les Nouvelles December 2020 Article of the Month:

Transactions Powered By Intellectual Assets:

A Decision-Maker's Perspective

Globalator LLC

CEO

San Diego, California, U.S.A.

Abstract

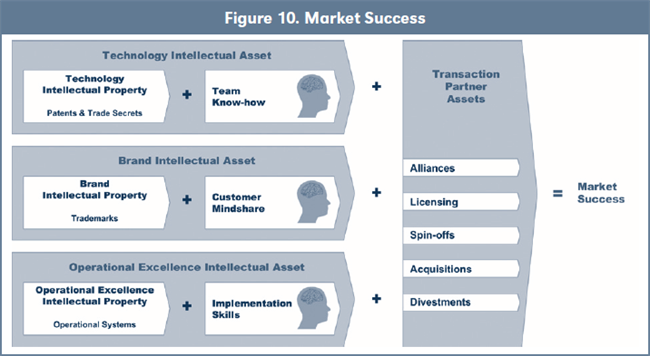

Decision-makers in technology companies who embark on a high-growth strategy for their company will likely engage in one or more of the following five strategic transaction types to optimize shareholder value: alliances, licensing, spin-offs, acquisitions and divestments.

Full utilization of key intellectual assets (technology, brand and operational excellence) as core drivers for strategic transactions ensures best results when executed properly. The common success enabler for any intellectual asset is the human factor. Technology intellectual property based on patents and trade secrets needs to be enabled with team know-how. Brand intellectual property based on trademarks needs to be enabled with customer mindshare. Operational excellence intellectual property based on operational systems needs to be enabled with implementation skills.

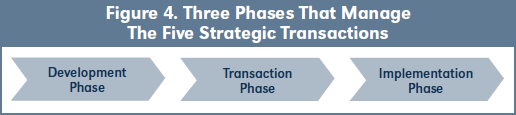

Moreover, in order to make strategic transactions successful, decision-makers need to implement a continuous management process throughout all transaction phases. Solid preparation during the initial development phase and the proper management of the final implementation phase after a deal has been signed secure the ultimate value of a transaction.

1. Introduction

When business decision-makers enter into strategic transactions, such as alliances, licensing, spin-offs, acquisitions and divestments, the overall goal is to generate the highest value possible. Any transaction is done based on a fundamental asset or a group of assets controlled by the source company. The goal of a strategic transaction is to increase the intrinsic financial value by adding a strategic value component, which comes from combining the asset package from the source company with an asset package controlled by the transaction partner. For example, a company that has developed a new product (source asset package) would see a tremendous value increase by combining this with another company that has an established global market access to the intended customer base (transaction partner asset package).

In most strategic transactions the ultimate drivers of strategic value are intellectual assets. The key for creating value with intellectual assets is to combine intellectual property with the human factor, as this article explores in more detail.

2. Key Intellectual Assets

The following three intellectual assets have been proven to be the ultimate value generators in business practice: technology intellectual assets, brand intellectual assets and operational excellence intellectual assets.

2.1 Technology Intellectual Assets

Especially for technology based companies, it is very important to generate intellectual property rights that are owned by the entity. Therefore, a lot of money is spent on the creation and protection of patents, trade secrets and related intellectual properties, which provide the foundation for a technology intellectual asset. However, unless an organization is able to create an environment where its engineers and scientists can flourish and are motivated to continuously invent and create, the underlying technology will either not reach its full potential or eventually become obsolete (Figure 1 shows that technology intellectual property only becomes a technology intellectual asset if combined with team know-how). Once the complexity of a transaction partner is added, in many cases, the challenge to manage ongoing innovation increases exponentially.

2.2 Brand Intellectual Assets

The brand is almost always an important factor in any type of company. Most decision makers understand that in order for a brand to be strong, it needs to be protected through a trademark in the jurisdictions where business is conducted. Similar to a technology intellectual property, the brand intellectual property needs to be combined with the human factor in order to become a brand intellectual asset. Different from technology though, the human factor is not within the control of the company. A brand is basically the ownership of customer mindshare, which is a manifestation within the customer's mind, created through their own experience with associated products and/or services, combined with information absorbed from others and from perceived marketing messages (Figure 2 shows that brand intellectual property only becomes a brand intellectual asset if combined with customer mindshare). A brand intellectual asset is very fragile since it takes a long time to build, but, especially in today's interconnected world, it can easily be destroyed. The association of the brand of the source company with the brand of the target company after a transaction needs to be managed proactively, since it has an important impact on both brand intellectual assets.

