les Nouvelles August 2022 Article of the Month:

Build-To-Sell Powered By Intellectual Assets:

A High-Growth Technology Business Perspective

Founder and CEO, Globalator

San Diego, California USA

Abstract

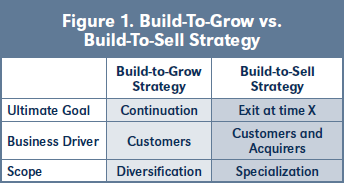

Owners of high-growth technology businesses should decide at an early stage whether they are developing their company for continuation as an independent organization (build-to-grow) or for an exit (build-to-sell). The choice of one pathway over the other has a huge impact on the strategic decisions made when building a successful business.

The three key intellectual assets—technology, brand, and operational excellence—are dominant value drivers for an exit deal in a build-to-sell process. Developing a sound portfolio of intellectual assets over many years before the exit will not only provide the business owners with an increased exit valuation, it will also give the company a sustainable competitive advantage in the event a planned exit does not take place or is delayed.

When a build-to-sell choice is made, a dedicated board function should have the prime responsibility for the salability of the business, allowing the CEO to remain focused on the growth of the business. Continuous management of the exit process years in advance and for some time after the exit transaction is crucial for ultimate exit success.

1. Introduction

Most owners of high-growth technology businesses will, at some point in their life, be faced with the decision to sell their company. There are numerous reasons for wanting such an exit. The biggest challenge is that when the possibility arises, the vast majority of business owners are not prepared for this milestone in their life as entrepreneurs. They are often driven by the process of an exit, instead of driving it proactively with a professionally managed build-to-sell strategy that optimizes the business for the best possible deal. As intellectual assets generally need years to be established, and are often the key value drivers for an exit deal, this calls for a process that starts many years before an intended sale. Moreover, it is also important to ensure management continuity for some time following the exit transaction. Business owners should decide early on whether they intend to follow a build-to-grow or a build-to-sell strategy and then develop their company accordingly.

2. Build-to-Grow vs. Build-to-Sell

Build-to-grow and build-to-sell are two fundamentally different strategies open to the business leader when building a company.

The ultimate goal when employing a build-to-grow strategy is to continue the business in perpetuity. On the other hand, a build-to-sell strategy has the clear goal of selling the business at a certain point in the future. Key strategic decisions are made with this goal in mind and differ if the time horizon is one to three years, three to five years, or five to ten years. For example, it would make no sense to invest in building a large new factory with a one-to three-year exit time horizon, since the construction work alone would take two years, and the potential purchasers may not even be interested in an additional manufacturing facility. Anything significantly below a 12-month time horizon tends to be a patch-to-sell approach with limited options for creating value.

When asked whether they would like to sell their company, many business owners reply with, “I am willing to sell if the right offer comes along.” However, from a marketing strategy perspective, this is a fundamentally flawed statement. No marketing expert would ever say that they will think about the customer only once their products or services are market-ready. Successful marketing starts with the customer in mind, way before the product or service offering has been finalized.

If a business in build-to-grow mode wants to succeed in selling its products or services, the sole business driver will be the customer’s needs. By contrast, a business following a build-to-sell strategy has two business drivers: first, the needs of customers who actually buy the products or services, and second, the needs of potential buyers of the company. Opting for build-to-sell therefore requires a business to cater to two different customer groups that are not necessarily aligned.

To secure continuation over a long period of time (often many generations) under a build-to-grow strategy, it is generally helpful to expand the scope and diversify into different markets. Some markets change direction more frequently than others. Market change is inevitable, however. Sometimes a whole industry might be endangered by unforeseeable external factors. A good example of this is the recent coronavirus crisis, during which the hotel industry was seriously impacted without prior warning. A company with some level of diversification would have been much better prepared to sustain such a crisis. However, with the sudden increased demand for toilet paper in many countries, who could have known that being in the toilet paper business would have been a good crisis hedging strategy for a hotel business? When opting for a build-to-sell strategy, on the other hand, it is better to focus on and adopt a specialization pathway as potential buyers are generally in the market for something very specific. As a rule, the more an acquisition target fits into a clearly defined box, the easier it is to find buyers who are prepared to pay a premium for it. Moreover, a specialized business is usually easier to integrate, since the new owner does not have to spend months or years disposing of add-on elements that were acquired but do not fit the acquirer’s strategy.

