Beat Weibel

Siemens AG,

Chief IP Counsel, Munich, Germany

Beat Weibel

Siemens AG,

Chief IP Counsel, Munich, Germany Rudolf Freytag, PhD

Siemens AG,

Head of Licensing and

CEO of Siemens Technology Accelerator GmbH, Munich, Germany

Rudolf Freytag, PhD

Siemens AG,

Head of Licensing and

CEO of Siemens Technology Accelerator GmbH, Munich, GermanyDigitalization, with its enormous opportunities, is the dominant game-changer of the moment for every company. In this context, many companies are wondering what the right intellectual property strategy ("IP strategy") might be—because such a strategy must on the one hand effectively protect the business of the future. On the other hand, changing conditions make that same future very uncertain. One method has been tested in practice and can offer such protection: a value-driven IP strategy together with a value-driven business strategy. The authors show from their own experience how this approach works in both theory and practice. A value-driven IP strategy makes IP a unique strategic competitive tool for businesses.

Many companies still believe that the number of their invention disclosures or patent applications and the size of their portfolio of granted intellectual property rights is an important yardstick of their capacity for innovation. So they invest money and resources to apply for as many patents as possible for the inventions from their research and development departments.

There are different ways to realize the value of an IP right, however, ultimately the value of these intellectual property portfolios for business emerges only when a company must actually enforce its rights against an infringer and prevent the infringer from interfering with the company's own market presence. At that point, disenchantment often sets in, because the allegedly strong IP portfolio proves to be legally difficult or almost impossible to enforce. And the company realizes that while it has many intellectual property rights, it does not have the appropriate ones. The same also often applies when the company tries in vain to license out parts of its IP portfolio on attractive terms.

Digitalization presents many companies with an urgent question: What is the best intellectual property strategy for effectively protecting future business with the right intellectual property rights?

The goal is to make the most out of the rich opportunities of digitalization, keep the risks manageable, and ensure effective IP protection for future business—despite a highly dynamic market and the associated uncertainty.

Based on the authors' many years of experience from the viewpoint of both established companies and startups, a clear, value-driven IP strategy can provide precisely this effective protection for future business. This article shows how this goal can be achieved, and what should be given particular attention to in this regard. It also provides a deeper view of specific challenges of digitalization, together with the future expanded understanding of a patent attorney's profession.

Customers do not buy a product or a service. Customers primarily buy a customer benefit, for which they are willing to pay a certain price. For that reason, a company competes with other companies to provide customer benefit. Hence any business strategy, and any IP strategy that supports it, must consistently be "value-driven" [1].

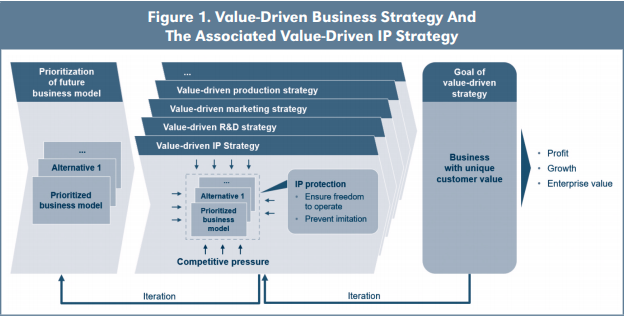

Figure 1 shows the basic concept. The ultimate goal of a value-driven business strategy is to establish a business with a unique and competitive customer benefit. A business's financial figures, such as profit, growth and enterprise value, then become criteria for how effectively and efficiently this value-driven business strategy is being implemented in operational terms. What can happen if one mistakenly focuses on financial figures rather than customer benefit as primary management parameters has been shown more than clearly by the fate of many companies that have committed themselves to maximizing shareholder value.

Figure 1 shows that the pathway to a business with unique customer value has two phases. In the first phase, one must prioritize what future business model shall be implemented. This prioritization must then in a second step be translated into function-specific strategies: for example, research and development, marketing, production, and of course, IP. In the event of new findings, it may be necessary to revise the prioritized business model and the functions' individual strategies in an iteration loop. For safety's sake, in any case the prioritization of the business model should be reviewed at least once a year, for example during the budget planning process.

A business model means a description of what customer benefit an organization wants to generate for which customers (the customer perspective) and how the organization is supposed to provide this customer benefit (the operational perspective). In other words, a business model answers two questions:

Prioritizing the future business model in the first phase in Figure 1 means carefully considering a number of questions: What are the hypotheses about customers, markets, technologies, the competition, and other influencing factors? And if those hypotheses are valid, which business models will be attractive for the future, which business model is the preferred one, and which models are considered interesting alternatives? The underlying hypotheses must be tested carefully with market studies, interviews with customers and experts, product prototypes, pilot sales, and similar efforts.