2.3 Operational Excellence Intellectual Assets

One of the most undervalued intellectual assets for transaction value generation is operational excellence. A business has operational excellence if it is able to do something better and/or more efficiently than others on a continuous basis, with the ability to adjust to changing environments. This could be related to any part of the value chain within the organization. Examples include a company that may have the best way to manufacture certain products, the best way to develop new products or the best way to provide certain services. The ability to have operational excellence in a company as an intellectual asset is strongly linked to its employees and the culture that has been created within. Many businesses write down the ways operational processes are conducted in manuals and standard operating procedures to create operational systems that form the intellectual property base. However, the real value of those systems actually comes from the implementation skills embedded in the team (Figure 3 shows that operational excellence intellectual property only becomes an operational excellence intellectual asset if combined with the implementation skills of the team). Generally, those team skills are enabled by the culture of the organization. They are difficult to transfer and need to be managed diligently after a transaction has been completed, since they may be lost if certain key employees leave.

3. Transactions Powered by Intellectual Assets Done Right

The three key intellectual assets explored in the previous section can be used to power the five most important strategic transactions: alliances, licensing, spin-offs, acquisitions and divestments. When engaging in any of these transactions, the following three phases have to be managed diligently, with a special focus on seamless management continuity from one phase to the next (see Figure 4).

During the initial development phase, the source business is developing the assets that are required for a potential transaction. Generally, the highest value generation takes place during the development phase. Unfortunately most companies handle transactions in an opportunistic manner, without the proper strategic focus, planning and development before they enter into a transaction.

The actual transaction phase is there to properly prepare the deal and enter into a legal contract. Although this is usually the phase with the lowest value generation, a lot can be lost if parties are not able to agree to the right terms and fail to consider the actual implementation phase in those terms. While it is highly recommended to engage a lawyer to help with the legal aspects, the general consensus amongst decision makers is not having lawyers drive the deal. As a general rule, whoever will lead the implementation phase should also lead the transaction phase.

Once the deal is signed, the transaction enters the implementation phase where both parties will need to "live with the deal" that they have just made. This is normally the phase with the second highest value generation potential. Unfortunately most companies do not have a continuous management function for the deal in place from the development phase all the way into the implementation phase, and therefore often struggle with the implementation of their transaction.

3.1 Alliances Driven by Intellectual Assets

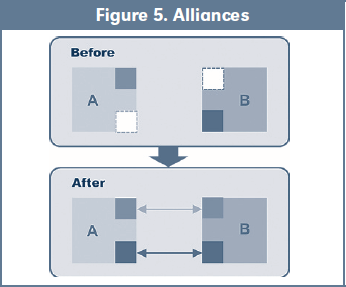

An alliance, also often called a strategic partnership, is formed if each party has assets that complement each other. Both parties commit resources for the duration of the alliance and each party remains independent (Figure 5 shows that both the source party A, as well as the target party B, have a gap that can be filled by the other party. Once the transaction phase has completed, both parties are able to fill the gap and enter into a longer-term relationship). There are many different types of alliances (e.g., R&D, manufacturing, procurement, servicing, co-branding, co-promotion, referrals, sustainability). This article elaborates on an outbound distribution alliance as an example, which is something almost any company that expands internationally will embark on at some point in its life. For an outbound distribution alliance, the most important intellectual asset is usually the brand, provided that the products and/or services are to be distributed in the new target territory under the source company's brand. The target alliance partner has the responsibility to build and expand the brand in the new market.

The key challenge in an outbound distribution alliance is that there is often an inherent misalignment of incentives between both parties that neither party is addressing with the other proactively. The distribution partner generally is only motivated for "good enough" performance. If the performance is bad, then the distribution partner knows that it will be replaced by someone else. If the performance is excellent on the other hand, then the distribution partner knows that it may be replaced by the source party establishing its own footprint in the target market. The most viable solution is to tackle this problem head on, communicating with the alliance partner already in the development phase about that issue and coming to a joint solution that works for both sides. If the intent is to eventually take over the new target market, the source party could offer the distribution partner a more significant financial upside tied to the success after the handover or find some other alignment solution. This openness and understanding of the target party's concerns, combined with a rather proactive management of the relationship during the implementation phase once the agreement has been signed, is very important to not only grow the source company's brand intellectual asset, but also to protect it. In today's globally connected world, any damage that a potential distribution partner might cause to the source party brand in the new market could have a detrimental impact on other territories. Accordingly, decision-makers need to make sure to manage the process well.