As described above and shown in Figure 1, opting for a build-to-grow versus a build-to-sell strategy has a significant impact on how the business is developed and what strategic decisions are made. When building a company, settling on a strategy and deciding when to transition to a build-to-sell strategy is key at an early stage. This does not mean that the strategy cannot be re-evaluated every year. However, it is better to have a clear understanding of where the journey is heading from the start. Hope is simply not a good business strategy.

2.1 Build-to-Grow Strategy

The most common reasons for adopting a build-to-sell strategy are:

Family Legacy

When the intention is to pass the business on from one generation to another within a family, the obvious strategy is build-to-grow. To be effective, this strategy needs to ensure a proper handover to the next leadership. Companies that are successful with a family legacy business generally have a well-defined process of how future CEOs develop their skills and abilities in non-affiliated companies. This ensures higher respect for the successor and offers an opportunity to bring a new way of thinking into the company from the outside.

Lifestyle Business Choice

For some reason, a lifestyle business often has a negative connotation in the management education realm as a business that is not pursuing maximum growth. However, there is nothing wrong with running a business with the primary goal of job satisfaction and providing the funding required for the owner’s lifestyle. It is a perfectly good choice and generally the route to follow when the owner employs a build-to-grow strategy, provided growth is actually desired. In addition, a lifestyle business does not necessarily mean a small company.

Going Public

While the strategy of developing a company to become a publicly listed entity through an IPO could be considered a separate strategy type (build-to-IPO), for the purpose of this article it is classified as a build-to-grow strategy rather than a build-to-sell strategy. Generally, the purpose of an IPO is to ensure the continuation of the business with the opportunity of getting easier access to funding for planned growth. When a company is primed for an IPO, one key preparation is establishing highly professional operation and management systems that are adequate for a listed entity.

2.2 Build-to-Sell Strategy

The most common reasons for adopting a build-to-sell strategy are:

Investor Requirement

High-growth technology businesses often have such significant capital requirements that bootstrapping (building a company without external equity financing) is not an option. Moreover, since debt funding is limited by the collateral that a business owner can put up, most high-growth businesses require equity funding. The majority of equity financing comes from funds with a limited lifetime (usually 10 years). Therefore, they need to cash in on their investment to realize a positive return on investment at some point. This means that equity funding generally comes with the requirement for a build-to-sell strategy and a time frame dictated by the remaining life of the fund providing the money.

Personal Risk Reduction

Sooner or later, many long-term business owners realize that their wealth is trapped in their company. At the same time, even the most successful businesses will fail at some point due to internal or external factors. At an all-hands meeting in November 2018, Jeff Bezos told his employees “I predict one day Amazon will fail. Amazon will go bankrupt... We have to try and delay that day for as long as possible.”1 With that realization, it is logical that many first-time business owners in particular will want to “cash in their chips.” Some will become serial entrepreneurs, starting one business after another. Others will simply retire, enjoy life and/or become angel investors. In general, selling a high-growth technology business is a positive, life-altering experience for entrepreneurs as it allows them to do what their investors do: diversify their risk.

Big Cash-Out

There are few ways of achieving a major cash-out event, besides inheritance (not everyone is born into a wealthy family), marriage (not everyone wants to look for a spouse with the right monetary background), and luck (the chances of winning the lottery are not considered to be very high). One opportunity is to become an entrepreneur and sell the business. Apart from either already having or developing the skills needed to be an entrepreneur, employing a proactive build-to-sell strategy from the very beginning can significantly increase the chances of a big cash-out event.