All functions within the company should cooperate in developing and prioritizing the future business model and its alternatives, including strategy, innovation management, research and development, marketing, production, finance, and of course also the IP function. At established companies, as a rule these functions are performed by departments; at startups, especially in the initial phase, they all will have to be taken care of by the founders. Nevertheless, it's important for startups to look at their business model from the viewpoint of all these functions.

The result of the first phase in Figure 1 is that all functions within the company have a shared and coordinated understanding of what the company's future business model will look like. In highly dynamic markets, alongside the prioritized business model, there will also be alternatives that must be considered as matters advance, at least as a fallback option. To keep complexity low, however, the number of alternatives should be limited.

As an example, let's consider a fictional startup company that has invented an innovative wheel-hub motor that is very well suited for driving electric scooters (eScooters), which are now becoming a more and more popular means of short-distance transportation even among adults. In scooters, this wheel-hub motor has significant advantages over other electric motors, most of which require a transmission: It is a more efficient drive, and can also be used as a braking system which very efficiently feeds braking energy back into the battery, thus greatly increasing the range of travel.

To prioritize their future business model, our eScooter founders apply the Business Model Canvas method [2], which is widely used among startups and now quite popular among established companies as well. It allows them to document the main components of a business model in an easy-to-view, easy-to-understand form, and to discuss them in workshops.

The founders discuss a variety of business models, each of which they map in Business Model Canvas displays. They choose "eScooter sales" to private individuals as their priority business model. And they intend to position themselves as the top high-end premium brand for electric scooters, using the wheel hub motor as their unique selling proposition. Alternative business models would be "eScooter sharing," i.e. offering large numbers of eScooters for short-term rental in cities, or a "wheel-hub motor supplier" that sells the wheel-hub motor as a component to electric scooter manufacturers or system integrators.

In the second phase in Figure 1, the function-specific value-driven strategies are developed, such as the R&D strategy, the marketing strategy, the production strategy, and of course the IP strategy. Here the shared interdepartmental understanding developed during the first phase in Figure 1 is an indispensable prerequisite for these function-specific value-driven strategies to be genuinely coordinated with one another and focused on the same goal, namely creating a business with a unique customer benefit and thus a competitive advantage.

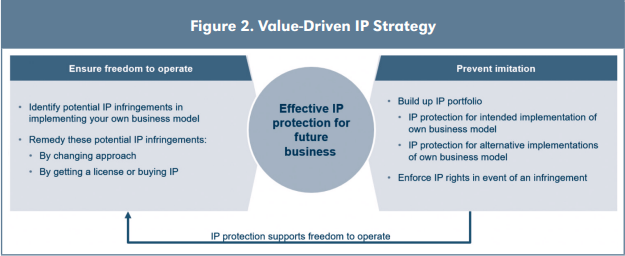

The objective of a value-driven IP strategy is to protect the future business model and its alternatives as effectively as possible with IP, thus helping to provide legal safeguards for the competitive advantage of a unique customer benefit. Here, two different tasks must be performed, which are shown in Figure 2:

As the arrow on the bottom of Figure 2 shows, "preventing imitation" supports "ensuring freedom to operate," because IP protection for one's implementation of a business model also safeguards one's freedom to operate.

To ensure the freedom to operate, first of all, one must check for all relevant countries whether implementing one's future business model or one of its alternatives will infringe any IP rights of third parties, such as patents, utility models, designs, trademarks or copyrights—all in all, a complicated but necessary task. If the implementation is not "free from third-party rights," then a remedy must be quickly found. Two basic approaches are possible, as shown in Figure 2:

To prevent imitation, advantage should be taken of the fact that IP rights are prohibitive rights. As Figure 2 shows, it is important to build up an IP portfolio that can be asserted legally and that has the following characteristics:

Like all other functional strategies, a value-driven IP strategy contributes to creating a unique customer benefit. But it differs from them very significantly in several points:

Because of its clear orientation to creating a unique customer benefit and using a prioritized business model as a basis, a value-driven IP strategy is very well suited for any company in a dynamic environment, and thus especially for today's era of the Digital Transformation. However, digitalization has special characteristics that should be considered when applying a value-driven IP strategy. These characteristics will be discussed, at least briefly, below.

As digitalization advances, obviously more and more attention has to be paid to how software is handled in developing an IP strategy [3]. There is still a misconception, as widespread as it is fatal, that software cannot be protected through IP, and thus there is no need to worry about it:

Digitalization is more than just a technical revolution. It's a revolution in the exchange of information within, and especially between, companies. Since this information exchange comes at practically no cost, it makes business ecosystems possible, like those of Amazon, Uber and Airbnb [4]. These business ecosystems are partnerships among established companies, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and startups. From the customer's point of view, this means that customer value is generated by the combined value added by all partners in such an ecosystem, and no longer by the value added by just one of the partners alone.

