time in the most efficient way (basically, logistics). This is not something Amazon came up with recently. Already in the late 1990s, when all other competitors were simply building attractive websites, Amazon built extensive distribution centers across the U.S., supported by the most efficient operational systems. They quickly established themselves as the most reliable company in the e-commerce space, which continues to provide them with a competitive edge.

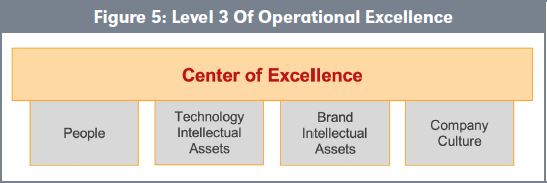

While a center of excellence also has people and company culture as support pillars, the other intellectual assets (technology and brand) come into play as important elements as well (see Figure 5).

Like at the previous two levels of operational excellence, it is important to recruit and keep the right people with the right capabilities to support building a center of excellence. The company culture also needs to be built to be able to support the center of excellence.

From a technology intellectual assets perspective, it is important to understand the chosen center of excellence early on. Technology advancement and patent protection are expensive activities, and the budget for them should be focused on the segment that the company wants to dominate. If a product or service requires several technologies and the budget is not sufficient to develop a leadership position, it makes sense to focus on one technology area that the company can “own.” This strength in one area can be used as a bargaining chip to gain access to other technologies through strategic transactions in areas where the company might have a weakness. Experience shows that it is usually better to be best in one segment and fair in all others that are necessary for business success, than being average in everything.

From a brand intellectual assets perspective, a company should let the market know that it is a leader in its field. Constantly communicating inside and outside the desired leadership position has the potential to create a self-fulfilling-prophecy effect. Obviously, a company has to have some strengths first to avoid making any claims that cannot be substantiated. The interesting marketing effect that happens if a brand is seen as world-class in one area is that it is assumed to also be world-class in other related segments. Provided that other products and services can at least be provided with a good customer satisfaction result, this association with greatness in one area can work very well for companies. At the same time, marketing managers need to be careful to not overdo it and make unfounded claims. It has been proven repeatedly by companies all over the world that building a brand takes a long time—but destroying it can happen very fast. Especially in today’s hyper-connected world: word about non- or under-performance spreads fast.

To have one true center of excellence as a company that is on a build-to-sell pathway has one additional advantage. It also secures the future of the employees. Many founders not only like to have a great financial result, but also want to secure the employees’ future once the business is sold. A center of excellence can provide the best of both worlds: basically, it’s an employee insurance policy that also makes money.

While the strategic model presented in this article utilizes numbered levels (see Figure 6), it should not be seen like a pyramid that has to be approached from bottom to top, one after another. This would be a misapplication of this concept. It must be taken in the context of the individual situation and applied with creative strategic thinking in mind. Here are a few examples that should illustrate how the model might be used differently in different situations:

4.1. Startup (Build-to-Sell)

For a startup that is on a build-to-sell pathway to eventually sell within five to seven years, the starting point should actually be Level 3. By understanding the market with customer needs and competitor capabilities, it is often very clear where a center of excellence would make sense. It is fine to adapt that later on as the business develops, but it helps to focus the limited resources early on. Advancing in one center of excellence at an early stage also helps to secure additional investors as the business grows.

With the center of excellence in mind, the foundation can be established by clearly developing an overall strategy and business concept that support that center of excellence. As the business grows, operational systems should be established (still part of the foundation), followed by developing strong operational efficiency (Level 1), especially in the center of excellence relevant area. Moreover, building independence of key employees (Level 2) is important along the way.

At least one to two years before the business is sold, the founder(s) should start to establish a capable management team that can take the company to the next level. The founder(s) start to grow into a visionary role.

4.2. Turnaround

When a newly hired CEO steps into a turnaround situation, the starting point is likely to create an interim overall strategy and business concept quickly (foundation), which can be adapted along the way. The next step is to evaluate the operational systems and pay attention to overall operational efficiency (Level 1). In this case, the initial focus is not on a center of excellence, rather it is on finding those areas in the business where operational efficiency improvements can have the fastest effect (quick wins). In a turnaround, the key task is to stop the bleeding and ultimately be able to steer the company into calm waters. This also means relying on key subject matter experts within the company without worrying too much about the dependence on them.

Once the business is back to profitability, a reengineering process can begin, and establishing a center of excellence (Level 3) will be one of these tasks.

4.3. Family Business (Build-to-Grow)

As a CEO of an established family business that has legacy in mind and reviews the model presented here for potential applicability, the best starting point would probably be the foundation. Having a solid strategy and business concept that every employee understands combined with a robust, formalized operational system is an important driver for the business.

Once the foundation is clearly defined (maybe it is already), the primary focus should be on overall operational efficiency (Level 1). As family businesses usually do not have great access to growth capital, the operational efficiency should focus on overall distributed efficiency that ensures solid profitability. Uncontrolled growth can be fatal for a family business.

Building a business with several generations in mind means that diversification of the business is an important safety net for securing the long-term survival of the business. Most business segments are subject to market trends and, when one business does well, another might suffer. Therefore, from a build-to-grow perspective it makes sense to build several separate businesses with each having its own center of excellence (Level 3).

From a family business CEO perspective, independence of the business from the leadership (Level 2) must be considered, and better sooner than later. Having a strong second-level leadership team that is comfortable in their existing role is important, since the CEO position might not be available for a long time, if at all. Sometimes the next generation might step into the CEO role; alternatively a professional CEO is hired.

Operational excellence as an intellectual asset is a key component to achieving sustainable competitive advantage, which is often considered the Holy Grail of business advancement by many business leaders.

A great foundation (overall strategy, business concept, and operational systems) combined with overall operational efficiency (Level 1), key management independence (Level 2) and a center of excellence (Level 3) provide the right elements for achieving operational excellence at a level that enables sustainable competitive advantage (see Figure 6).

The pillars supporting all these levels of operational excellence are the people within an organization and the company culture as the glue that holds them together and enables them. Technology intellectual assets as well as brand intellectual assets can play an important supporting role in establishing a center of excellence.

While all factors of the model presented (see Figure 6) can play an important role in achieving ultimate success with operational excellence, the implementation level and order of the elements depend highly on the given situation. A startup requires a different order and focal points than a turnaround situation, or a family business that is built for legacy.

Reviewer and editorial support were provided by Adéla Dvořáková, Ilja Rudyk and Thomas Bereuter.