3. The Anatomy of a Successful Exit

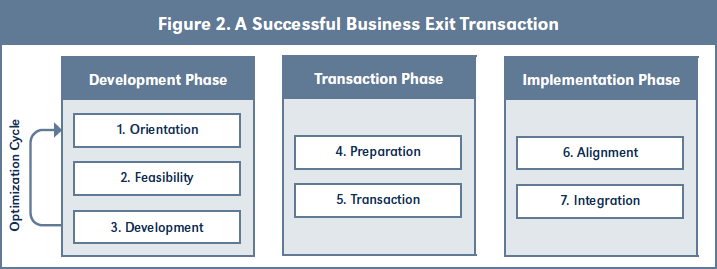

Most business owners make the mistake of treating the sale of their business as a situation to be tackled when the time is right. In many cases, however, some unforeseen event triggers the exit process. Such events include the proactive approach of a potentially interested party, the unexpected deterioration of the owner’s personal health due to stress, and the slowdown or even decline of business growth due to market changes. The problem with all these triggers is that they start forcing the unprepared owner into a short-term exit process. Investment bankers, M&A advisors, and business brokers jump to the rescue, start the transaction phase and try their best to close a deal. Nonetheless, their job is neither to develop a business nor to ensure its integration with the new owner, but simply to close the best possible deal under the given circumstances. A proactive build-to-sell process starting at least one year before a business is sold (the earlier, the better) and managed from within the company is the best insurance for business owners to optimize their value, retain control, and drive exit opportunities, instead of being driven by them. In reality, a successful exit transaction is not an event but a journey, where value is accumulated during the development phase, captured during the transaction phase, and secured during the implementation phase (see Figure 2).2

3.1. Development Phase

The first step when embarking on a build-to-sell strategy is understanding the expectations for the end of the journey through an orientation process. The owner has to define what they want to get out of the exit and what the expected timing is. For some owners, financial gain alone is key; others consider it vital that their employees and/or the established brand have a future after the business is sold. The personal exit timing might be determined by a certain age of the owner or by a targeted market position, achieved by the company to optimize the sales price. Expectations are as different as people and no two situations are alike. This becomes even more complicated if there is more than one owner, because all expectations need to be aligned first to define a solid build-to-sell strategy.

When the expectations for the exit are clear, a feasibility process submits these and major strategic decisions to a reality check. Feasibility discussions may already take place during the orientation phase and sometimes a negative feasibility check can bring the process back to this phase. One example is if the company decides to make one or more acquisitions to achieve a size that is attractive to potential buyers. It may be necessary to verify the availability of such targets and the funding of the acquisitions. A significant acquisition in a one- to three-year build-to-sell process might not be feasible but could realistically be managed in a time-frame of three to five years.

Once a strategy has been determined and evaluated through a feasibility process, the actual development process can begin. This is where the real value is added to the business. It is also the point where a list of potential buyers is drawn up and their needs analyzed to understand what kind of company would attract enough potential buyers who fulfill the expectations of the owner(s). Alliances might be formed with potential buyers to get on their radar. Licensing deals might be made to strengthen the intellectual property portfolio or close gaps in the freedom-to-operate status quo. Spin-offs might be established to create the possibility of serial exits or enable the owner to sell one part of the business and keep another. Acquisitions might be made to enhance the growth of the company. Business units that do not contribute to the value of the business from a buyer’s perspective might be discontinued or sold. In fact, this whole development phase is where the ultimate value is either created or lost. It is also when the intellectual asset portfolio (see Section 4 below) needs to be established since all key intellectual assets (technology, brand, and operational excellence) take years to build. Once the development process begins, a regular optimization cycle should be maintained to re-evaluate whether what was determined in the orientation process is still valid, and whether the development strategy needs adapting.

3.2. Transaction Phase

A business with a proactive build-to-sell process in place is not only able to start the transaction phase when the time is right, it is also well prepared to deal with unexpected events that might trigger an exit. The starting point of this phase is usually the development of an information memorandum, which is a sales document that allows potential buyers to declare their interest in an acquisition. The preparation process also includes a more detailed analysis of potential acquirers. While a well-prepared business has already maintained a list of potential buyers throughout the development phase, this is the time to expand that list and possibly disqualify potential contenders. It is also the time to decide whether not only strategic buyers but also private equity funds might be considered as potential acquirers. Private equity funds can be a great option for smaller businesses that still need to be built further for a successful sale, but where the owner already wants to cash out. In many cases, these funds prefer to buy only a portion of the business, provide some needed growth capital, and keep the owner on board until a full exit takes place at a later date.

Once all preparations are complete, the actual transaction process can begin. One important decision is whether to adopt a broad or a narrow approach. A broad approach has the advantage that every potential buyer is invited to a structured process. The disadvantage of the broad approach is that the whole industry will find out that the company is for sale. This can limit the continuation of the business should the exit process be stopped for any reason and the company continue as a standalone entity. The reason for this is that players in the industry may well be reluctant to work with a business that might be sold in the next attempt. The narrow approach has the advantage that knowledge of an intended sale can be limited to a few selected companies, avoiding backlashes if the business continues without an exit. The downside is that the limitation to fewer targets might miss a potential buyer for the best possible deal. In the end, there are many shades between approaching hundreds of companies versus only one; making a conscious decision, based on a clear analysis of advantages and disadvantages in each particular case, is key.