3.2 Licensing Driven by Intellectual Assets

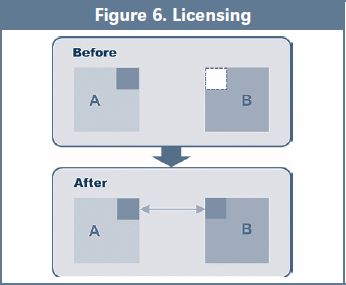

A licensing transaction is usually formed if at least one party has a protected brand or technology asset that can be useful to the other party. The target party generally intends to commit significant resources for the duration of the license, and each party remains independent (Figure 6 shows that the target party B has a gap that can be filled by the other source party A. Once the transaction phase has completed, party B is able to fill the gap, and both parties continue a longer term relationship with each other). Such a licensing transaction may be incoming (in-licensing), outgoing (out-licensing—see Figure 6) or bi-directional (cross-licensing).

If the licensing transaction is based on a brand, the most important intellectual asset is the brand, which hopefully has been protected through trademark registrations in the target regions. Such brand licensing transactions are often entered into to capture new markets with new product categories building on a certain, already well-established brand positioning in the target market.

The key challenge in a licensing transaction driven by brand intellectual assets is closely related to the challenges faced by an outbound distribution alliance (see previous section). Allowing another party to utilize a company's brand seems to be an easy way to make more money without increasing operational challenges. However, if the transaction partner does not manage the customer mindshare carefully during the implementation phase, any backlash on the brand in the transaction partners' hands could have a dramatic impact on the brand in the source market.

If the licensing transaction is based on a technology, the most important intellectual asset is the technology, which hopefully has been protected by patents, trade secrets and related intellectual properties. Generally, a technology licensing relationship is entered into if the target party has the ability to use the technology in an area that the source party cannot execute in to the fullest possible extent.

The key challenge in a licensing transaction driven by technology intellectual assets is often not so much the transfer of the technology and the related know-how, but ensuring that the transaction partner will really do their very best during the implementation phase, turning that technology into something that can and will be sold in the market at a peak performance level. While a solid, well-negotiated contract during the transaction phase might provide the source party with some steering elements (e.g., minimum royalties) to ensure market success, the only true success formula is a functioning and stable relationship with the partner for the entire life of the licensing relationship. It is therefore advisable to take sufficient time during the development phase in selecting the right partners and early on establish a long-term relationship that is built to last.

3.3 Spin-Offs Driven by Intellectual Assets

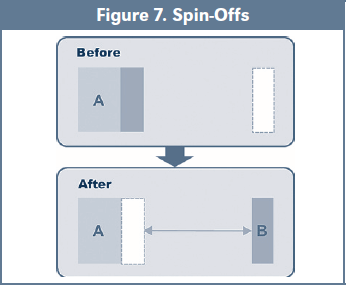

A spin-off is usually done if either the potential of a certain technology intellectual asset could benefit from a separate entity (spin-off venture) or if a business unit no longer fits the current business strategy and could evolve better as a separate entity (unit spin-off). A spin-off venture is mostly based on technology intellectual property, whereas a unit spin-off generally includes a whole team. In either case, a separate entity is created, but a strategic relationship between the two entities remains (Figure 7 shows that source party A has an asset that could be suitable for a spin-off. Once the transaction phase has completed, a new target party B is created, and both parties continue a longer term strategic relationship with each other). In many cases spin-offs are created together with one or more other partners to form a joint venture.

When a technology-driven spin-off venture is created, usually a new team is formed around some core technology intellectual asset that has either been transferred or licensed to the spin-off (in the latter case, this would be a combination of a licensing and a spin-off-transaction). Often separate funding is raised for such an endeavor, and the new team in the new entity starts building its own technology intellectual assets and its own operational excellence intellectual assets around the technology provided.