The value-driven IP strategy described above has proved its worth in numerous practical instances, at both established companies and startups. Nevertheless, many companies still—to some extent unconsciously—take a different approach: an invention-driven IP strategy.

In a traditional, invention-driven IP strategy, the starting point is that an inventor within the company believes he or she has invented something innovative that is of interest to the company and eligible for protection. Whether an intellectual property right is applied for, and how it is drafted, depends not so much on what the inventor and the patent attorney know about the company's current and future planned business model, but rather on the desire to apply for as many patents as possible, or it may be driven by considerations of the inventor's rights.

And precisely this is the core difference to a value-driven IP strategy, where the goal is to selectively protect the prioritized business model that has been coordinated across function boundaries. Thus, IP is selectively and actively procured with a focus on whether an idea is worth protecting, rather than simply eligible for protection. Moreover, an invention-driven IP strategy generally does not include the early, selective safeguarding of freedom to operate as does a value-driven IP strategy (see Figure 2).

All in all, then, a value-driven IP strategy leads to effective IP protection for future business, while an invention-driven IP strategy generally only achieves an unclear protective effect.

The difference between a value-driven IP strategy and an invention-driven IP strategy becomes less and less the longer a company is in existence and the less the business environment changes. In the latter case, a company usually has an adequate IP portfolio, and all employees are quite familiar, from experience, with the business model and its further evolution and they intuitively know what is needed for a successful IP strategy.

But precisely that environmental stability is not available in today's era of digitalization. The more uncertain the future, the more sharply the prioritized future business model and its alternatives will diverge from one another and from the present situation. In the same way, the IP strategy must ensure that all of them are protected as well as possible. That makes applying a value-driven IP strategy a competitive advantage in the digital transformation.

Patent attorneys' present understanding of their profession is still very much oriented to the invention-driven approach of an IP strategy, which is focused on the invention and its eligibility for protection.

But since digitalization necessarily requires a transition of one's IP strategy to a value-driven approach, patent attorneys' understanding of their own profession must also change accordingly:

In particular, that also means that in the future, patent attorneys will need to be quite familiar with the company's strategy, as well as its market, technology and competitive environment, and must be able to speak the same "language" as the strategy, product management, development and production departments. That particularly also includes working with the Business Model Canvas. It is the patent attorneys themselves, not their colleagues in other functions, that need to do the work of making the transition from the strategic level to the IP specialist level, and thus especially of translating the strategy into legal language.

So that they can perform this role in developing a value-based IP strategy, in the future patent attorneys will need to have a high level of communication skills, creativity and team management. In this way, IP work will become an integral part of business, and thus the contribution of the IP function to business success will become clear to all other functions in the company.

Patent attorneys with this expanded understanding of their profession will make a crucial contribution toward developing value-driven IP strategies at companies, and thus achieving a competitive advantage in the Digital Transformation. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN):

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3470192

[1] Dodgson, M., Gann, D.M., Phillips, N. (2014) "The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management," Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Christensen, C. M. and Raynor, M. E. (2003), "The innovator's solution: creating and sustaining successful growth," Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Narayanan, V. K., Yang, Y. and Zahra, S. A. (2009), "Corporate venturing and value creation: a review and proposed framework," Res Policy 38(1), pp. 58–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.08.015.

Wurzer, A. J., Grünewald, T. and Berres W. (2016), "Die 360° IP-Strategie," Franz Vahlen GmbH, Munich.

Gassmann, O., Bader, M.A. (2011), "Patentmanagement—Innovationen erfolgreich nutzen und schützen," Springer, Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York.

Weibel, B. (2013), "Strategisches IP Management— Aufgaben und Integration in die Wertschöpfungskette," in Schweizer IP Handbuch, Helbing Lichtenhahn, Basel.

[2] Ries, E. (2011), "The Lean Startup," Random House, Inc., New York.

Blank, S. and Dorf, B. (2012), "The Startup Owner's Manual," K&S Ranch Inc., Pescadero, CA.

Osterwalder A. and Pigneur Y. (2019), "Business Model Generation," John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

[3] Schwarz, S. and Kruspig, S, (2017), "Computerimplementierte Erfindungen—Patentschutz von Software," Carl Heymanns, Köln.

[4] Gackstatter, S., Lemaire A., Lingens, B., Böger, M. (2019): "Business Ecosystems," Roland Berger GmbH, Munich.