3.3. Implementation Phase

Once the deal is signed and the transaction concluded, the implementation phase can begin. Unless the acquisition was made by the buyer to operate the business without any significant changes or to close down the acquired entity, this is where things often start to go wrong. Integrating a business is an art in itself. According to an article in Harvard Business Review, 70 to 90 percent of acquisitions are abysmal failures.3 The main reason why successful implementation matters, not only to the buyers but also to the sellers, is that earnout payments (see Section 4) can represent a significant portion of a deal and depend on the success during or after the implementation phase. Another “soft factor” is that most owners want to see the business continue, and many find it important to secure the future of their trusted employees. A solid build-to-sell process that was established years before the transaction phase and ensures the building of a business ready for integration with a potential acquirer will make the acquisition more attractive for the buyer and create a win-win situation for both seller and buyer. For this to happen, a business embarking on a build-to-sell strategy should establish an in-house function at the board level that has the responsibility for overseeing the development phase towards an exit, the transaction phase, and that continues to stay involved during the initial alignment process, ensuring a sustainable success of the transaction.

When the alignment process has determined how the future joint business will work, the integration process kicks in. This is where the build-to-sell board function starts fading out to ensure the handover to the new business owner runs smoothly. If the process was managed correctly, the seller will not only receive the adjusted purchase price but also most of the escrow holdback and the maximum achievable earnout payment (see Section 4 and Figure 3). Generally the seller’s goal is the perfect deal that ensures the best possible financial return for the seller, a business performing above expectations for the buyer, and a secure future for the employees of the company. While it will not always work perfectly, choosing a proactive build-to-sell process favors the best possible outcome.

4. The Role of Intellectual Assets for the

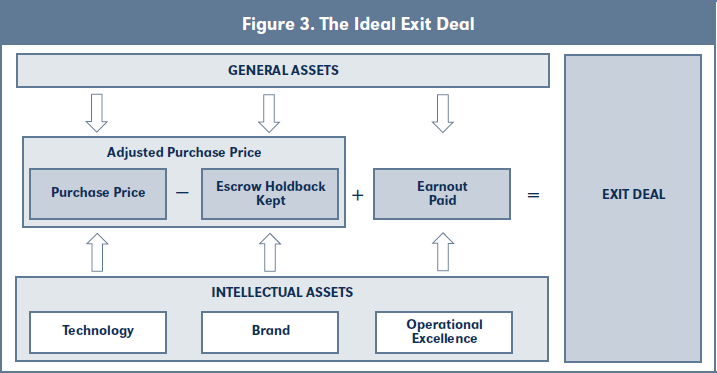

Exit Deal

Intellectual assets are of fundamental importance for a successful exit deal. Since they cannot be established at short notice prior to a pending exit, the process of building a sound intellectual asset portfolio must begin many years beforehand, during the development phase (see Section 3). As mentioned above, the ideal exit deal ensures that, in addition to the initial payment at closing, the buyer releases the majority of the escrow holdback and the seller receives the maximum possible earnout payment from the performance of the business under the new ownership (see Figure 3).

For the purpose of this article, the purchase price is the overall price that the buyer is willing to pay to acquire the business. In case of an equity deal, the buyer receives full ownership in the seller’s company (provided they buy 100 percent of the business, although in some cases the buyer might only acquire a certain percentage). In the event of an asset deal, the buyer purchases only specific assets of the business.

As a rule, however, the purchase price is not the amount that the seller will receive once the deal is closed. In most cases, the buyer will require the seller to provide binding promises (contractually fixed under representations, warranties, and indemnifications) that certain assumptions about the business are correct. One simple example is that the inventory actually represents the value claimed by the seller. To secure these promises, the buyer will ask that a certain portion of the purchase price (depending on the industry and the risks perceived by the buyer) be deposited in an escrow account as an escrow holdback, managed by an escrow agent. This escrow holdback is subsequently released either to the seller or to the buyer, based on contractually defined terms and timelines. The initial price paid is thus the adjusted purchase price, calculated as the agreed purchase price minus the escrow holdback deposited in an escrow account, ownership of which is only determined throughout the escrow period.