The key challenge in spin-off ventures is what to do when the spin-off team finds out after the transaction has closed that additional technological capabilities are needed from the source business. This is especially difficult if there is a joint venture partner that has provided the technology foundation for the new entity and now sees a chance for renegotiating the transaction terms. In order to avoid such a scenario, significant effort needs to be put into the development phase, creating a very detailed and realistic operational business plan (not to be confused with a sales-pitch-driven business plan for investors) ahead of time. It would also be advisable to negotiate a long-term alliance relationship between the source company and the spin-off to be able to close any potential future technology gaps early on with clearly defined parameters. Although as a sole owner, this problem is likely easier to resolve, it is still advisable to be just as careful in the development phase as if a joint venture partner was part of the transaction; otherwise any change in plans at a later point might still result in an unexpected interruption of the source business as well as in the spin-off.

When a unit spin-off is created, a whole existing team from the source business serves as the foundation for the new entity, generally combined with some technology intellectual asset. By definition, the source party loses some of its technological capabilities and sometimes also certain commercial capabilities. Also in this case, the transaction might be accompanied by including external investors. A unit spin-off is not to be confused with a management buy-out (MBO) of a part of the business. An MBO would be considered a divestment from the selling party perspective, since generally no strategic relationship remains between the two transaction parties after the transaction.

The key challenge in unit spin-offs is often the exact opposite of the one in spin-off ventures. In this case the source business might discover at some later stage that certain technological or commercial capabilities that are needed have been lost to the spin-off. This gets very tricky in the case of a joint venture, where one source business joint venture partner suddenly asks the spin-off to spend valuable resources to provide help. It also becomes a problem with investors that are very unlikely to support slowing down the spin-off to help the source party. The solution is the very same as with spin-off ventures: ensuring a very thorough development phase with the establishment of a detailed and realistic operational business plan.

3.4 Acquisitions Driven by Intellectual Assets

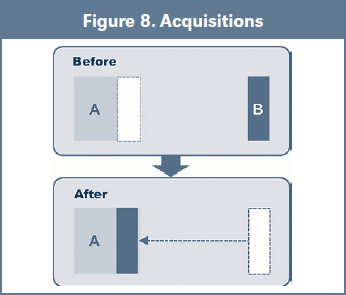

An acquisition happens if a selling party is interested in monetizing its entire business (equity deal) or certain assets (asset deal), and a buying party has an interest in acquiring those. The buying party takes ownership of the business or the assets, and the seller generally ceases to exist (Figure 8 shows that buying party A has a gap that can be filled by the selling party B. Once the transaction has completed, party B no longer exists). Also, a management buy-out or a management buy-in would be considered a special kind of acquisition from the buying party perspective, since they also result in a change of ownership, although in this case the complexity of merging two entities does not apply. While in some cases an acquisition transaction might be referred to as a merger with the intention to communicate an equality aspect, this usually is only lip service and does not reflect reality, since one party generally has the lead.

Depending on the target company, an acquisition can be brand-driven, technology-driven, operational-excellence-driven or a combination thereof. Generally, technology driven and operational excellence driven acquisitions are much more difficult to get right than brand driven acquisitions.

In a brand-driven acquisition, where the key intellectual asset is the brand, the focus during the development and transaction phase is to understand how the brand was built and how it can be stretched or expanded. The advantage is that, since a brand intellectual asset generally does not rely on the internal team of an entity, but on existing customer mindshare, the implementation phase is less dependent on the employees staying on board and being motivated to support the new owners. It gets slightly more complicated when the owner is personally part of the brand. If that is the case, the owner needs to stay on board for a considerable time to allow for a transition period, where the brand can transfer to become disassociated from the owner.

The key challenge for brand-driven acquisitions is for the new marketing team to have a clear brand strategy and implementation plan early on during the implementation phase. Fortunately, the buying party generally has some time to get this right.

A technology-driven acquisition or an operational-excellence-driven acquisition is much more fragile from a management perspective. A technology intellectual asset usually consists of patent-protected technology paired with the scientific and technical know-how from the team on the execution side. Similarly, operational excellence intellectual assets consist of hopefully well-documented operational systems coupled with the implementation skills of the team. Unless the technology is acquired simply to establish a freedom to operate position, and the buyer already has all the required capabilities in house, the focus here is on securing and motivating those key employees that provide the buyer with a continuous flow of innovation and consistent operational excellence.