Companies that have been set up for high performance under new ownership through a solid build-to-sell process and supported by a strong intellectual asset portfolio have the potential to benefit from an additional earnout agreement. An earnout provides supplementary payments over and above the agreed purchase price for achieving defined performance criteria. In most cases, these performance criteria are based on sales performance. However, along with countless other options, they could also include certain milestones in a product development process. While the escrow holdback has the potential to reduce the agreed purchase price, the earnout paid adds to it. The tricky part about receiving earnouts is that, by this point, control over the performance has shifted to the new owner, and any success depends not only on the right preparation on the part of the seller, but also on the cooperation of the buyer. While certain requirements may be put in place by the seller to enable earnout performance, the main driver here is business logic combined with management support from the seller’s team.

The following example from the life sciences industry illustrates the possible impact of escrow holdback and earnout on the actual amount received by the seller (parameters depend on the individual situation and the industry). With a purchase price of $50 million, plus a 20 percent escrow holdback and a $20 million earnout, the difference between a worst-case scenario (all the escrow holdback is kept by the buyer and no earnout is paid=$40 million exit deal value) and a best-case scenario (the entire escrow holdback is released to the seller and the full earnout is achieved = $70 million) would be $30 million. This translates to a 75 percent higher overall exit price if the business was well prepared in a build-to-sell process and the implementation phase went according to plan. Intellectual assets are major contributors to and increase the likelihood of a higher purchase price in the first place and a higher overall exit deal.4

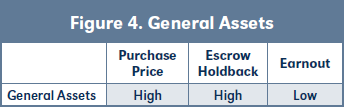

4.1. Impact of General Assets

General assets typically include customers (expressed in revenue), cost structure (expressed in gross margin and profitability), established contracts, equipment, inventory, work in progress and team members. As the foundation of any business valuation, they have a substantial impact on the purchase price because they are relatively easy for the acquirer to evaluate in a due diligence process. Since an escrow agreement needs clear trigger points to determine whether the seller or the buyer receives the retained funds, general assets also have a huge impact on the escrow holdback. While general assets may serve as the foundation of an earnout (e.g., equipment with significant spare capacity enables the sales team to sell more products), their impact on it is usually low. See Figure 4.

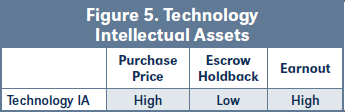

4.2. Impact of Technology Intellectual Assets

Strong technology intellectual assets (IA) combine the technology intellectual property mainly secured by patents and trade secrets with the know-how of the team.

For a company with a strong technology portfolio, the impact of technology on the purchase price can be significant, especially when it gives the business a sustainable competitive advantage. For example, patent-protected technology with a clear enforcement and freedom-to-operate position that allows the company to exclude competitors for a relevant period of time increases value as the current performance and growth pattern is more likely to continue.

The impact of technology on the escrow holdback tends to be low, as it is relatively difficult to find trigger points that would provide an escrow release payment to one of the parties. One example in which technology might have an impact on the escrow holdback is a pending patent lawsuit that could threaten a business’ technology foundation where winning or losing patent litigation could determine the payout of an earmarked holdback.

From an earnout perspective, technology can have a high impact on an agreed earnout. This is especially true if, for example, the company owns platform technology that has been tried and tested in only one market segment, but could be used to access one or several other markets. It could be part of an earnout payment based on future sales in those new markets, provided the buyer agrees to enter those markets shortly after the deal is completed. See Figure 5.

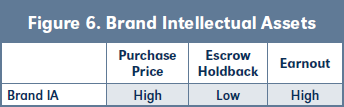

4.3. Impact of Brand Intellectual Assets

Strong brand intellectual assets (IA) combine the brand’s intellectual property secured by trademarks with the ownership of customer mindshare, where individuals associate the brand with certain attributes.

A strong brand almost always has a powerful impact on the purchase price although the brand value is generally higher in business-to-consumer than in business-to-business focused companies. This is interesting as, in most cases, the seller’s brand will be replaced with the buyer’s brand. However, having a strong brand, where the task is not finding new customers who have positive associations with it but transferring existing positive associations to a new brand in a controlled step-by-step process, is still of great value to a buyer.

Since a brand is generally easy to assess in a due diligence process, the impact of the brand on the escrow holdback is almost always low. One situation in which an escrow holdback might be impacted by the brand is when the acquired company does not own a registered trademark with an uncontested status and there is reason to believe that the brand might actually violate existing trademark rights of another company.

Earnouts are usually based on future sales performance. Since great sales performance builds on a strong brand that has been established over many years, the impact of the brand on an earnout is generally high. Moreover, the value increases if the buyer can use the seller’s brand to expand the product portfolio quickly by targeting the seller’s existing customers with their own products. See Figure 6.

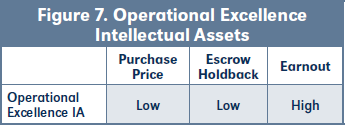

4.4. Impact of Operational Excellence Intellectual Assets

Strong operational excellence intellectual assets (IA) allow a company to consistently outperform others and combine the operational excellence intellectual property secured by the operational systems with a culture that enables operational excellence.

Interestingly enough, operational excellence rarely has a direct impact on the purchase price from a valuation perspective. The reason is that it is very difficult to prove the actual level of operational excellence in a company in a common due diligence process. Nevertheless, since operational excellence serves a company in a build-to-sell process during the development phase (see Section 3) and can ensure high sales growth, a high gross margin, and fast product time-to-market, it has a significant intrinsic value affecting the purchase price.

Generally operational excellence does not have a major impact on the escrow holdback. Although some buyers might try to link the potential loss of key employees to an escrow trigger point, the truth is that this issue is better served with a special tie-in contract, retaining key employees for a certain period of time with defined bonus payments. Moreover, it would be very difficult to define escrow payment release trigger points for underperformance in terms of operational excellence.

Operational excellence really shines when it comes to the earnout. A business developed for a sale through a solid build-to-sell process will have established at least a certain level of operational excellence and it is easier to be integrated into the company structure of the buyer. Consequently, when the former CEO steps down and a new CEO takes over, a business with operational excellence will continue to perform: this performance secures the earnout payments. However, it is important that the seller still has someone in place to manage the transition carefully and ensure a smooth handover. This role is ideally performed by a person or a team that has been managing the build-to-sell process since the development phase and is therefore very familiar with the company. See Figure 7.

5. Conclusion

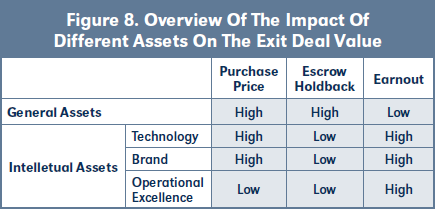

Intellectual assets are a significant contributor to the exit deal value and need to be established over many years during the development phase of a business (see Figure 8 for an overview of the impact of different assets on the exit deal value).

The secret to the success of an optimized exit is understanding that different assets have a different impact on the three key factors of an exit deal: purchase price, escrow holdback, and earnout. General assets have the highest impact on the adjusted purchase price (the purchase price minus the escrow holdback deposited in an escrow account) and very little impact on an earnout. Technology and brand intellectual assets generally have a high impact on the purchase price and very limited impact on the escrow holdback but are the key drivers for an earnout. Operational excellence is an inconsequential outlier in the intellectual asset class as its impact on the purchase price is more intrinsic. On the other hand, it is usually the most important driver for earnouts.

Therefore, an owner of a high-growth technology business should ensure that a proactive build-to-sell process is initiated at an early stage, developing a solid portfolio of intellectual assets to secure the value of the business. In the event an exit does not materialize for any reason, these intellectual assets will continue to be the backbone of the sustainable competitive advantage that the company has built. In any case, a business cannot go wrong with a strong intellectual asset portfolio.

Furthermore, if a business owner opts for a build-to-sell strategy, they should establish a build-to-sell function at board level in their company that is tasked with guiding the company from the development phase through the transaction phase and into the implementation phase. The business owner should focus on managing day-to-day operations with a steady eye on the customers, while the build-to-sell function’s prime focus is the company’s salability. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=4099758

Author

Juergen Graner, member of the HTB Task Force at EPO and the HGE Task Force at LESI.

Acknowledgement

Reviewer and editorial support was provided by Patrick Monroe, Yasmin Law, Adéla Dvoráková, Ilja Rudyk and Thomas Bereuter.

- See article on CNBC online on 15 Nov. 2018—https:// www.cnbc.com/2018/11/15/bezos-tells-employees-one-day-amazon-will-fail-and-to-stay-hungry.html

- See also the article, “People as Enablers,” co-authored by Juergen Graner, les Nouvelles, June 2020.

- See article “M&A: The One Thing You Need to Get Right.” by Roger L. Martin, Harvard Business Review, June 2016

- For more information on intellectual assets as value drivers for strategic transactions, see also the article, “Transactions Powered by Intellectual Assets,” by Juergen Graner, les Nouvelles, June 2020.