The key challenge in technology-driven acquisitions is that the "human factor" is difficult to judge during the transaction phase, since it is almost impossible to get access to the full scientific or engineering team in a setting where their motivation and capabilities can really be judged within a conventional due diligence process. Therefore, the focus has to be on the implementation phase, during which one of the key tasks is to secure and motivate that scientific and technical team from the very beginning. Once traction with the team is lost in the process, there is a high risk of losing some of the best scientists and engineers. In the high-tech field, many companies intend to acquire capabilities (and often also pay a premium for that) but end up having purchased merely products.

The key challenge in operational-excellence-driven acquisitions is very similar to the one with technology-driven ones. One difference here though is that the goal is not to ensure a continuous flow of innovation but rather to continue the status quo of that operational excellence. Since operational excellence is strongly influenced by the culture of a company, it is very difficult to transfer that to another entity during the implementation phase (especially in a different country).

3.5 Divestments Driven by Intellectual Assets

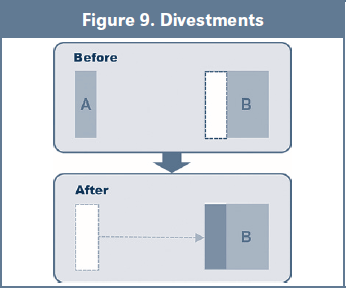

A divestment, also considered an exit, is essentially the other side of an acquisition. Everything mentioned above for acquisitions still holds true, but in this case the source business is on the other side of the transaction (Figure 8 shows that buying party B has a gap that can be filled by the selling party A. Once the transaction phase has completed, party A no longer exists). An exit does not necessarily mean that the entire business is sold. In some cases a partial exit might be desired, where the seller only sells a certain business unit (similar to a unit spin-off, with the difference being that no continuous strategic relationship remains with the sold entity) or certain assets. Moreover, several deals might be structured around a platform technology where different parts of a selling entity might be able to serve distinctly different markets with different products, in which case, a number of serial exits could be completed over time.

Generally, the biggest mistake owners make in selling their business is to consider it an end in itself during the development phase. It may be somehow counter-intuitive to consider a full divestment of a company a growth strategy, especially when it is driven by intellectual assets. However, this is exactly what is needed in order to create the ultimate value for the owners of the selling party.

Most owners are torn and believe that there is a trade off between the highest possible sales price of a business and the future of their employees. However, especially for technology businesses, this does not have to be the case if the business is built around strong operational excellence and technology intellectual assets. With a well-executed long-term build-to-sell strategy, starting at least two to three years before the intended sale, the focus is on how the potential future buyer of the business will be able to utilize the underlying assets in a synergistic or symbiotic way. If the key assets are based only on technology intellectual property without the team know-how (see Figure 1), then there is no additional strategic value for a potential buyer to keep the team in place, and the future value is limited. As described earlier in this article, an intellectual technology asset consists of intellectual property paired with people that can execute and build on it to create even more innovation in the future. If that is combined as well with operational excellence, which has been established in a way that someone else can also execute on, then the seller will not only reap the ultimate exit value, but also be in a good position to secure the future of their employees. So actually securing the future of the employees in a business to be sold can increase the exit value significantly. This does not always work, but there is no downside in trying to make money from securing the future of employees—a real win-win situation.

4. Conclusion

Most strategic transactions, no matter if they are alliances, licensing, spin-offs, acquisitions or divestments, create the best possible value if decision makers use key intellectual assets (technology, brand, and/or operational excellence) as the core drivers for value generation. Ensuring management continuity from the development phase all the way to the implementation phase is one of the key success factors.

Successful decision makers understand that intellectual property rights, such as patents, trade secrets, trademarks and operational systems, serve as qualifiers, without which a company will not even be able to participate in ultimate value generation from strategic transactions. However, the actual order winner that ensures long-term success is the human factor that needs to be in sync with the intellectual property. The level of market success depends on the people within an organization (team know-how, implementation skills) or outside in the marketplace (customer mindshare), combined with assets from the transaction partner (see Figure 10). Unfortunately in today's business reality, transaction management focuses too much on pure financial valuation, underestimating the people factor. This does not mean that valuations are not important, but the difference between a worst-case scenario, base-case scenario and best-case scenario is in the people. People make the numbers and not the other way around, which is especially true for transactions powered by intellectual assets. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN):

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3582891.